次に、「Liber Secundus」の中でも最も悲惨なエピソードとして、ユングは暗い沼地のような、蛇が出没する荒れ地にいることに気づきます。 見下ろすと、頭蓋骨が一部潰れて血まみれになった子供の死体がありました。 覆いを被った女性が、その子の肝臓を食べるように命じます。 ユングはこの提案と状況に憤りを感じますが、女性が「自分は子供の魂だ」と言うと、従わざるを得ませんでした。 しかし、女性が自分は子供の魂だと言うと、従わざるを得なくなります。嫌気がさした彼は不気味な儀式を実行しますが、女性はベールを脱ぎ、自分は本当にユングの魂だと告げます。 ユングはこのビジョンを解釈し、子供はまさに神のイメージであると指摘します。 彼は、神を象徴的に殺すことができたときに、人は人間性を取り戻すことを暗示しています。つまり、神への極端な信仰によって自分のインフレーションを補うことができるのです。 実際、歴史的にも宗教的にも、神の名のもとに、神の意志によって行動していると主張する人々によって、多くの残虐行為が行われてきました。 ユングはここで、そのようなインフレーションが魂を弱らせ、破壊し、仲間の苦しみを感じ、共感する能力を失わせることを示唆しているようです。 神に投影された精神的エネルギーを取り戻し、自分の人生を取り戻すためには、神を犠牲にしなければなりません。 そのためには、人間が原型へのインフレーション(神への憑依)から抜け出すための、ある種の「悪」が必要だとユングは主張します。 そのための手段として、ユングは聖体拝領の儀式を挙げています。救世主の肉を食べ、その血を飲むことで魂が癒されるというミサの儀式です。 ある意味では、聖体拝領の儀式において、全知全能の存在としてのイエスのイメージが殺害されることを暗示しているのです(ちょうど、あまりにも人間的な苦しみを受けるイエスのイメージが強調されるように)。 皮肉なことに、この暴力的で野蛮とも思えるエピソードの中で、ユングは失われた人間性の一部を取り戻したように見える。 重要なのは、彼の魂が、この象徴的な行為、つまり犠牲と交わりの内的な儀式を実行するように求めていることです。

その後、「第二紀の書」では別の犠牲の行為が行われ、ユングが感情や感覚の機能を発達させる必要があることを示しています。 この時、深淵からカビリ族が現れます。 古代ギリシャに伝わるヌーメのような神々で、ユングは彼らが地中からやってくると表現しています。 船乗りを守り、豊穣をもたらすカビーリは、創造的なアイデアや意識を供給することで知られていましたが、グレムリンのように意識を妨害することもありました。 カビリは、ユングが自分たちの主人になったが、自分たちの領域である生命体をコントロールできると錯覚してはならないと発表しています。 カビリ族は、生命体や創造性はゆっくりと自力で発生するものであり、知性や意志によって「引き上げる」ことはできないと言います。 カビリ族は、彼のために作った剣を渡し、それが狂気を克服する手段だと言う。 彼らは彼が大きな結び目に絡まっていると言い、ユングはそれを見ることを要求します。 彼らは彼に自分の脳を見せ、彼があまりにも複雑に絡み合い、夢中になっていると言います。 自分の脳に夢中になっていることが、彼の狂気の源なのです。 カビリは互いに積み重なり、繊維、根、運河を作っていると表現されています。 彼らは、自分たちはまさにユングの脳であり、ユングは彼らを剣で切り捨てなければならないと言う。 そうすれば、それらは引き上げられ、彼を通して生きるようになる(つまり、統合される)。 ユングは彼らの望み通りに行動します。 ユングは次に、カビリ族が建てた大きな塔について説明しています。彼らは人間の思考ではなく、内臓のエネルギーでその塔を建てたと言います。 その塔は強固であり、自分自身から生きている者の象徴であると述べています。

Next, in perhaps the most harrowing episode in Liber Secundus, Jung finds himself in a dark, swampy, serpent infested wasteland. Looking down, he sees a dead child, her skull partially crushed and bloodied. A shrouded woman commands him to eat the child’s liver. Repulsed, Jung is outraged at the suggestion and at the entire situation, but when the woman says she is the soul of the child, he feels compelled to obey her. Disgusted, he carries out the macabre ritual only to have the woman lift her veil and announce that she is really Jung’s soul. Jung interprets the vision, noting that the child is really the image of God. He implies that one regains one’s humanity when one is able to symbolically slay one’s God—i.e., compensate for one’s inflation with an extreme faith in God. Indeed, many atrocities throughout history and across religions have been carried out by those who claimed to be acting in the name, and through the will, of their god. Jung seems to imply here that such inflation weakens and destroys the soul, one’s capacity to feel and empathize with the suffering of one’s fellow beings. The god must be sacrificed in order to re-claim the psychic energy projected onto it and re-claim his own life. To do this, Jung asserts, a particular type of “evil” is necessary for men to break free of inflation with an archetype (possession by a god). Jung cites the ritual of communion as a means to this end, the eating of the Savior’s flesh and drinking of his blood healing the soul in the ritual of the mass. In a sense, he implies that in the ritual of communion, the image of Jesus as an all-powerful, omniscient and omnipotent being is slain (just as the image of the all-too-human suffering Jesus is emphasized). Ironically, in this violent and seemingly barbaric episode, Jung seems to regain some of his lost humanity. Significantly, it is his soul that asks him to carry out this symbolic act of his own, inner ritual of sacrifice and communion.

Later in Liber Secundus, another act of sacrifice takes place illustrating Jung’s need to develop his feeling and sensation functions. At this point the Cabiri emerge from the depths. They are gnome-like deities from ancient Greece, and Jung describes them as coming from under the earth. Protecting sailors and promoting fertility, the Cabiri were known to supply creative ideas and consciousness but could also interfere with consciousness at times, like gremlins. The Cabiri announce that Jung is now their master but that he should not delude himself that he can control living matter, which is their realm. They say that living matter and creativity emerges on its own, slowly, and cannot be “pulled up” by the intellect and will. The Cabiri give him a sword they have made for him and tell him it is the means of overcoming his madness. They say he is entangled in a great knot, which Jung demands to see. They show him his own brain, in which they say he is too entangled and engrossed. Being lost in his own brain is the source of his madness. The Cabiri are described as piling up on one another, creating fibers, roots and canals—an image of a brain! They say they are indeed Jung’s brain and he must cut them down with a sword. If he does this, they will be pulled up and live through him (i.e., be integrated). He does as they wish. Jung then describes a great tower which was built by the Cabiri; he says they built it from the energy of the guts, not from human thoughts. He says it is solid and the symbol of one who lives from himself.

リベール・セクンドゥス」の最後に、ユングの魂が現れ、彼は仕事を続けることができずに塞ぎ込んでしまったことを彼女に伝えます。 すると彼女は、自分の野心が邪魔をしているのだと答え、あるおとぎ話を聞かせてくれました。 それは、子供のいない王様が息子を欲しがっているというもの。 彼は魔女を訪ね、まるで司祭のように告白する。 魔女は「恥じるべきだ」と言うが、彼を助ける。 彼は庭にカワウソのラードの入った鍋を埋めると、9ヶ月後には子供、つまり息子が生まれる。 息子は強く賢く成長するが、いつか父親に取って代わろうとする。 自分の傲慢さにショックを受けた父親は、再び魔女のもとを訪れ、アドバイスを求めます。 今度は、カワウソのラードを別の鍋に植え、9ヶ月後に息子は死んでしまいます。 父親は息子を埋葬しますが、ひどい後悔の念に襲われます。 王様は3度目に魔女を訪ね、今度はラッコの壺を埋めると、9ヶ月後には幼い息子が戻ってきました。 少年は魔法のようにすくすくと成長し、すぐにまた父の王座を欲しがります。 今度は父がそれに応じ、王となった息子は父の面倒を一生見ることになります。 ユングは自分の魂におとぎ話の意味を尋ねます。 彼女は、自分は王であり、息子は愛よりも命を重んじる疑心暗鬼の思考であると答えます。 魔女はユングにとって母親であり、ユングが新たな態度を育もうとするならば、母親の子供として服従しなければなりません。 ユングは母親の子どもになることに抵抗し、それが自分の男らしさや自律の計画を脅かすものだと考えます。 魂は、だからこそ、自分の野心の解毒剤として母に服従しなければならないと言います。 ユングは彼女の忠告を受け、おとぎ話の世界に入り込み、すべての権力を息子に譲り、心の平穏を得ます。 ユングは抵抗と恐怖を感じながらも、それが自分を癒すことになると知っていたのです。

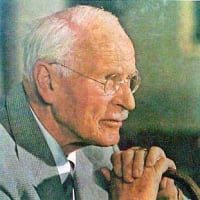

この時点でユングは、この旅を始めたのは、自分自身と共存できなかったからだと考えています。 自分自身」(自分がなった人間)が嫌で嫌でたまらず、一緒に暮らせる人間に変身するためには、ある種の「中世」に戻らなければならなかったのです。 地獄に落ちて自分を変えなければならない、それが道であると主張する。 赤い本』の最終章「スクルチニー」で、ユングはこの「共に生きる人間になる」という考えを展開しています。 ユングはまず、目覚めている自分の人格、つまり「私」という人格を執拗に批判し、その欠点や失敗を詳細に列挙し、拷問や罰で脅して、自分の悪癖や他人を傷つける傾向を自覚させようとします。 彼は自分の「私」を、傲慢、独善的、野心的、過敏、不信、執念深いと表現しています。 このような野蛮な「私」には、このような野蛮な手段が必要なのだとユングは主張しています。

その後、『スクルチニー』では、ある夜遅くにユングの魂が彼を訪れます。 やがて、彼の家のドアがノックされました。 死者は生者以上に何も知らず、満たされない人生の完成、解決、救済を求めているのだとユングは指摘します。 ユングは、このエピソードに対する自分の魂の解釈を信じることができないのではないかと不安になります。幸運にもその時、フィレモンが現れ、死者に向けて説教を始めます。彼は「良いもの、美しいもの」を持ってきて、死者への説教の前に、ユングの魂への疑念を強めます。"魂を恐れ、軽蔑し、愛する、神々のように。 神々のように、魂を恐れ、軽蔑し、愛し、我々から遠く離れていますように。 しかし何よりも、決して失ってはならない。 愛と恐怖と軽蔑と憎しみをもって魂にしがみつき、目を離さないことだ。 彼女は、鉄の壁の後ろ、最も深い金庫に保管されるべき地獄の神の宝なのだ」(343ページ)。

Near the end of Liber Secundus, Jung’s soul appears and he tells her that he has felt blocked, unable to continue with his work. She replies that it is his own ambition that is blocking him and tells him a fairy tale. In it, a king has no children and desires a son. He visits a witch and confesses to her as if she were a priest. She says he should be ashamed but helps him. He buries a pot of otter lard in his garden and in nine months a child, a son, emerges. The son grows up strong and smart, but wants one day to replace his father. Shocked at his arrogance, the father visits the witch again for advice. This time, he plants another pot of otter lard and in nine months the son dies. He buries his son but feels terrible remorse. The king then visits the witch a third time; this time, he buries the pot of otter lard and in nine months has his infant son back again. The boy grows magically fast and soon again desires his father’s throne. This time, the father complies, and the son, now king, takes care of his father for the rest of his life. Jung asks his soul the meaning of the fairy tale. She replies that he is the king and his son is the doubting thought that valued life over love. The witch is the mother to whom Jung must submit as her child if he wishes to nurture a new attitude, for only the mother can create. Jung resists becoming a child to the mother and sees this as threatening his manhood and his plans of autonomy. The soul says this is precisely why he must subject himself to her, as an antidote to his own ambition. Jung takes her advice and lives out the fairy tale, giving over all power to his son and in so doing finds some peace of mind. He does this with resistance and fear, but knows it will heal him.

At this point, Jung reflects that he began this entire journey because he could not live with himself. His “self” (the person he had become) was detestable to him, and he had to return to a type of “middle ages” in order to transform himself into someone he could live with. He needed to go down into hell and transform himself—this, he asserts, is the way. In the final section of The Red Book, called Scrutinies, Jung develops this idea of becoming a person he can live with. He begins by relentlessly criticizing his own waking personality, or “I” personality, enumerating in detail all of its shortcomings and failures and threatening it with torture and punishment, seeking to make it more aware of its own vices and tendencies to hurt others. He describes his “I” as arrogant, self-righteous, ambitious, overly sensitive, mistrustful, and vindictive. Such barbaric means are necessary, Jung asserts, for such a barbaric “I” which has made virtually no progress since “the early Middle ages” (p. 333).

Later in Scrutinies, Jung’s soul visits him late one night. Soon, there is a knock at his door. It is an enormous crowd of the dead; Jung notes that the dead know no more than the living and seek completion, resolution, redemption for their unfulfilled lives. Jung fears that he can’t trust his soul’s interpretation of this episode; luckily, Philemon shows up just then and proceeds to preach to the dead. He brings with him “the good and the beautiful” and before preaching to the dead, he reinforces Jung’s suspicion of the soul: “Fear the soul, despise her, love her, just like the Gods. May they be far from us! But above all, never lose them! Because when lost they are as malicious as the serpent…Cling to the soul with love, fear, contempt, and hate, and don’t let her out of your sight. She is a hellish-divine treasure to be kept behind walls of iron and in the deepest vault” (p. 343).

魂の再発見という中心テーマのいくつかの側面が、この長くて複雑なシークエンスに存在しています。 Scrutinies』の第1部で痛烈な自己批判をした後なら、ユングはもっと思いやりを持ち、自分の魂との関係を築くことに前向きになるだろうと思うかもしれません。 しかし、そうではありません。 まず、ユングの魂への扱いが異常に厳しいように感じられます。 ユングが魂とどのように関わっていくべきかというフィレモンの教えは、アニマの投影に対する警告と受け取れるかもしれませんが(Schwartz-Salant, p.30)、ユングがいまだにアニマに対して極度の不信感を抱いているという事実は、どうしても理解できません。 彼女は「鉄の壁の向こう、最も深い地下室に保管されるべき地獄の神の宝」なのです。 ユングが冒険を始めて以来、愛することを拒んできたサロメと結びついた彼女は、どこまでも否定的で疑わしいファム・ファタールのままです。 さらに、彼の魂は、死者との出会いのエピソードを導く人物ではなく、フィレモンなのです。 これを、『オデュッセイア』でオデュッセウスに死者の呼び方や交流の仕方を指南したシーリスの役割や、『地獄篇』でヴァージルにダンテの姿を見せるよう指示して送ったベアトリーチェの役割と対比してみましょう。 これらのいずれの場合も、アニマは死者(無意識)との関係を確立し、発展させるという積極的な道具的役割を担っています。 ユングの場合は、アニマにこの仕事を任せていないようですし、アニマが非常に信頼できる存在であるように見せてもいません。 ユングはフィレモンを過度に強調し、オヴィッドの「メタモルフォーゼ」とゲーテの「ファウストII」の両方に出てくるフィレモン神話を使用して、彼と彼の妻であるバウシスの両方の性格を歪めています。

一般的に『赤い本』では、ユングの女性的なものに対する態度には深刻な問題があるように思われます。 バウシスの例を挙げていますが、彼女はこの尊敬すべき夫婦の片割れとしての正当な尊厳と高潔さを持っているのではなく、「フィレモンの片割れ」に過ぎないとされています。 ユングはこの神話の第一の特徴である夫婦の献身と貞節を無視し、フィレモンの混沌(洪水)からの生還との関連性を利用している。 彼は、フィレモンが大惨事を生き延びるために必要だからといって、バウシスをあっさりと退け、二人が夫婦として生き延びたのはお互いへの深い愛情があったからだという事実を無視しています。 その代わり、ユングはバウシスを「地獄に向かって努力する者」、フィレモンを「善に向かって努力する者」と分けています。 これは女性性と悪との昔からのつながりであり、彼がサロメを認識する方法や、後に「女性の神秘」に対する反応でさらに特徴づけられる。 (Schwartz-Salant, p. 26)

フィレモンは今、毎晩訪れる死者たちに7つの説教をしている。 彼は、スピリチュアリティにセックスを取り入れることの重要性などを含むグノーシス的な教えを提供する。 説教の最後にイエスが現れ、フィレモンはユングに、イエスが自分のためにしてくれたように、自分も個性化の道のために犠牲にならなければならない、それがイエスのメッセージを解釈し、従う正しい方法だと強調します。 その後、ユングはフィレモンの庭を訪れ、イエスもフィレモンの客の一人として庭に到着していることを知ります。 フィレモンはイエスを歓迎し、自分の兄弟(サタン)がすでに来ていると言います。2人は蛇を介して多くの共通点があり、切っても切れない関係にあることを指摘します。 フィレモンは、自分の庭にイエスが必要だと言い、どんな贈り物を持ってきたのかと尋ねる。 イエスは「苦しみと犠牲の美しさ」と答えます(p.359)。

この『赤い本』の結末で注目すべきなのは、フィレモンが死者に説く複雑で難解なグノーシスの教えだけでなく、フィレモンの庭にないものもあるということだ。 ユングは悪魔や悪の必要性を説いたサロメの教えに価値を見出しているが、彼女や女性的なものを自分の庭に入れる必要性については考えていないようだ。 ユング、フィレモン、イエス、サタンは登場するが、サロメやバウシスなどの代表的な女性像は登場しない。 また、イエスの最後のメッセージである「苦しみと犠牲の美」は、自分の個性化に悩む人々に当てはまるように見えますが、イエスの教えの主要な側面である「思いやり」は含まれていません。 不思議なことに、ユングは後にカトリック教会の聖母マリアの受胎教義を称賛して女性性を含める必要性を認識しますが(MDR, p.202)、『赤い本』ではアニマは救済されないままです。

赤い本』の後、ユングがアニマを完全に統合し、発展させることに成功したかどうかは、依然として議論の対象となっています。 しかし、少なくとも「赤い本」完成後の後半生には、ある程度の進歩があったことは確かなようです。 晩年に書かれた自叙伝の中で、ユングはこう述べています。

Several aspects of the central theme of re-finding the soul are present in this long and complex sequence. One might think that after the scathing self-criticism of the first part of Scrutinies, Jung would be more compassionate and more open to building a relationship with his soul. But this is not the case. First, Jung’s treatment of the soul seems unusually harsh. Although Philemon’s teaching about how Jung should relate to the soul might be taken as his warning about projection of the anima (Schwartz-Salant, p. 30), one cannot quite get past the fact that Jung still holds extreme distrust toward her. She is “a hellish-divine treasure to be kept behind walls of iron and in the deepest vault.” For all intents and purposes, she remains a negative, suspicious femme fatale associated with Salome, whom Jung has refused to love since the start of his adventure. Moreover, his soul is not the figure to guide him through the episode of his encounter with the dead; rather, it is Philemon. Contrast this with Circe’s role in instructing Odysseus on how to summon and interact with the dead in The Odyssey or Beatrice instructing and sending Virgil to see Dante through the Inferno. In each of these cases, the anima is in the positive instrumental role of establishing and developing a relationship to the dead (the unconscious). In Jung’s case, he does not seem to trust his anima with this task, nor does he present her as being very trustworthy. Jung’s overemphasis on Philemon and his use of the Philemon myth from both Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Goethe’s Faust II distorts both his character and that of Baucis, his wife:

In general, The Red Book, there seems to be a serious problem with Jung’s attitude toward the feminine. The example of Baucis, being reduced to only “Philemon’s other half…” instead of her having her own rightful dignity and integrity as the proper half of this revered couple has been cited. Jung ignores the primary feature of the myth—marital devotion and fidelity—dropping it to use Philemon’s association to survival of chaos (the flood). He summarily dismisses Baucis because he needs Philemon’s connection to surviving catastrophe, ignoring the fact that they survived as a couple because of their deep love for each other. Instead, Jung splits them up referring to Baucis as the half that “strives to Hell,” while Philemon strives “toward the good.” This is the age-old connection of the feminine with evil, further characterized in the way he perceives Salome, and later in his reaction to the Feminine Mysteries. (Schwartz-Salant, p. 26)

Philemon now preaches his seven sermons to the dead who visit each night. He provides gnostic teachings that include the importance of incorporating sex with spirituality, etc. At the end of his teaching, Jesus appears and Philemon stresses to Jung that he must sacrifice for his own path of individuation as Jesus did for his—that is the proper way to interpret and follow Jesus’ message. Jung later visits Philemon in his garden and finds that Jesus has also arrived at the garden as one of Philemon’s guests. Philemon welcomes Jesus and says his brother (Satan) is already there; he notes that the two have much in common via the serpent and are inseparable. Philemon says he needs Jesus in his garden and asks what gift he has brought. Jesus replies, “the beauty of suffering and sacrifice” (p. 359).

What seems remarkable about this conclusion to The Red Book is not only the complex, esoteric gnostic teachings that Philemon preaches to the dead; but also what is absent from Philemon’s garden. Jung finds some value in Salome’s teaching about the necessity of the devil and of evil, but he does not seem to consider the necessity of including her, or the feminine, in his garden. Jung, Philemon, Jesus and Satan are present, but not Salome, Baucis or any representative female figure. And Jesus’ final message regarding “the beauty of suffering and sacrifice,” apparently applicable to those struggling with their own individuation, does not include compassion, a major aspect of Jesus’ teaching that seems to be applicable and necessary as well to Jung’s belief in individuation. Curiously, Jung would later recognize the need to include the feminine in his praise of the Catholic Church’s dogma of the assumption of the Virgin Mary (MDR, p. 202), but in The Red Book, the anima remains unredeemed.

Whether or not Jung, after The Red Book years, ever succeeded in fully integrating and developing his anima remains a subject of debate. At the very least, it seems clear that he made some progress in the second half of his life following the completion of The Red Book. In his autobiography, composed near the end of his life, Jung commented:

"しかし、アニマには良い面もあります。 無意識のイメージを意識に伝えるのがアニマであり、それが私が最も大切にしていることである。 私は何十年もの間、自分の感情の動きが乱れ、無意識の中で何かが起こっていると感じたとき、いつもアニマに相談していました。 そして、アニマにこう尋ねるのです。 何が見えますか? 私はそれを知りたい」と尋ねた。 多少の抵抗の後、彼女は定期的にイメージを作り出す。 イメージが出てくると同時に、不安や抑圧感は消えていった。 これらの感情の全体的なエネルギーは、画像への興味と好奇心に変換されました。 私は、アニマが私に伝えてくれたイメージについて、アニマに話しかけた。 (MDR, p. 187-188)

さらにユングは、アニマと彼女がもたらすイメージに対処する責任を強く意識していたようです。

"実験の結果、感情の背後にある特定のイメージを発見することが、治療の観点からどれほど役立つかを学びました......本質的なことは、これらの無意識の内容を擬人化することによって自分を区別し、同時に意識との関係に持ち込むことです。 それが、無意識の内容から力を奪うテクニックなのです。私は、自分の心の中にあるすべてのイメージ、すべての項目を理解しようと、細心の注意を払いました。 そして何よりも、それらを実際の生活の中で実現することに努めました。それは、私たちが普段怠っていることです。 私たちは、イメージを浮かび上がらせ、それについて疑問を抱くかもしれませんが、それだけです。 倫理的な結論を導き出すことはおろか、それを理解するための努力もしない。 この寸止めは、無意識の負の効果を想起させる」。(MDR, p. 177-192)

晩年のユングは、妻のエマ・ユングと再び親しくなり、彼女が聖杯を研究しているのを励ましていたようです。 ユングは聖杯について長い分析をすることはなかったが、エマとマリー・ルイーズ・フォン・フランツが聖杯についての本を作り、ユングの視点から聖杯を徹底的に分析し、高い評価を受けた。 おそらく「赤い本」は、ユングの精神に、ヒーローへの憧れから脱却してアニマにもっと時間を割くようにという警鐘を鳴らす役割を果たしたのではないでしょうか。 この本が書かれた当時、私たちはユングの変遷をつぶさに見ることができます。それは、彼が後にフィレモンの擬人化として知られるようになった慈悲深い賢明な老人にはまだ成熟しておらず、自分自身の魂を見つけて発展させるために自分自身に対する大きな実験に奮闘している中年男性の姿でした。

引用文献

ベアー、ディアドラ。 ユング: A Biography. ボストン。リトル・アンド・ブラウン社、2003年

ビービー、ジョン。 "The Red Book as a Work of Conscience". Quadrant 40.2 (Summer 2010). 41 -58.

コーベット、サラ "The Holy Grail of the Unconscious". The New York Times Magazine. 16 September 2009. 1-10. Web.

Furlotti, Nancy. Interview with David Van Nuys. Shrink Rap Radio. 242号。 23 July 2010. ポッドキャスト。

ユング、C.G. Memories, Dreams, Reflections. ニューヨーク。ヴィンテージ社、1989年

ユング、C.G. The Red Book. New York: W.W.Norton & Co., 2009.

ムーア、トーマス。 ケア・オブ・ザ・ソウル. New York: Harper Perennial, 1994.

Schwartz-Salant, Nathan. "混沌を見た者の印: A Review of C.G. Jung's Red Book.". Quadrant 40.2 (Summer 2010). 11-38.

Shamdasani, Sonu. "Liber Novus: The 'Red Book' of C.G. Jung.". Introduction. The Red Book. C.G.ユング著. New York: W.W.Norton & Co., 2009. 193-222.

ウォーカー、スティーブン。 ユングと神話をめぐるユング派。 ロンドン。ラウトレッジ、2002年

ユング・ブッククラブ(新)への参加はこちらから

FacebookTwitterEmail共有

“But the anima has a positive aspect as well. It is she who communicates the images of the unconscious to the conscious mind, and that is what I chiefly valued her for. For decades I always turned to the anima when I felt that my emotional behavior was disturbed, and that something had been constellated in the unconscious. I would then ask the anima: “Now what are you up to? What do you see? I should like to know.” After some resistance she regularly produced an image. As soon as the image was there, the unrest or the sense of oppression vanished. The whole energy of these emotions was transformed into interest in and curiosity about the image. I would speak to the anima about the images she communicated to me, for I had to try to understand them as best I could, just like a dream.” (MDR, p. 187-188)

Moreover, Jung seemed to be keenly aware of his responsibility to deal with the anima and the images she introduced:

“As a result of my experiment I learned how helpful it can be, from the therapeutic point of view, to find the particular images which lie behind the emotions…The essential thing is to differentiate oneself from these unconscious contents by personifying them, and at the same time to bring them into relationship with consciousness. That is the technique for stripping them of their power…I took great care to try to understand every single image, every item of my psychic inventory, …and, above all, to realize them in actual life. That is what we usually neglect to do. We allow the images to rise up, and maybe we wonder about them, but that is all. We do not take the trouble to understand them, let alone draw ethical conclusions from them. This stopping-short conjures up the negative effects of the unconscious.” (MDR, p. 177-192)

There seems to be some evidence that Jung took his own advice to heart to some degree and that he matured in his capacity for relationship and feeling, for in his later years, he seems to have drawn closer to Emma Jung, his wife, once again, encouraging her in her own studies of the Holy Grail—a subject he forfeited in deference to her interest and work (Bair, p. 429). Jung never devoted a lengthy analysis to the Grail, allowing Emma and Marie Louise Von Franz to produce a book on the subject, a critically acclaimed, in-depth analysis of the Grail from the Jungian perspective. Perhaps The Red Book served in part as a wake-up call from Jung’s psyche to break from his hero inflation and devote more time to the anima. At the time of its composition, we get an in-depth view of Jung in transition, not yet matured into the benevolent wise old man, the personification of Philemon that he came to be known as, but a middle-aged man struggling in his great experiment upon himself to find and develop his own soul.

Works Cited

Bair, Deirdre. Jung: A Biography. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 2003.

Beebe, John. “The Red Book as a Work of Conscience.” Quadrant 40.2 (Summer 2010). 41 -58.

Corbett, Sara. “The Holy Grail of the Unconscious.” The New York Times Magazine. 16 September 2009. 1-10. Web.

Furlotti, Nancy. Interview with David Van Nuys. Shrink Rap Radio. No. 242. 23 July 2010. Podcast.

Jung, C.G. Memories, Dreams, Reflections. New York: Vintage, 1989.

Jung, C.G. The Red Book. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2009.

Moore, Thomas. Care of the Soul. New York: Harper Perennial, 1994.

Schwartz-Salant, Nathan. “The Mark of One Who Has Seen Chaos: A Review of C.G. Jung’s Red Book.” Quadrant 40.2 (Summer 2010). 11-38.

Shamdasani, Sonu. “Liber Novus: The ‘Red Book’ of C.G. Jung.” Introduction. The Red Book. By C.G. Jung. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2009. 193-222.

Walker, Steven. Jung and the Jungians on Myth. London: Routledge, 2002.

Click here to join the (new) Jungian Book Club

FacebookTwitterEmail共有

最新の画像[もっと見る]

-

ユング心理学研究会

6ヶ月前

ユング心理学研究会

6ヶ月前

-

ユング心理学研究会

6ヶ月前

ユング心理学研究会

6ヶ月前

-

ユング心理学研究会

6ヶ月前

ユング心理学研究会

6ヶ月前

-

街録ch沖縄トークライブ!【那覇市/2024年7月28日】

6ヶ月前

街録ch沖縄トークライブ!【那覇市/2024年7月28日】

6ヶ月前

-

「汝自身を知る」とは「ダイモンを知る」ことを意味します。

8ヶ月前

「汝自身を知る」とは「ダイモンを知る」ことを意味します。

8ヶ月前

-

ユング心理学研究会

8ヶ月前

ユング心理学研究会

8ヶ月前

-

バーバラ・ハンナ: 全体性を目指して努力する。

8ヶ月前

バーバラ・ハンナ: 全体性を目指して努力する。

8ヶ月前

-

【プロが教える】たった1分でネット速度を快適にする裏技を紹介!【超便利】

8ヶ月前

【プロが教える】たった1分でネット速度を快適にする裏技を紹介!【超便利】

8ヶ月前

-

マーク・ザッカーバーグ/AI ニュース

9ヶ月前

マーク・ザッカーバーグ/AI ニュース

9ヶ月前

-

バーバラ・ハンナ: 全体性を目指して努力する。

9ヶ月前

バーバラ・ハンナ: 全体性を目指して努力する。

9ヶ月前