パラクリート の到来は、元型的な転移の解決のイメージとして臨床的に理解できます。 したがって、分析の終わりに、転移の解決の問題が最重要であるとき、分析者はまったく同じメッセージを伝えなければなりません。 自己との関係は現れることはありません。」 そして、自己との内なる直接的な関係を促進するために、私たちは能動的な想像力を奨励しなければなりません。 分析の後半段階では、能動的な想像力が転移を解決するための主要な役割を果たします。 能動的な想像力はパラクリートを呼び起こします。

第 4 項、段落 657 および 658 は、継続的な受肉という非常に重要なテーマに関するものです。 この考えはユングの神話の核心です。

キリストにおける神の受肉には、継続と完了が必要です。なぜなら、キリストは、処女誕生と無罪のゆえに、まったく経験的な人間ではなかったからです。 聖ヨハネの第一章で述べられているように、彼は暗闇の中で輝いていても、暗闇には理解されなかった光を表していました。 彼は人類の外に留まり、人類の上に留まりました。 一方、ヨブは普通の人間であったため、ヨブに対して、またヨブを通して人類に対して行われた悪行は、神の正義によれば、経験的な人間における神の受肉によってのみ修復され得る。 この償いの行為はパラクリートによって行われます。 なぜなら、人間が神に対して苦しまなければならないのと同じように、神も人間に対して苦しまなければならないからである。 そうでなければ両者の間に和解はあり得ません。

神の子として召された人々に対する聖霊の継続的で直接的な働きは、実際、受肉の過程が拡大することを意味します。 神によって生まれた御子であるキリストは長子であり、その後はますます多くの弟や妹が後を継いでいきます。

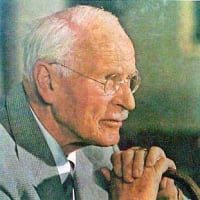

これが継続転生の考え方です。 これも個性化の過程を表現したものですが、そうでなければかなり抽象的な性質を持つ個性化の過程を、より鮮やかで刺激的な象徴としています。 ユングはこのテーマについては『ヨブへの答え』の後半でさらに詳しく述べていますが、最初にユングがエリン・コチュニッヒに宛てた手紙の一部を読んでみたいと思います。 英語で書かれたこの手紙は、新しいユング神話の主要なテキストであることを思い出していただきたいと思います。

人間の重要性は受肉によって強化されます。 私たちは神聖な生活の参加者となり、新たな責任を負わなければなりません。 それは私たちの個性化という課題の中で表現される神聖な自己実現の継続です。 個性化とは、人間が動物とは異なる真の人間になることを意味するだけでなく、部分的に神になることも意味します。 これは実質的に、人間が神に依存しているだけでなく、神も人間に依存していることを知り、自分の存在に責任を持って大人になることを意味します。 人間と神との関係は、おそらくある重要な変化を経る必要があるだろう。予測不可能な王に対する慰めの賛美や、愛情深い父親に対する子供の祈りの代わりに、私たちの内にある神の意志を責任を持って生き、実現することが、私たちの崇拝の形式となるだろう。 神との交易。 彼の善良さは恵みと光を意味し、彼の暗い側面は権力の恐ろしい誘惑を意味します。 [手紙、vol. 2、p. 316]

~エドワード・エディンガー、神の像の変容、75-78ページ

D

これらのコメントを読んでいると、では、他の信仰を持つ人々はどうなるのでしょうか?という疑問が私の心に生じます。 神の輝きはクリスチャンの心の中にだけ存在すると信じるほど愚かな人がいるでしょうか? 私はカトリック教徒として育てられましたが、十代の頃にカトリックから離れましたが、それには十分な理由がありました。 しかし今日に至るまで、クリスチャンの大多数は高級カントリークラブの会員であるかのような考え方を持っていることが分かりました。 私が信じているようにあなたが信じないなら、あなたは間違っており、あなたは地獄に落ちるでしょう。 それらすべてではありませんが、コメントに値する十分な割合があります。 個人的には、それは少し二段落だと思います。 キリストは、これまでに存在した唯一の精神的な哲学者や人物ではありません。 神は望み通りのどんな形でも姿を現すことができます。 この力がキリスト教において父親として描かれているという事実は、それが唯一可能な形式と表現であることを決して示しているわけではありません。

A

D

あなたが見逃しているように見える重要な要素は、ユングが正統キリスト教を含むいかなる宗教も役に立たなかったということです。なぜなら、それらはすべて信念に基づいており、聖書などのたとえ話を文字通りに受け取ることに迷っているからです。

これが個性化の本質です。群れで物語る社会集団や信念体系をすべて離れて個人になり、そうすれば人は無数に近づくことができるのです。

D

A

正確に。 この投稿に対して、キリスト教について掘り下げた返信がどれだけ多かったかに、私は驚いただけだと思います。 私はギリシャのストア派哲学者と同様に、仏教にも偉大な知恵を見出しています。 しかし最終的には超越が私たちの目標です

The coming of the Paraclete we can understand clinically as an image of the resolution of the archetypal transference. Thus, at the conclusion of an analysis, when the issue of the resolution of the transference is uppermost, the analyst must convey precisely the same message: "I must go and it is to your advantage that I go and unless I go your direct inner relation to the Self cannot appear." And in order to promote that inner direct relation to the Self we have to encourage active imagination. In the later phases of analysis active imagination is the primary agency for the resolution of the transference. Active imagination is the evocation of the Paraclete.

Item 4, paragraphs 657 and 658, concerns a really crucial theme, the continuing incarnation. This idea is the core of the Jungian myth:

God's Incarnation in Christ requires continuation and completion because Christ, owing to his virgin birth and his sinlessness, was not an empirical human being at all. As stated in the first chapter of St. John, he represented a light which, though it shone in the darkness, was not comprehended by the darkness. He remained outside and above mankind. Job, on the other hand, was an ordinary human being, and therefore the wrong done to him, and through him to mankind, can, according to divine justice, only be repaired by an incarnation of God in an empirical human being. This act of expiation is performed by the Paraclete; for, just as man must suffer from God, so God must suffer from man. Otherwise there can be no reconciliation between the two.

The continuing, direct operation of the Holy Ghost on those who are called to be God's children implies, in fact, a broadening process of incarnation. Christ, the son begotten by God, is the first-born who is succeeded by an ever-increasing number of younger brothers and sisters.

This is the idea of the continuing incarnation. It's another expression of the process of individuation but it's a more vivid, more evocative symbol for the process of individuation which otherwise has a rather abstract quality about it. Jung says more about this theme later on in Answer to Job, but I first want to read you part of a letter he wrote to Elined Kotschnig. I would like to remind you that this letter, written in English, is a major text of the new Jungian myth.

The significance of man is enhanced by the incarnation. We have become participants of the divine life and we have to assume a new responsibility, viz. the continuation of the divine self-realization, which expresses itself in the task of our individuation. Individuation does not only mean that man has become truly human as distinct from animal, but that he is to become partially divine as well. This means practically that he becomes adult, responsible for his existence, knowing that he does not only depend on God but that God also depends on man. Man's relation to God probably has to undergo a certain important change: Instead of the propitiating praise for an unpredictable king or the child's prayer to a loving father, the responsible living and fulfilling of the divine will in us will be our form of worship of and commerce with God. His goodness means grace and light and His dark side the terrible temptation of power. [Letters, vol. 2, p. 316]

~Edward Edinger, Transformation of the God-Image, Pages 75-78

D

From reading these comments, the question arises in my mind, what then of people of other faiths? Are some foolish enough to believe that the spark of God exists only in the hearts of christians? I was raised catholic, but walked away from it as a teenager, for very good reasons. But to this day, I find the vast majority of Christians have the mentality of being a member of an exclusive country club. If you don't believe as I believe, you're wrong and you're going to hell. Not all of them, but a significant enough percentage to merit comment. Personally, I think that's a little bunk. Christ is not the only spiritual philosopher or figure to ever have existed. God can manifest itself in any form it wishes. The fact that this force is portrayed as the father in christianity, is in no way an indication that that is it's only possible form and expression

A

D

An important factor that you seem to be missing is how Jung had no use for any religions including orthodox Christianity because they are all Belief-based and are lost in taking the bible, etc., parables literally.

This is what Individuation is much about – leaving all herd-narrative social groups and belief systems in order to become an Individual and then one can approach the numinous.

D

A

precisely. I suppose I was just taken by surprise, how many of the replies delved into christianity in response to this post. I do find great wisdom in buddhism, as well as the Greek stoic philosophers. But ultimately, Transcendence is our goal

第 4 項、段落 657 および 658 は、継続的な受肉という非常に重要なテーマに関するものです。 この考えはユングの神話の核心です。

キリストにおける神の受肉には、継続と完了が必要です。なぜなら、キリストは、処女誕生と無罪のゆえに、まったく経験的な人間ではなかったからです。 聖ヨハネの第一章で述べられているように、彼は暗闇の中で輝いていても、暗闇には理解されなかった光を表していました。 彼は人類の外に留まり、人類の上に留まりました。 一方、ヨブは普通の人間であったため、ヨブに対して、またヨブを通して人類に対して行われた悪行は、神の正義によれば、経験的な人間における神の受肉によってのみ修復され得る。 この償いの行為はパラクリートによって行われます。 なぜなら、人間が神に対して苦しまなければならないのと同じように、神も人間に対して苦しまなければならないからである。 そうでなければ両者の間に和解はあり得ません。

神の子として召された人々に対する聖霊の継続的で直接的な働きは、実際、受肉の過程が拡大することを意味します。 神によって生まれた御子であるキリストは長子であり、その後はますます多くの弟や妹が後を継いでいきます。

これが継続転生の考え方です。 これも個性化の過程を表現したものですが、そうでなければかなり抽象的な性質を持つ個性化の過程を、より鮮やかで刺激的な象徴としています。 ユングはこのテーマについては『ヨブへの答え』の後半でさらに詳しく述べていますが、最初にユングがエリン・コチュニッヒに宛てた手紙の一部を読んでみたいと思います。 英語で書かれたこの手紙は、新しいユング神話の主要なテキストであることを思い出していただきたいと思います。

人間の重要性は受肉によって強化されます。 私たちは神聖な生活の参加者となり、新たな責任を負わなければなりません。 それは私たちの個性化という課題の中で表現される神聖な自己実現の継続です。 個性化とは、人間が動物とは異なる真の人間になることを意味するだけでなく、部分的に神になることも意味します。 これは実質的に、人間が神に依存しているだけでなく、神も人間に依存していることを知り、自分の存在に責任を持って大人になることを意味します。 人間と神との関係は、おそらくある重要な変化を経る必要があるだろう。予測不可能な王に対する慰めの賛美や、愛情深い父親に対する子供の祈りの代わりに、私たちの内にある神の意志を責任を持って生き、実現することが、私たちの崇拝の形式となるだろう。 神との交易。 彼の善良さは恵みと光を意味し、彼の暗い側面は権力の恐ろしい誘惑を意味します。 [手紙、vol. 2、p. 316]

~エドワード・エディンガー、神の像の変容、75-78ページ

D

これらのコメントを読んでいると、では、他の信仰を持つ人々はどうなるのでしょうか?という疑問が私の心に生じます。 神の輝きはクリスチャンの心の中にだけ存在すると信じるほど愚かな人がいるでしょうか? 私はカトリック教徒として育てられましたが、十代の頃にカトリックから離れましたが、それには十分な理由がありました。 しかし今日に至るまで、クリスチャンの大多数は高級カントリークラブの会員であるかのような考え方を持っていることが分かりました。 私が信じているようにあなたが信じないなら、あなたは間違っており、あなたは地獄に落ちるでしょう。 それらすべてではありませんが、コメントに値する十分な割合があります。 個人的には、それは少し二段落だと思います。 キリストは、これまでに存在した唯一の精神的な哲学者や人物ではありません。 神は望み通りのどんな形でも姿を現すことができます。 この力がキリスト教において父親として描かれているという事実は、それが唯一可能な形式と表現であることを決して示しているわけではありません。

A

D

あなたが見逃しているように見える重要な要素は、ユングが正統キリスト教を含むいかなる宗教も役に立たなかったということです。なぜなら、それらはすべて信念に基づいており、聖書などのたとえ話を文字通りに受け取ることに迷っているからです。

これが個性化の本質です。群れで物語る社会集団や信念体系をすべて離れて個人になり、そうすれば人は無数に近づくことができるのです。

D

A

正確に。 この投稿に対して、キリスト教について掘り下げた返信がどれだけ多かったかに、私は驚いただけだと思います。 私はギリシャのストア派哲学者と同様に、仏教にも偉大な知恵を見出しています。 しかし最終的には超越が私たちの目標です

The coming of the Paraclete we can understand clinically as an image of the resolution of the archetypal transference. Thus, at the conclusion of an analysis, when the issue of the resolution of the transference is uppermost, the analyst must convey precisely the same message: "I must go and it is to your advantage that I go and unless I go your direct inner relation to the Self cannot appear." And in order to promote that inner direct relation to the Self we have to encourage active imagination. In the later phases of analysis active imagination is the primary agency for the resolution of the transference. Active imagination is the evocation of the Paraclete.

Item 4, paragraphs 657 and 658, concerns a really crucial theme, the continuing incarnation. This idea is the core of the Jungian myth:

God's Incarnation in Christ requires continuation and completion because Christ, owing to his virgin birth and his sinlessness, was not an empirical human being at all. As stated in the first chapter of St. John, he represented a light which, though it shone in the darkness, was not comprehended by the darkness. He remained outside and above mankind. Job, on the other hand, was an ordinary human being, and therefore the wrong done to him, and through him to mankind, can, according to divine justice, only be repaired by an incarnation of God in an empirical human being. This act of expiation is performed by the Paraclete; for, just as man must suffer from God, so God must suffer from man. Otherwise there can be no reconciliation between the two.

The continuing, direct operation of the Holy Ghost on those who are called to be God's children implies, in fact, a broadening process of incarnation. Christ, the son begotten by God, is the first-born who is succeeded by an ever-increasing number of younger brothers and sisters.

This is the idea of the continuing incarnation. It's another expression of the process of individuation but it's a more vivid, more evocative symbol for the process of individuation which otherwise has a rather abstract quality about it. Jung says more about this theme later on in Answer to Job, but I first want to read you part of a letter he wrote to Elined Kotschnig. I would like to remind you that this letter, written in English, is a major text of the new Jungian myth.

The significance of man is enhanced by the incarnation. We have become participants of the divine life and we have to assume a new responsibility, viz. the continuation of the divine self-realization, which expresses itself in the task of our individuation. Individuation does not only mean that man has become truly human as distinct from animal, but that he is to become partially divine as well. This means practically that he becomes adult, responsible for his existence, knowing that he does not only depend on God but that God also depends on man. Man's relation to God probably has to undergo a certain important change: Instead of the propitiating praise for an unpredictable king or the child's prayer to a loving father, the responsible living and fulfilling of the divine will in us will be our form of worship of and commerce with God. His goodness means grace and light and His dark side the terrible temptation of power. [Letters, vol. 2, p. 316]

~Edward Edinger, Transformation of the God-Image, Pages 75-78

D

From reading these comments, the question arises in my mind, what then of people of other faiths? Are some foolish enough to believe that the spark of God exists only in the hearts of christians? I was raised catholic, but walked away from it as a teenager, for very good reasons. But to this day, I find the vast majority of Christians have the mentality of being a member of an exclusive country club. If you don't believe as I believe, you're wrong and you're going to hell. Not all of them, but a significant enough percentage to merit comment. Personally, I think that's a little bunk. Christ is not the only spiritual philosopher or figure to ever have existed. God can manifest itself in any form it wishes. The fact that this force is portrayed as the father in christianity, is in no way an indication that that is it's only possible form and expression

A

D

An important factor that you seem to be missing is how Jung had no use for any religions including orthodox Christianity because they are all Belief-based and are lost in taking the bible, etc., parables literally.

This is what Individuation is much about – leaving all herd-narrative social groups and belief systems in order to become an Individual and then one can approach the numinous.

D

A

precisely. I suppose I was just taken by surprise, how many of the replies delved into christianity in response to this post. I do find great wisdom in buddhism, as well as the Greek stoic philosophers. But ultimately, Transcendence is our goal

A

Ⅲ.聖霊 (ユングCW 11)

[234] 人間と三位一体の生活過程との心理的関係は、第一にキリストの人間性によって示され、第二にキリスト教のメッセージによって予言され約束された聖霊の降臨と聖霊の人間の内住によって示される。 キリストの生涯は、一方ではメッセージを宣言するための短い歴史的な幕間にすぎませんが、他方では、それは神のご自身の現れ(または自己の実現)に関連した精神的経験の模範的な実証でもあります。 人間にとって重要なことは、そのこと(「示された」ことや「行われた」こと)ではなく、その後に何が起こるか、つまり聖霊によって個人が捕らえられることです。

[235] しかし、ここで私たちは大きな困難に遭遇します。 なぜなら、私たちが聖霊の理論を追跡し、それをさらに一歩進めれば(明白な理由で教会はそれをしませんでしたが)、必然的に、父が息子の中に現れ、息子と一緒に呼吸するならば、という結論に達するからです。 そして、御子が人間のために聖霊を置き去りにし、そのとき聖霊が人間の中に息を吹き込み、それが人間、御子、御父に共通の息となるのです。 したがって、人間は神の子に含まれており、「あなたがたは神である」(ヨハネ 10:34)というキリストの言葉が重要な意味を持って現れます。 パラクリーテが人類のために明示的に残されたという学説は、大きな問題を引き起こします。 論理の問題では、プラトンの三項公式が確かに最後の言葉になるでしょうが、心理学的にはまったくそうではありません。心理的要因が最も不安な方法で侵入し続けるためです。 素晴らしいことなのに、どうして「父、母、そして息子」ではなかったのでしょう? それは、「父と子と聖霊」よりもはるかに「合理的」で「自然」でしょう。 これに対して私たちは答えなければなりません。それは単に自然な状況の問題ではなく、人間の反省の産物であり、父と息子の自然な順序に加えられたものなのです。 反省を通じて、「生命」とその「魂」は自然から抽象化され、独立した存在を与えられます。 父と子は同じ魂で結ばれており、古代エジプトの見解によれば、同じ生殖力、カ・ムテフで結ばれています。 カ・ムテフは、神格の息吹や「霊感」とまったく同じ属性の仮説化です。 10

[236] この心理的事実は、三項式の抽象的な完全性を台無しにし、それを論理的に理解できない構造にしてしまう。なぜなら、何らかの神秘的かつ予期せぬ方法で、人間に特有の重要な精神過程がそこに持ち込まれているからである。 聖霊が同時に生命の息吹であり、愛に満ちた霊であり、三位一体の過程全体が頂点に達する第三者であるならば、聖霊は本質的に反省の産物であり、父と息子という自然な家族像に付け加えられた偽りの観念論である。 初期のキリスト教グノーシス主義が聖霊を母として解釈することでこの困難を回避しようとしたことは重要です。 [11] しかし、それは単に彼を古風な家族像、家父長制世界の三神教と多神教の中に閉じ込めただけだろう。 結局のところ、父親が家族を持ち、息子が父親を体現するのは完全に自然なことです。 この思考の流れは父親の世界と非常に一致しています。 一方、母親の解釈は、聖霊の具体的な意味を原始的なイメージに還元し、聖霊に帰せられる特質の最も本質的なものを破壊することになるでしょう。聖霊は父と子に共通の命であるだけでなく、聖霊は聖霊を司るパラクレートでもあります。 御子は人間の中で子孫を残し、神の親子関係の業を生み出すために、彼の後に残されました。 聖霊の概念が自然なイメージではなく、父と子の生きた性質の認識であり、一方と他方の間の「第三の」用語として抽象的に考えられていることが最も重要です。 二元性の緊張から、人生は常に、どういうわけか比較不可能または逆説的に見える「第三の」を生み出します。 したがって、聖霊は「第三」として、計り知れない、そして逆説的であるはずです。 父と子とは異なり、彼には名前も性格もありません。 彼は機能ですが、その機能は神の三人称です。

A

III. THE HOLY GHOST (Jung CW 11)

[234] The psychological relationship between man and the trinitarian life process is illustrated first by the human nature of Christ, and second by the descent of the Holy Ghost and his indwelling in man, as predicted and promised by the Christian message. The life of Christ is on the one hand only a short, historical interlude for proclaiming the message, but on the other hand it is an exemplary demonstration of the psychic experiences connected with God’s manifestation of himself (or the realization of the self). The important thing for man is not the and the (what is “shown” and “done”), but what happens afterwards: the seizure of the individual by the Holy Ghost.

[235] Here, however, we run into a great difficulty. For if we follow up the theory of the Holy Ghost and carry it a step further (which the Church has not done, for obvious reasons), we come inevitably to the conclusion that if the Father appears in the Son and breathes together with the Son, and the Son leaves the Holy Ghost behind for man, then the Holy Ghost breathes in man, too, and thus is the breath common to man, the Son, and the Father. Man is therefore included in God’s sonship, and the words of Christ—“Ye are gods” (John 10:34)—appear in a significant light. The doctrine that the Paraclete was expressly left behind for man raises an enormous problem. The triadic formula of Plato would surely be the last word in the matter of logic, but psychologically it is not so at all, because the psychological factor keeps on intruding in the most disturbing way. Why, in the name of all that’s wonderful, wasn’t it “Father, Mother, and Son?” That would be much more “reasonable” and “natural” than “Father, Son, and Holy Ghost.” To this we must answer: it is not just a question of a natural situation, but of a product of human reflection 9 added on to the natural sequence of father and son. Through reflection, “life” and its “soul” are abstracted from Nature and endowed with a separate existence. Father and son are united in the same soul, or, according to the ancient Egyptian view, in the same procreative force, Ka-mutef. Ka-mutef is exactly the same hypostatization of an attribute as the breath or “spiration” of the Godhead. 10

[236] This psychological fact spoils the abstract perfection of the triadic formula and makes it a logically incomprehensible construction, since, in some mysterious and unexpected way, an important mental process peculiar to man has been imported into it. If the Holy Ghost is, at one and the same time, the breath of life and a loving spirit and the Third Person in whom the whole trinitarian process culminates, then he is essentially a product of reflection, an hypostatized noumenon tacked on to the natural family-picture of father and son. It is significant that early Christian Gnosticism tried to get round this difficulty by interpreting the Holy Ghost as the Mother. 11 But that would merely have kept him within the archaic family-picture, within the tritheism and polytheism of the patriarchal world. It is, after all, perfectly natural that the father should have a family and that the son should embody the father. This train of thought is quite consistent with the father-world. On the other hand, the motherinterpretation would reduce the specific meaning of the Holy Ghost to a primitive image and destroy the most essential of the qualities attributed to him: not only is he the life common to Father and Son, he is also the Paraclete whom the Son left behind him, to procreate in man and bring forth works of divine parentage. It is of paramount importance that the idea of the Holy Ghost is not a natural image, but a recognition of the living quality of Father and Son, abstractly conceived as the “third” term between the One and the Other. Out of the tension of duality life always produces a “third” that seems somehow incommensurable or paradoxical. Hence, as the “third,” the Holy Ghost is bound to be incommensurable and paradoxical too. Unlike Father and Son, he has no name and no character. He is a function, but that function is the Third Person of the Godhead.

Ⅲ.聖霊 (ユングCW 11)

[234] 人間と三位一体の生活過程との心理的関係は、第一にキリストの人間性によって示され、第二にキリスト教のメッセージによって予言され約束された聖霊の降臨と聖霊の人間の内住によって示される。 キリストの生涯は、一方ではメッセージを宣言するための短い歴史的な幕間にすぎませんが、他方では、それは神のご自身の現れ(または自己の実現)に関連した精神的経験の模範的な実証でもあります。 人間にとって重要なことは、そのこと(「示された」ことや「行われた」こと)ではなく、その後に何が起こるか、つまり聖霊によって個人が捕らえられることです。

[235] しかし、ここで私たちは大きな困難に遭遇します。 なぜなら、私たちが聖霊の理論を追跡し、それをさらに一歩進めれば(明白な理由で教会はそれをしませんでしたが)、必然的に、父が息子の中に現れ、息子と一緒に呼吸するならば、という結論に達するからです。 そして、御子が人間のために聖霊を置き去りにし、そのとき聖霊が人間の中に息を吹き込み、それが人間、御子、御父に共通の息となるのです。 したがって、人間は神の子に含まれており、「あなたがたは神である」(ヨハネ 10:34)というキリストの言葉が重要な意味を持って現れます。 パラクリーテが人類のために明示的に残されたという学説は、大きな問題を引き起こします。 論理の問題では、プラトンの三項公式が確かに最後の言葉になるでしょうが、心理学的にはまったくそうではありません。心理的要因が最も不安な方法で侵入し続けるためです。 素晴らしいことなのに、どうして「父、母、そして息子」ではなかったのでしょう? それは、「父と子と聖霊」よりもはるかに「合理的」で「自然」でしょう。 これに対して私たちは答えなければなりません。それは単に自然な状況の問題ではなく、人間の反省の産物であり、父と息子の自然な順序に加えられたものなのです。 反省を通じて、「生命」とその「魂」は自然から抽象化され、独立した存在を与えられます。 父と子は同じ魂で結ばれており、古代エジプトの見解によれば、同じ生殖力、カ・ムテフで結ばれています。 カ・ムテフは、神格の息吹や「霊感」とまったく同じ属性の仮説化です。 10

[236] この心理的事実は、三項式の抽象的な完全性を台無しにし、それを論理的に理解できない構造にしてしまう。なぜなら、何らかの神秘的かつ予期せぬ方法で、人間に特有の重要な精神過程がそこに持ち込まれているからである。 聖霊が同時に生命の息吹であり、愛に満ちた霊であり、三位一体の過程全体が頂点に達する第三者であるならば、聖霊は本質的に反省の産物であり、父と息子という自然な家族像に付け加えられた偽りの観念論である。 初期のキリスト教グノーシス主義が聖霊を母として解釈することでこの困難を回避しようとしたことは重要です。 [11] しかし、それは単に彼を古風な家族像、家父長制世界の三神教と多神教の中に閉じ込めただけだろう。 結局のところ、父親が家族を持ち、息子が父親を体現するのは完全に自然なことです。 この思考の流れは父親の世界と非常に一致しています。 一方、母親の解釈は、聖霊の具体的な意味を原始的なイメージに還元し、聖霊に帰せられる特質の最も本質的なものを破壊することになるでしょう。聖霊は父と子に共通の命であるだけでなく、聖霊は聖霊を司るパラクレートでもあります。 御子は人間の中で子孫を残し、神の親子関係の業を生み出すために、彼の後に残されました。 聖霊の概念が自然なイメージではなく、父と子の生きた性質の認識であり、一方と他方の間の「第三の」用語として抽象的に考えられていることが最も重要です。 二元性の緊張から、人生は常に、どういうわけか比較不可能または逆説的に見える「第三の」を生み出します。 したがって、聖霊は「第三」として、計り知れない、そして逆説的であるはずです。 父と子とは異なり、彼には名前も性格もありません。 彼は機能ですが、その機能は神の三人称です。

A

III. THE HOLY GHOST (Jung CW 11)

[234] The psychological relationship between man and the trinitarian life process is illustrated first by the human nature of Christ, and second by the descent of the Holy Ghost and his indwelling in man, as predicted and promised by the Christian message. The life of Christ is on the one hand only a short, historical interlude for proclaiming the message, but on the other hand it is an exemplary demonstration of the psychic experiences connected with God’s manifestation of himself (or the realization of the self). The important thing for man is not the and the (what is “shown” and “done”), but what happens afterwards: the seizure of the individual by the Holy Ghost.

[235] Here, however, we run into a great difficulty. For if we follow up the theory of the Holy Ghost and carry it a step further (which the Church has not done, for obvious reasons), we come inevitably to the conclusion that if the Father appears in the Son and breathes together with the Son, and the Son leaves the Holy Ghost behind for man, then the Holy Ghost breathes in man, too, and thus is the breath common to man, the Son, and the Father. Man is therefore included in God’s sonship, and the words of Christ—“Ye are gods” (John 10:34)—appear in a significant light. The doctrine that the Paraclete was expressly left behind for man raises an enormous problem. The triadic formula of Plato would surely be the last word in the matter of logic, but psychologically it is not so at all, because the psychological factor keeps on intruding in the most disturbing way. Why, in the name of all that’s wonderful, wasn’t it “Father, Mother, and Son?” That would be much more “reasonable” and “natural” than “Father, Son, and Holy Ghost.” To this we must answer: it is not just a question of a natural situation, but of a product of human reflection 9 added on to the natural sequence of father and son. Through reflection, “life” and its “soul” are abstracted from Nature and endowed with a separate existence. Father and son are united in the same soul, or, according to the ancient Egyptian view, in the same procreative force, Ka-mutef. Ka-mutef is exactly the same hypostatization of an attribute as the breath or “spiration” of the Godhead. 10

[236] This psychological fact spoils the abstract perfection of the triadic formula and makes it a logically incomprehensible construction, since, in some mysterious and unexpected way, an important mental process peculiar to man has been imported into it. If the Holy Ghost is, at one and the same time, the breath of life and a loving spirit and the Third Person in whom the whole trinitarian process culminates, then he is essentially a product of reflection, an hypostatized noumenon tacked on to the natural family-picture of father and son. It is significant that early Christian Gnosticism tried to get round this difficulty by interpreting the Holy Ghost as the Mother. 11 But that would merely have kept him within the archaic family-picture, within the tritheism and polytheism of the patriarchal world. It is, after all, perfectly natural that the father should have a family and that the son should embody the father. This train of thought is quite consistent with the father-world. On the other hand, the motherinterpretation would reduce the specific meaning of the Holy Ghost to a primitive image and destroy the most essential of the qualities attributed to him: not only is he the life common to Father and Son, he is also the Paraclete whom the Son left behind him, to procreate in man and bring forth works of divine parentage. It is of paramount importance that the idea of the Holy Ghost is not a natural image, but a recognition of the living quality of Father and Son, abstractly conceived as the “third” term between the One and the Other. Out of the tension of duality life always produces a “third” that seems somehow incommensurable or paradoxical. Hence, as the “third,” the Holy Ghost is bound to be incommensurable and paradoxical too. Unlike Father and Son, he has no name and no character. He is a function, but that function is the Third Person of the Godhead.

[237] 彼は、父と息子の関係から論理的に導き出すことができず、人間の熟考のプロセスによって導入されたアイデアとしてのみ理解できるという点で、心理的に異質です。 聖霊は極めて「抽象的な」概念です。なぜなら、別個で相互に交換不可能であると特徴づけられる二人の人物が共有する「息」など、まったく考えられないからです。 したがって、エジプトのカ・ムテフの概念が示すように、それはどういうわけか三位一体のまさに本質に属しているように見えますが、人はそれが心の人工的な構築物であると感じます。 このような概念の設定には人間の反省の産物と見ざるを得ないという事実にもかかわらず、この反省は必ずしも意識的な行為である必要はありません。 それは同様に、その存在が「啓示」、つまり無意識の反映によるものである可能性があり、したがって無意識、あるいはむしろ自己の自律的な機能によるものである可能性があり、すでに述べたように、そのシンボルは神の像と区別することができません。 したがって、宗教的解釈は、この仮説は神の啓示であると主張するでしょう。 このような概念に異議を唱えることはできませんが、心理学はヒポスタシスの概念的な性質をしっかりと保持しなければなりません。なぜなら、最終的には三位一体も擬人化された構成であり、精力的な精神的および精神的な努力を通じて徐々に形をとっていくからです。 時代を超越した元型によってすでに形成されています。

[238] この性質の分離、認識、割り当ては精神的な活動であり、最初は無意識ですが、作業が進むにつれて徐々に意識へと浸透していきます。 最初は単に意識に起こったことが、後にそれ自体の活動として意識に統合されます。 精神的プロセス、あるいは実際にあらゆる精神的プロセスが無意識である限り、それは自己の周りに組織され配置された元型的な性質を支配する法則の影響を受けます。 そして、自己は元型的な神の像と区別できないので、そのような取り決めについて、それが自然法に従っており、神の意志の行為であると言うのも同様に真実でしょう。 (あらゆる形而上学的な言明は、当然のことながら証明不可能である)。 したがって、認識と判断の行為は意識の本質的な特質であるため、無意識を徹底的に分析すればわかるように、この種の無意識的行為の蓄積は意識を強化し、拡大する効果を持つことになります。 その結果、人間の意識の達成は、予兆的な元型的なプロセスの結果として、あるいは形而上学的に言えば、神の生命プロセスの一部として現れる。 言い換えれば、神は人間の反省の行為の中に現れるのです。

[...]

[237] He is psychologically heterogeneous in that he cannot be logically derived from the father-son relationship and can only be understood as an idea introduced by a process of human reflection. The Holy Ghost is an exceedingly “abstract” conception, since a “breath” shared by two figures characterized as distinct and not mutually interchangeable can hardly be conceived at all. Hence one feels it to be an artificial construction of the mind, even though, as the Egyptian Ka-mutef concept shows, it seems somehow to belong to the very essence of the Trinity. Despite the fact that we cannot help seeing in the positing of such a concept a product of human reflection, this reflection need not necessarily have been a conscious act. It could equally well owe its existence to a “revelation,” i.e., to an unconscious reflection, 12 and hence to an autonomous functioning of the unconscious, or rather of the self, whose symbols, as we have already said, cannot be distinguished from God-images. A religious interpretation will therefore insist that this hypostasis was a divine revelation. While it cannot raise any objections to such a notion, psychology must hold fast to the conceptual nature of the hypostasis, for in the last analysis the Trinity, too, is an anthropomorphic configuration, gradually taking shape through strenuous mental and spiritual effort, even though already preformed by the timeless archetype.

[238] This separating, recognizing, and assigning of qualities is a mental activity which, although unconscious at first, gradually filters through to consciousness as the work proceeds. What started off by merely happening to consciousness later becomes integrated in it as its own activity. So long as a mental or indeed any psychic process at all is unconscious, it is subject to the law governing archetypal dispositions, which are organized and arranged round the self. And since the self cannot be distinguished from an archetypal God-image, it would be equally true to say of any such arrangement that it conforms to natural law and that it is an act of God’s will. (Every metaphysical statement is, ipso facto, unprovable). Inasmuch, then, as acts of cognition and judgment are essential qualities of consciousness, any accumulation of unconscious acts of this sort 13 will have the effect of strengthening and widening consciousness, as one can see for oneself in any thorough analysis of the unconscious. Consequently, man’s achievement of consciousness appears as the result of prefigurative archetypal processes or—to put it metaphysically—as part of the divine life-process. In other words, God becomes manifest in the human act of reflection.

[...]

[238] この性質の分離、認識、割り当ては精神的な活動であり、最初は無意識ですが、作業が進むにつれて徐々に意識へと浸透していきます。 最初は単に意識に起こったことが、後にそれ自体の活動として意識に統合されます。 精神的プロセス、あるいは実際にあらゆる精神的プロセスが無意識である限り、それは自己の周りに組織され配置された元型的な性質を支配する法則の影響を受けます。 そして、自己は元型的な神の像と区別できないので、そのような取り決めについて、それが自然法に従っており、神の意志の行為であると言うのも同様に真実でしょう。 (あらゆる形而上学的な言明は、当然のことながら証明不可能である)。 したがって、認識と判断の行為は意識の本質的な特質であるため、無意識を徹底的に分析すればわかるように、この種の無意識的行為の蓄積は意識を強化し、拡大する効果を持つことになります。 その結果、人間の意識の達成は、予兆的な元型的なプロセスの結果として、あるいは形而上学的に言えば、神の生命プロセスの一部として現れる。 言い換えれば、神は人間の反省の行為の中に現れるのです。

[...]

[237] He is psychologically heterogeneous in that he cannot be logically derived from the father-son relationship and can only be understood as an idea introduced by a process of human reflection. The Holy Ghost is an exceedingly “abstract” conception, since a “breath” shared by two figures characterized as distinct and not mutually interchangeable can hardly be conceived at all. Hence one feels it to be an artificial construction of the mind, even though, as the Egyptian Ka-mutef concept shows, it seems somehow to belong to the very essence of the Trinity. Despite the fact that we cannot help seeing in the positing of such a concept a product of human reflection, this reflection need not necessarily have been a conscious act. It could equally well owe its existence to a “revelation,” i.e., to an unconscious reflection, 12 and hence to an autonomous functioning of the unconscious, or rather of the self, whose symbols, as we have already said, cannot be distinguished from God-images. A religious interpretation will therefore insist that this hypostasis was a divine revelation. While it cannot raise any objections to such a notion, psychology must hold fast to the conceptual nature of the hypostasis, for in the last analysis the Trinity, too, is an anthropomorphic configuration, gradually taking shape through strenuous mental and spiritual effort, even though already preformed by the timeless archetype.

[238] This separating, recognizing, and assigning of qualities is a mental activity which, although unconscious at first, gradually filters through to consciousness as the work proceeds. What started off by merely happening to consciousness later becomes integrated in it as its own activity. So long as a mental or indeed any psychic process at all is unconscious, it is subject to the law governing archetypal dispositions, which are organized and arranged round the self. And since the self cannot be distinguished from an archetypal God-image, it would be equally true to say of any such arrangement that it conforms to natural law and that it is an act of God’s will. (Every metaphysical statement is, ipso facto, unprovable). Inasmuch, then, as acts of cognition and judgment are essential qualities of consciousness, any accumulation of unconscious acts of this sort 13 will have the effect of strengthening and widening consciousness, as one can see for oneself in any thorough analysis of the unconscious. Consequently, man’s achievement of consciousness appears as the result of prefigurative archetypal processes or—to put it metaphysically—as part of the divine life-process. In other words, God becomes manifest in the human act of reflection.

[...]

A

[...]

[239] この概念の性質(つまり、性質の仮説化)は、個々の性質にそれ自体の具体的な存在を与えることによって、多かれ少なかれ抽象的なアイデアを形成するという原始的思考によって明らかにされた必要性を満たします。 聖霊が人間に残された遺産であるのと同じように、逆に、聖霊の概念は人間によって生み出されたものであり、人間の祖先の刻印が刻まれています。 そして、キリストが人間の肉体的な本性を帯びたのと同じように、聖霊を通して人間は霊的な力として密かに三位一体の神秘に組み込まれ、それによって三位一体の自然主義的なレベルをはるかに超え、したがってプラトンの三位一体を超えたものとなります。 したがって、三位一体は、神と人間の本質を理解する象徴としてそれ自体を明らかにします。 ケプゲン 14 章にあるように、それは「神の啓示であるだけでなく、同時に人間の啓示でもある」のです。

[240] 聖霊を母とするグノーシス派の解釈には、マリアが神の誕生の道具であり、したがって人間として三位一体のドラマに関与するようになったという真実の核心が含まれています。 したがって、神の母は、三位一体への人類の本質的な参加の象徴とみなすことができます。 この仮定の心理学的正当化は、もともと無意識の自己啓示にその源を持っていた思考が、意識の外部の力の現れであると感じられていたという事実にあります。 原始人は考えません。 という考えが彼に伝わってきます。 私たち自身も、特定の特に啓発的なアイデアを「影響力」や「インスピレーション」などとして今でも感じています。判断や洞察の閃きが無意識の活動によって伝達される場合、それらは多くの場合、元型的な女性像、アニマ、または最愛の母親に起因すると考えられます。 すると、あたかもそのインスピレーションが母親や愛する人、つまり「ファム・インスピラトリス」から来たかのように見えます。 このことを考慮すると、聖霊はご自身の中性的な呼称( )を女性的な呼称に交換する傾向があるでしょう。 (精神を意味するヘブライ語のルアハは主に女性名詞であることに注意してください。)聖霊とロゴスは、ソフィアのグノーシス主義の考えの中で融合し、また中世の自然哲学者のサピエンティアの中で融合します。ソフィアは彼女についてこう言いました。 「matris sedet sapientia patris」(父親の知恵は母親の膝の上にある)。 これらの心理的関係は、なぜ聖霊が母親として解釈されたのかを説明するものではありますが、聖霊そのものについての私たちの理解には何も加えません。母親の本来の立場が 2 番目であるときに、どうして母親が 3 番目になることができるのかを理解することは不可能だからです。 。

[241] 聖霊は反省の行為によって仮定された「生命」の仮説であるため、聖霊はその特異な性質により、別個の比較不能な「第三」として現れ、その特異性そのものが、聖霊が生命のどちらでもないことを証明している。 それは妥協ではなく、単なる三要素の付属物ではなく、むしろ父と子の間の緊張の論理的に予想外の解決です。 団結する「第三」を不合理に生み出すのはまさに人間の反省のプロセスであるという事実自体が、神が人間の領域に降臨し、人間が神の領域に登るという救済のドラマの性質と関係している。

A

[...]

[239] The nature of this conception (i.e., the hypostatizing of a quality) meets the need evinced by primitive thought to form a more or less abstract idea by endowing each individual quality with a concrete existence of its own. Just as the Holy Ghost is a legacy left to man, so, conversely, the concept of the Holy Ghost is something begotten by man and bears the stamp of its human progenitor. And just as Christ took on man’s bodily nature, so through the Holy Ghost man as a spiritual force is surreptitiously included in the mystery of the Trinity, thereby raising it far above the naturalistic level of the triad and thus beyond the Platonic triunity. The Trinity, therefore, discloses itself as a symbol that comprehends the essence of the divine and the human. It is, as Koepgen 14 says, “a revelation not only of God but at the same time of man.”

[240] The Gnostic interpretation of the Holy Ghost as the Mother contains a core of truth in that Mary was the instrument of God’s birth and so became involved in the trinitarian drama as a human being. The Mother of God can, therefore, be regarded as a symbol of mankind’s essential participation in the Trinity. The psychological justification for this assumption lies in the fact that thinking, which originally had its source in the self-revelations of the unconscious, was felt to be the manifestation of a power external to consciousness. The primitive does not think; the thoughts come to him. We ourselves still feel certain particularly enlightening ideas as “in-fluences,” “in-spirations,” etc. Where judgments and flashes of insight are transmitted by unconscious activity, they are often attributed to an archetypal feminine figure, the anima or motherbeloved. It then seems as if the inspiration came from the mother or from the beloved, the “femme inspiratrice.” In view of this, the Holy Ghost would have a tendency to exchange his neuter designation ( ) for a feminine one. (It may be noted that the Hebrew word for spirit—ruach— is predominantly feminine.) Holy Ghost and Logos merge in the Gnostic idea of Sophia, and again in the Sapientia of the medieval natural philosophers, who said of her: “In gremio matris sedet sapientia patris” (the wisdom of the father lies in the lap of the mother). These psychological relationships do something to explain why the Holy Ghost was interpreted as the mother, but they add nothing to our understanding of the Holy Ghost as such, because it is impossible to see how the mother could come third when her natural place would be second.

[241] Since the Holy Ghost is an hypostasis of “life,” posited by an act of reflection, he appears, on account of his peculiar nature, as a separate and incommensurable “third,” whose very peculiarities testify that it is neither a compromise nor a mere triadic appendage, but rather the logically unexpected resolution of tension between Father and Son. The fact that it is precisely a process of human reflection that irrationally creates the uniting “third” is itself connected with the nature of the drama of redemption, whereby God descends into the human realm and man mounts up to the realm of divinity.

[...]

[239] この概念の性質(つまり、性質の仮説化)は、個々の性質にそれ自体の具体的な存在を与えることによって、多かれ少なかれ抽象的なアイデアを形成するという原始的思考によって明らかにされた必要性を満たします。 聖霊が人間に残された遺産であるのと同じように、逆に、聖霊の概念は人間によって生み出されたものであり、人間の祖先の刻印が刻まれています。 そして、キリストが人間の肉体的な本性を帯びたのと同じように、聖霊を通して人間は霊的な力として密かに三位一体の神秘に組み込まれ、それによって三位一体の自然主義的なレベルをはるかに超え、したがってプラトンの三位一体を超えたものとなります。 したがって、三位一体は、神と人間の本質を理解する象徴としてそれ自体を明らかにします。 ケプゲン 14 章にあるように、それは「神の啓示であるだけでなく、同時に人間の啓示でもある」のです。

[240] 聖霊を母とするグノーシス派の解釈には、マリアが神の誕生の道具であり、したがって人間として三位一体のドラマに関与するようになったという真実の核心が含まれています。 したがって、神の母は、三位一体への人類の本質的な参加の象徴とみなすことができます。 この仮定の心理学的正当化は、もともと無意識の自己啓示にその源を持っていた思考が、意識の外部の力の現れであると感じられていたという事実にあります。 原始人は考えません。 という考えが彼に伝わってきます。 私たち自身も、特定の特に啓発的なアイデアを「影響力」や「インスピレーション」などとして今でも感じています。判断や洞察の閃きが無意識の活動によって伝達される場合、それらは多くの場合、元型的な女性像、アニマ、または最愛の母親に起因すると考えられます。 すると、あたかもそのインスピレーションが母親や愛する人、つまり「ファム・インスピラトリス」から来たかのように見えます。 このことを考慮すると、聖霊はご自身の中性的な呼称( )を女性的な呼称に交換する傾向があるでしょう。 (精神を意味するヘブライ語のルアハは主に女性名詞であることに注意してください。)聖霊とロゴスは、ソフィアのグノーシス主義の考えの中で融合し、また中世の自然哲学者のサピエンティアの中で融合します。ソフィアは彼女についてこう言いました。 「matris sedet sapientia patris」(父親の知恵は母親の膝の上にある)。 これらの心理的関係は、なぜ聖霊が母親として解釈されたのかを説明するものではありますが、聖霊そのものについての私たちの理解には何も加えません。母親の本来の立場が 2 番目であるときに、どうして母親が 3 番目になることができるのかを理解することは不可能だからです。 。

[241] 聖霊は反省の行為によって仮定された「生命」の仮説であるため、聖霊はその特異な性質により、別個の比較不能な「第三」として現れ、その特異性そのものが、聖霊が生命のどちらでもないことを証明している。 それは妥協ではなく、単なる三要素の付属物ではなく、むしろ父と子の間の緊張の論理的に予想外の解決です。 団結する「第三」を不合理に生み出すのはまさに人間の反省のプロセスであるという事実自体が、神が人間の領域に降臨し、人間が神の領域に登るという救済のドラマの性質と関係している。

A

[...]

[239] The nature of this conception (i.e., the hypostatizing of a quality) meets the need evinced by primitive thought to form a more or less abstract idea by endowing each individual quality with a concrete existence of its own. Just as the Holy Ghost is a legacy left to man, so, conversely, the concept of the Holy Ghost is something begotten by man and bears the stamp of its human progenitor. And just as Christ took on man’s bodily nature, so through the Holy Ghost man as a spiritual force is surreptitiously included in the mystery of the Trinity, thereby raising it far above the naturalistic level of the triad and thus beyond the Platonic triunity. The Trinity, therefore, discloses itself as a symbol that comprehends the essence of the divine and the human. It is, as Koepgen 14 says, “a revelation not only of God but at the same time of man.”

[240] The Gnostic interpretation of the Holy Ghost as the Mother contains a core of truth in that Mary was the instrument of God’s birth and so became involved in the trinitarian drama as a human being. The Mother of God can, therefore, be regarded as a symbol of mankind’s essential participation in the Trinity. The psychological justification for this assumption lies in the fact that thinking, which originally had its source in the self-revelations of the unconscious, was felt to be the manifestation of a power external to consciousness. The primitive does not think; the thoughts come to him. We ourselves still feel certain particularly enlightening ideas as “in-fluences,” “in-spirations,” etc. Where judgments and flashes of insight are transmitted by unconscious activity, they are often attributed to an archetypal feminine figure, the anima or motherbeloved. It then seems as if the inspiration came from the mother or from the beloved, the “femme inspiratrice.” In view of this, the Holy Ghost would have a tendency to exchange his neuter designation ( ) for a feminine one. (It may be noted that the Hebrew word for spirit—ruach— is predominantly feminine.) Holy Ghost and Logos merge in the Gnostic idea of Sophia, and again in the Sapientia of the medieval natural philosophers, who said of her: “In gremio matris sedet sapientia patris” (the wisdom of the father lies in the lap of the mother). These psychological relationships do something to explain why the Holy Ghost was interpreted as the mother, but they add nothing to our understanding of the Holy Ghost as such, because it is impossible to see how the mother could come third when her natural place would be second.

[241] Since the Holy Ghost is an hypostasis of “life,” posited by an act of reflection, he appears, on account of his peculiar nature, as a separate and incommensurable “third,” whose very peculiarities testify that it is neither a compromise nor a mere triadic appendage, but rather the logically unexpected resolution of tension between Father and Son. The fact that it is precisely a process of human reflection that irrationally creates the uniting “third” is itself connected with the nature of the drama of redemption, whereby God descends into the human realm and man mounts up to the realm of divinity.

[242] 三位一体の魔法陣で考えること、あるいは三位一体論的思考は、それが単なる想像の問題ではなく、計り知れない精神的な出来事を表現するという点において、実際には「聖霊」によって動機づけられています。 この思考を働かせる原動力は、意識的な動機ではありません。 それらは、「父から子への変化」、「統一性から二元性へ」、「無反省から批判へ」という表現以上に優れた、あるいはより簡潔な公式をほとんど見つけることができないような、あいまいな精神的状況に根ざした歴史的出来事から生じている。 三位一体的思考には個人的な動機が欠如しており、それを動機づける力が非個人的で集団的な精神状態に由来している限り、それはすべての個人的ニーズをはるかに超える無意識の精神のニーズを表しています。 この必要性は、人間の思考によって助けられ、三位一体のシンボルを生み出しました。それは、変化と精神的変容の時代における全体性の救いの公式として機能する運命にありました。 人間自身によって引き起こされたり、意識的に意志されたわけではない精神活動の現れは、それらが癒し、完全にするという意味で、悪魔的、神聖、または「神聖」であると常に感じられてきました。 彼の神についての考えは、無意識から生じるすべてのイメージと同じように機能します。つまり、その瞬間の一般的な気分や態度を補ったり完成させたりするものであり、人間が精神的な全体になるのは、これらの無意識のイメージの統合を通じてのみです。 すべてが自我である「単なる意識」の人は、無意識から離れて存在しているように見えるかぎり、単なる断片にすぎません。 しかし、無意識が分離すればするほど、それが意識の心に現れる形はさらに恐るべきものになります――神の形ではないにしても、執着と感情の爆発というより好ましくない形になります。 15 神は無意識の内容を擬人化したものであり、精神の無意識の活動を通して私たちに姿を現すからです。 16 三位一体論の考え方にも同様の性質があり、その情熱的な奥深さは、後発の私たちに素朴な驚きを呼び起こします。 人類の歴史におけるその大きな転換点によって魂のどのような深みが揺さぶられたのか、私たちはもはや知りません、あるいはまだ発見していません。 聖霊は人類に投げかけた問いに対する答えを見つけられずに消え去ったようです。

5. 4番目の問題

I. クォーターニティの概念

[243] 哲学用語で神の像の三位一体の公式を最初に提唱した『ティマイオス』は、「1、2、3 — しかし… 4 番目はどこですか?」という不気味な質問から始まります。 ご存知のとおり、この質問は再び取り上げられています[...]

~CG Jung、CW 11、心理学と宗教、東洋と西洋。

5. 4番目の問題

I. クォーターニティの概念

[243] 哲学用語で神の像の三位一体の公式を最初に提唱した『ティマイオス』は、「1、2、3 — しかし… 4 番目はどこですか?」という不気味な質問から始まります。 ご存知のとおり、この質問は再び取り上げられています[...]

~CG Jung、CW 11、心理学と宗教、東洋と西洋。

[242] Thinking in the magic circle of the Trinity, or trinitarian thinking, is in truth motivated by the “Holy Spirit” in so far as it is never a question of mere cogitation but of giving expression to imponderable psychic events. The driving forces that work themselves out in this thinking are not conscious motives; they spring from an historical occurrence rooted, in its turn, in those obscure psychic conditions for which one could hardly find a better or more succinct formula than the “change from father to son,” from unity to duality, from non-reflection to criticism. To the extent that personal motives are lacking in trinitarian thinking, and the forces motivating it derive from impersonal and collective psychic conditions, it expresses a need of the unconscious psyche far surpassing all personal needs. This need, aided by human thought, produced the symbol of the Trinity, which was destined to serve as a saving formula of wholeness in an epoch of change and psychic transformation. Manifestations of a psychic activity not caused or consciously willed by man himself have always been felt to be daemonic, divine, or “holy,” in the sense that they heal and make whole. His ideas of God behave as do all images arising out of the unconscious: they compensate or complete the general mood or attitude of the moment, and it is only through the integration of these unconscious images that a man becomes a psychic whole. The “merely conscious” man who is all ego is a mere fragment, in so far as he seems to exist apart from the unconscious. But the more the unconscious is split off, the more formidable the shape in which it appears to the conscious mind— if not in divine form, then in the more unfavourable form of obsessions and outbursts of affect. 15 Gods are personifications of unconscious contents, for they reveal themselves to us through the unconscious activity of the psyche. 16 Trinitarian thinking had something of the same quality, and its passionate profundity rouses in us latecomers a naïve astonishment. We no longer know, or have not yet discovered, what depths in the soul were stirred by that great turning-point in human history. The Holy Ghost seems to have faded away without having found the answer to the question he set humanity.

5. THE PROBLEM OF THE FOURTH

I. THE CONCEPT OF QUATERNITY

[243] The Timaeus, which was the first to propound a triadic formula for the God-image in philosophical terms, starts off with the ominous question: “One, two, three—but … where is the fourth?” This question is, as we know, taken up again [...]

~CG Jung, CW 11, Psychology and Religion, East and West.