MADE IN JAPAN

When I visited Chernobyl for the first time 7 years ago, I didn’t think that a similar disaster could take place anywhere ever again, and certainly not in Japan. After all, nuclear power is safe and the technology is less and less prone to failure, and therefore a similar disaster cannot happen in the future. Scientists said this, firms that build nuclear power stations said this, and the government said this.

But it did happen.

When I was planning my trip to Fukushima I didn’t know what to expect. There the language, culture, traditions and customs are different, and what would I find there four years after the accident? Would it be something similar to Chernobyl?

THE DISASTER

This photographic documentary is not intended to tell the story of the events surrounding the disaster yet again. Like the incident that occurred on 26 April 1986, most readers know the story well. It is worth mentioning one very important aspect, however, which is an essential issue as we consider the story further. It is not earthquakes or tsunami that are to blame for the disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power station, but humans. The report produced by the Japanese parliamentary committee investigating the disaster leaves no doubt about this. The disaster could have been forseen and prevented. As in the Chernobyl case, it was a human, not technology, that was mainly responsible for the disaster.

As will be seen shortly, the two disasters have much more in common.

RADIATION OR EVACUATION

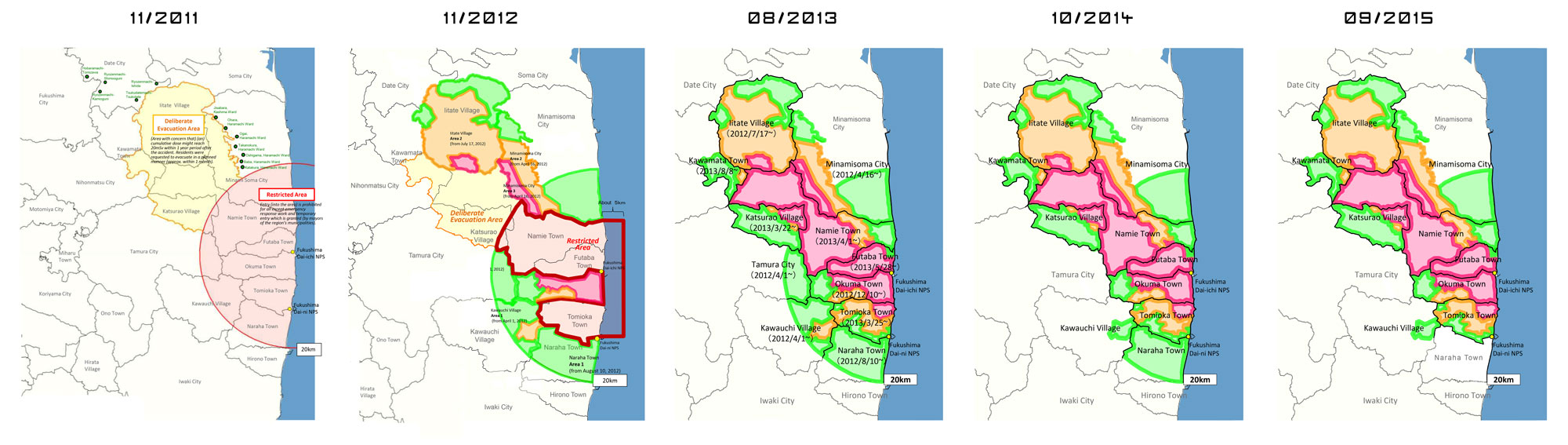

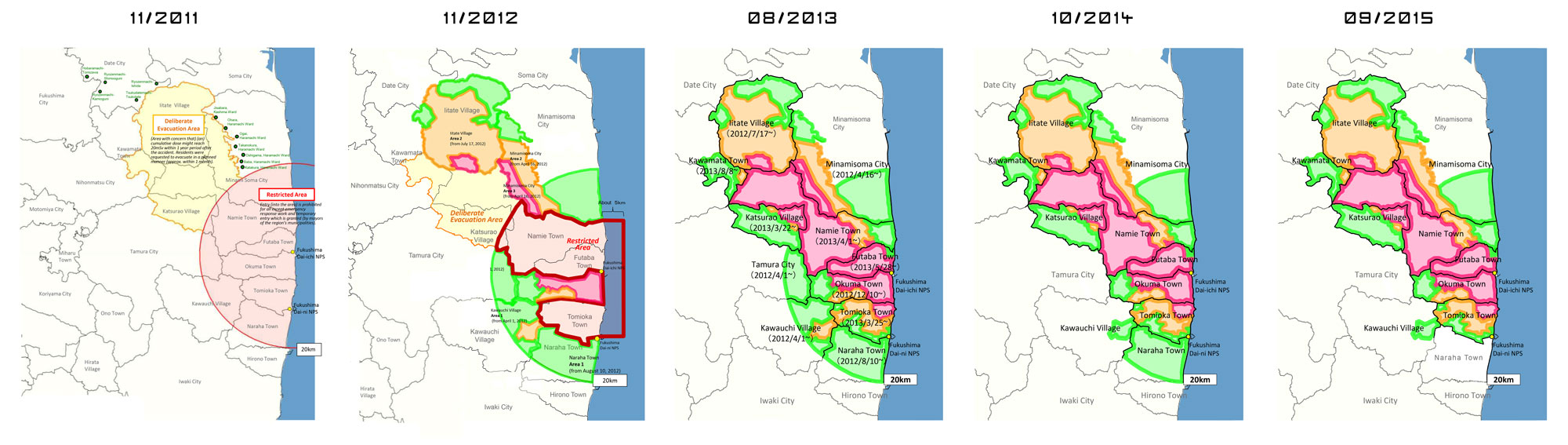

Immediately after the disaster at the Fukushima power station an area of 3 km, and later 20 km, was designated from which approximately 160 000 residents were forcibly evacuated. Chaos, and an inefficient system of monitoring radiation levels, resulted in many families being divided up or evacuated to places where the contamination was even greater. In the months and years that followed, as readings became more precise, the boundaries of the zone evolved. The zone was divided up according to the level of contamination and the likelihood that residents would return.

Four years after the accident more than 120 000 people are still not able to return to their homes, and many of them are still living in temporary accommodation specially built for them. As with Chernobyl, some residents defied the order to evacuate and returned to their homes shortly after the disaster. Some never left.

Changes in the boundaries of the zone between the years 2011 and 2015

It is not permitted to go to towns and cities located in the zone with the highest levels of contamination, marked in red, except with a special permit. Due to the high level of radiation (> 50 mSv/y), no repair or decontamination work is carried out there. According to the authorities’ forecasts the residents of those towns will not be able to return for a long time, if at all.

The orange zone is less contaminated but also uninhabitable, but because the level of radiation is less (20-50 mSv/y) clearing up and decontamination work is being done here. Residents are allowed to visit their homes but are still not allowed to live in them.

The zone with the lowest level of radiation (< 20 mSv/y) is the green zone, and decontamination work has been completed here. Now the clean-up is in its final stages, and soon the evacuation order is to be lifted.

DECONTAMINATION

When entering the zone, the first thing that one notices is the huge scale of decontamination work. Twenty thousand workers are painstakingly cleaning every piece of soil. They are removing the top, most contaminated layer of soil and putting it into sacks, to be taken to one of several thousand dump sites. The sacks are everywhere. They are becoming a permanent part of the Fukushima landscape.

Dump sites with sacks of contaminated soil are usually located on arable land. To save space they are stacked in layers, one on top of the other.

(海のそばに、汚染ゴミの山)

Millions of sacks. Aerial view.

The contamination work does not stop at removal of contaminated soil. Towns and villages are being cleaned as well, methodically, street by street and house by house. The walls and roofs of all the buildings are sprayed and scrubbed. The scale of the undertaking and the speed of work have to be admired. One can see that the workers are keen for the cleaning of the houses to be completed and the residents to return as soon as possible.

One of thousands of dump sites with sacks of radioactive soil

By hand, the roofs of all the buildings are cleaned one by one

What the workers, and in fact the government financing their work, want to achieve is not necessarily what the residents themselves want. The contaminated land is not reused, and doesn’t even leave the zone. It is only transported out of the town often not beyond the outskirts. This expensive operation is only the shifting of the problem from one place to another, just so long as it is outside of the town to which residents are soon to return.

It is still not clear where the contaminated waste will end up, especially as the residents protest against long-term dump sites being located near their homes. They are not willing to sell or lease their land for this purpose. They do not believe the government’s assurances that in 30 years from now the sacks containing the radioactive waste will be gone. They are worried that the radioactive waste will be there forever.

Residential building with a view over one of the waste dumps with radioactive soil

![]() http://www.labornetjp.org/news/2015/1008heiwa より転載

http://www.labornetjp.org/news/2015/1008heiwa より転載