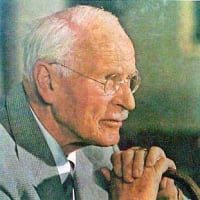

ユングの言葉はどこにありますか?

"人生は40歳からが本番だ。それまでは研究をしているだけだ。"

Where do I find Jung's quote: "Life really begins at forty. Up until then, you are just doing research."

A

質問3.人生の後半、つまり30歳を過ぎてからの神経症の治療は、人生の前半の治療とどのような点で異なるのでしょうか。

ユング博士 これもまた、何時間でも議論できる問題です。

私が詳細に説明することは不可能ですが、いくつかのヒントをお伝えすることはできます。

人生の前半、つまり最初の35~36年は、個人が世界に進出する時期だと私は考えています。

それはちょうど天体の爆発のようなもので、その破片は宇宙に飛び出し、ますます遠くまで広がっていきます。

そうして心の地平線が広がり、願望や期待、野心、世界を征服して生きようとする意志が、人生の半ばに至るまでどんどん広がっていくのです。

40年経っても、夢見ていた人生の地位に到達していない人は、簡単に失望の餌食になる。

それゆえ、40年目以降の不況は異常に多い。

それは決定的な瞬間であり、偉大な芸術家(例えばニーチェ)の生産性を研究すると、人生の後半の初めに、彼らの創造性のモードがしばしば変化することがわかります。

例えば、ニーチェは37歳から38歳のときに、それまでのすべての作品とはまったく異なる、彼の傑出した作品である『ツァラトゥストラ』を書き始めました。

それは重要な時期です。人生の後半になると、自分自身に疑問を持つようになります。

というか、そういう質問を避けていたのですが、自分の中の何かが質問してくるのです。

そして次に、"あなたは今どこに向かっているのか?"という声を聞くのが嫌なのです。

若い時には、ある位置まで来ると、"これが私の欲しいものだ "と思うものです。

ゴールは見えているようで見えていません。

人は、「結婚して、こういう地位に就いて、お金をたくさん稼いで、それから何をするかわからない」と考えます。

仮にそれに到達したとすると、次の質問が来る。"で、どうするの?

私たちは本当にこのままずっと同じことを続けることに興味があるのだろうか、それとも以前と同じくらい素晴らしい、あるいは魅力的なゴールを探しているのだろうか」。

その答えは、「この先には何もない」です。

先に何があるのか?

死が待っている」。

それは嫌ですよね。それは最も嫌なことです。

だから、人生の第二部には何の目標もないように見える。

その答えはわかっているはずだ。

太古の昔から、人間はその答えを持っています。"私たちは前を向いて、明確な終わりに向かって進んでいるのです」。

宗教は、ほら、偉大な宗教は、人生の後半の終わり、ゴールのために人生の後半を準備するためのシステムです。

ある時、私は友人の助けを借りて、私がアンケートの発案者であることを知らない人たちにアンケートを送りました。

私は、"なぜ人は神父に告白する代わりに医者に行くことを好むのか?

という質問を受けたことがありますが、本当に医者がいいのかどうか疑問に思っていたので、一般の人がどう答えるのか知りたかったのです。

たまたまそのアンケートが中国の人の手に渡り、彼の答えは「若い時は医者に、年を取ったら哲学者に」でした。

つまり、若いときには、世界を征服するような大らかな生き方をし、年をとると、反省し始めるという違いです。

自分のしてきたことを自然に考え始めるのです。

おそらく、何の面白みもない日曜日の朝、教会に行く代わりに、「さて、私は去年何をして生きてきたのだろう」などとふと考える瞬間が来る。

さて、人生の最初の部分、つまり性的な大冒険を広げることに対する抵抗がありますよね。

若い人たちが、自分の命を危険にさらすことや、社会的なキャリアを積むことに対して抵抗があると、それは集中力や努力が必要だからであり、彼らは神経症になりがちです。

人生の後半では、心の自然な発達、つまり反省や終わりへの準備を妨げている人たちが、神経症になるのである。

それが第二の人生の神経症である。

人生の第二部で性の抑圧があると言えば、このような抑圧がある場合が多く、これらの人々は人生の第一部で抵抗する人々と同じように神経症になります。

最初は人生に参加したくない、人生を危険にさらすのが怖い、人生のために健康や命を危険にさらすのが怖い、そして人生の第2部では時間がない。

A

Question 3. In what respect, if any, does the treatment of neurosis in the second half of life—that means after thirty—differ from that in the first half of life?

Dr. Jung: This is also a question which you could discuss for several hours.

It is quite impossible for me to go into details; I only can give you a few hints.

The first half of life, which I reckon lasts for the first 35 or 36 years, is the time when the individual usually expands into the world.

It is just like an exploding celestial body, and the fragments travel out into space, covering ever greater distances.

So our mental horizon widens out, and our wishes and expectation, our ambition, our will to conquer the world and live, go on expanding, until you come to the middle of life.

A man who after forty years has not reached that position in life which he had dreamed of is easily the prey of disappointment.

Hence the extraordinary frequency of depressions after the fortieth year.

It is the decisive moment; and when you study the productivity of great artists—for instance, Nietzsche—you find that at the beginning of the second half of life their modes of creativeness often change.

For instance, Nietzsche began to write Zarathustra, which is his outstanding work, quite different from everything he did before and after, when he was between 37 and 38.

That is the critical time. In the second part of life you begin to question yourself.

Or rather, you don’t; you avoid such questions, but something in yourself asks them, and you do not like to hear that voice asking “What is the goal?”

And next, “Where are you going now?”

When you are young you think, when you get to a certain position, “This is the thing I want.”

The goal seems to be quite visible.

People think, “I am going to marry, and then I shall get into such and such a position, and then I shall make a lot of money, and then I don’t know what.”

Suppose they have reached it; then comes another question: “And now what?

Are we really interested in going on like this forever, for ever doing the same thing, or are we looking for a goal as splendid or as fascinating as we had it before?”

Then the answer is: “Well, there is nothing ahead.

What is there ahead?

Death is ahead.”

That is disagreeable, you see; that is most disagreeable.

So it looks as if the second part of life has no goal whatever.

Now you know the answer to that.

From time immemorial man has had the answer: “Well, death is a goal; we are looking forward, we are working forward to a definite end.”

The religions, you see, the great religions, are systems for preparing the second half of life for the end, the goal, of the second part of life.

Once, through the help of friends, I sent a questionnaire to people who did not know that I was the originator of the questionnaire.

I had been asked the question, “Why do people prefer to go to the doctor instead of to the priest for confession?”

Now I doubted whether it was really true that people prefer a doctor, and I wanted to know what the general public was going to say.

By chance that questionnaire came into the hands of a Chinaman, and his answer was, “When I am young I go to the doctor, and when I am old I go to the philosopher.”

You see, that characterizes the difference: when you are young, you live expansively, you conquer the world; and when you grow old, you begin to reflect.

You naturally begin to think of what you have done.

There a moment comes, between 36 and 40—certain people take a bit longer—when perhaps, on an uninteresting Sunday morning, instead of going to church, you suddenly think, “Now what have I lived last year?” or something like that; and then it begins to dawn, and usually you catch your breath and don’t go on thinking because it is disagreeable.

Now, you see, there is a resistance against the widening out in the first part of life—that great sexual adventure.

When young people have resistance against risking their life, or against their social career, because it needs some concentration, some exertion, they are apt to get neurotic.

In the second part of life those people who funk the natural development of the mind—reflection, preparation for the end—they get neurotic too.

Those are the neuroses of the second part of life.

When you speak of a repression of sexuality in the second part of life, you often have a repression of this, and these people are just as neurotic as those who resist life during the first part.

As a matter of fact it is the same people: first they don’t want to get into life, they are afraid to risk their life, to risk their health, perhaps, or their life for the sake of life, and in the second part of life they have no time.

つまり、私が人生の後半を締めくくるゴールについて語るとき、人生の前半と後半では、どれだけ治療法を変えなければならないかということがわかります。

今まで語られてこなかった問題が出てきます。

ですから、私は大人のための学校を強く提唱します。

あなた方は、人生に対して非常によく準備されていたと思います。

とても立派な学校があり、立派な大学があり、これらはすべて人生の拡大のための準備です。

しかし、大人のための学校はどこにあるのでしょうか?40歳、45歳、人生の第2ステージに入った人たちのための学校です。

ありません。

それはタブーで、話してはいけません。

だからこそ、彼らは素敵な更年期の神経症や精神病になってしまうのです。

~カール・ユング『C.G.ユング、語る。Interview and Encounters, Pages 106-108.

A

人生の後半になると、人は内なる世界と知り合うようになります。これは一般的な問題である。~カール・ユング『手紙』第2巻、402ページ。

So, you see, when I speak of the goal which marks the end of the second half of life, you get an idea of how far the treatment in the first half of life, and in the second half of life, must needs be different.

You get a problem to deal with which has not been talked of before.

Therefore I strongly advocate schools for adult people.

You know, you were fabulously well prepared for life.

We have very decent schools, we have fine universities and that is all preparation for the expansion of life.

But where have you got the schools for adult people? for people who are 40, 45, about the second part of life?

Nothing.

That is taboo; you must not talk of it; it is not healthy.

And that is how they get into these nice climacteric neuroses and psychoses.

~Carl Jung, C.G. Jung Speaking: Interviews and Encounters, Pages 106-108.

A

In the second half of life one should begin to get acquainted with the inner world. That is a general problem. ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. II, Page 402.