錬金術師にとって、主に贖いを必要としているのは人間ではなく、失われて眠っている神です。彼の注意は、神の恵みによる彼自身の救いに向けられているのではなく、物質の闇からの神の解放に向けられています。

For the alchemist the one primarily in need of redemption is not man, but the deity who is lost and sleeping in matter. His attention is not directed to his own salvation through God's grace, but to the liberation of God from the darkness of matter.

"錬金術師にとって、主に救済を必要としているのは人間ではなく、物質の中に迷い眠っている神である。"

"司祭は変換をもたらす聖別の言葉を発音することで、パンとワインを被造物としての要素的な不完全さから救済するのです。この考え方は全くキリスト教的ではなく、錬金術的である。カトリックがキリストの効果的な現存を強調するのに対し、錬金術は物質の運命と顕在的な救済に関心がある。囚われの身となった物質は、「神の子」という形で現れます。

錬金術師にとって、主に救済を必要としているのは人間ではなく、物質の中に迷い込んで眠っている神である。

錬金術師は、不完全な肉体やベースとなる金属、「病んだ」金属などと同様に、万能薬、medicina catholicaとして、変化した物質から自分自身に何らかの利益がもたらされることを二次的に期待しているに過ぎません。

彼の関心は、神の恩寵による自分の救済ではなく、物質の闇からの神の解放に向けられている。

この奇跡的な仕事に身を投じることで、彼はその救いの効果から恩恵を受けるが、それは付随的なものに過ぎない。彼は救いを必要としている者として作業に取り組むことができるが、彼は自分の救いが作業の成功に、つまり神の魂を解放できるかどうかにかかっていることを知っている。

そのために、彼は瞑想、断食、祈りを必要とし、さらに、彼の(パレドロス)聖霊としての聖霊の助けを必要とします。

救済されなければならないのは人間ではなく物質であるため、変容の中で姿を現す霊は「人の子」ではなく、クンラートが非常に適切に表現しているように、「大宇宙の子」である。

したがって、変身して出てくるのはキリストではなく、「石」と名付けられた不可解な物質的存在であり、体、アニマ、精神、超自然的な力を持っていることとは別に、最も逆説的な性質を示しているのである。

錬金術による変身の象徴を、ミサのパロディとして説明したくなるかもしれないが、ミサは異教徒のものであり、ミサよりもはるかに古いものではない。

神聖な秘密を秘めた物質は、人間の体を含めてどこにでもある。それは求めれば手に入るし、どこにでも、たとえ最も嫌な汚物の中にでも見つけることができる。

このような状況では、役職はもはや儀式的な儀式ではなく、神自身がキリストの例を通して人類に成し遂げた救済の同じ仕事であり、神の芸術であるdonum spiritus sancti(聖霊の賜物)を受け取った哲学者は、今や自分自身の個人的な作品として認識している。

錬金術師たちは、この点を強調しています。"他人の精神を利用して、雇われた人に仕事をさせる者は、真実からかけ離れた結果を見ることになり、逆に、実験室の助手として他人にサービスを提供する者は、決して女王の神秘に入ることはできない。"

また、カバシラスの言葉を引用することもできます。"王が神に贈り物をするときには、自分でそれを負担し、他人に負担させることを許さないように。"

錬金術師は、実際のところ、決められた独り者であり、それぞれが自分のやり方で発言します。

弟子を持つことはほとんどなく、直接的な伝承はほとんどなかったようで、秘密結社などの存在もあまり知られていません。

それぞれが研究室で自分のために働き、孤独に苦しんでいた。

一方で、喧嘩はほとんどなかった。彼らの文章には比較的論争がなく、引用の仕方を見ても、何について合意しているのかはわからないが、第一原理については驚くほど一致している。

神学や哲学にありがちな論争や毛嫌いはほとんどありません。その理由は、"真の "錬金術が決してビジネスやキャリアではなく、静かで自己犠牲的な作業によって達成される真のオプスであったという事実にあるのでしょう。

各人が自分の経験を表現しようとし、マスターの言葉を引用したのは、それが類似していると思われる場合だけだったという印象があります。

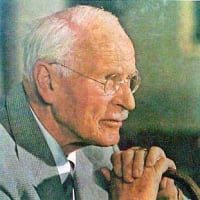

- カール・グスタフ・ユング『心理学と錬金術』P.312-314

アートワーク|サミュエル・ノートン《Mercurius redivivus》(1630年)-ヘルメス的変容の象徴:ホモ・フィロスポヒクス。

“For the alchemist the one primarily in need of redemption is not man, but the deity who is lost and sleeping in matter.”

“By pronouncing the consecrating words that bring about the transformation, the priest redeems the bread and the wine from their elemental imperfection as created things. This idea is quite unchristian—it is alchemical. Whereas Catholicism emphasises the effectual presence of Christ, alchemy is interested in the fate and manifest redemption of the substances, for in them the divine soul lies captive and awaits the redemption that is granted to it at the moment of release. The captive so then appears in the form of the “Son of God”.

For the alchemist the one primarily in need of redemption is not man, but the deity who is lost and sleeping in matter.

Only as a secondary consideration does he hope that some benefit may accrue to himself from the transformed substance as the panacea, the medicina catholica, just as it may to the imperfect bodies, the base or “sick” metals, etc.

His attention is not directed to his own salvation through God’s grace, but to the liberation of God from the darkness of matter.

By applying himself to this miraculous work he benefits from its salutary effect, but only incidentally. He may approach the work as one in need of salvation, but he knows that his salvation depends on the success of the work, on whether he can free the divine soul.

To this end he needs meditation, fasting, and prayer; more, he needs the help of the Holy Ghost as his (paredroz) ministering spirit.

Since it is not man but matter that must be redeemed, the spirit that manifests itself in the transformation is not the “Son of Man” but as Khunrath very properly puts it, the filius macrocosmi.

Therefore, what comes out of the transformation is not Christ but an ineffable material being named the “stone,” which displays the most paradoxical qualities apart from possessing corpus, anima, spiritus, and supernatural powers.

One might be tempted to explain the symbolism of alchemical transformation as a parody of the Mass were it not pagan in origin and much older than the latter.

The substance that harbors the divine secret is everywhere, including the human body. It can be had for the asking and can be found anywhere, even in the most loathsome filth.

In these circumstances the office is no longer a ritualistic officium, but the same work of redemption which God himself accomplished upon mankind through the example of Christ, and which is now recognised by the philosopher who has received the donum spiritus sancti(聖霊の賜物), the divine art, as his own individual opus.

The alchemists emphasise this point: “He who works through the spirit of another and by a hired hand will behold results that are far from the truth; and conversely he who gives his services to another as assistant in the laboratory will never be admitted to the Queen’s mysteries.”

One might quote the words of Kabasilas: “As kings, when they bring a gift to God, bear it themselves and do not permit to be borne by others.”

Alchemists are, in fact, decided solitaries; each has his say in his own way.

They rarely have pupils, and of direct tradition there seems to have been very little, nor is there much evidence of any secret societies or the like.

Each worked in the laboratory for himself and suffered from loneliness.

On the other hand, quarrels were rare. Their writings are relatively free of polemic, and the way they quote each other shows a remarkable agreement on first principles even if one cannot understand what they are really agreeing about.

There is little of that disputatiousness and splitting of hairs that so often mar theology and philosophy. The reason for this is probably the fact that “true” alchemy was never a business or a career, but a genuine opus to be achieved by quiet, self-sacrificing work.

One has the impression that each individual tried to express his own particular experiences, quoting the dicta of the Masters only when they seem to offer analogies.”

— Carl Gustav Jung, Psychology and Alchemy, P. 312-314

Artwork | Samuel Norton, Mercurius redivivus (1630) - Symbol of Hermetic transformation: the homo philospohicus.