古墳と関根家住宅という前橋市の「大室公園」。

関根家住宅のとなり側にはこの古墳のまわりにかつてあった

「古代集落」としての竪穴住居が復元建築されていた。

古墳は古代社会「集落」の中核痕跡。

多くの労力がその築造にはかかわり動員されていた。

その後の社会発展の中で「ムラ」という共同体になった社会一体性が

きっと存在していたに違いない。

支配者への奴隷的絶対服従ばかりとは考えられない部分があっただろう。

農業経済を基盤として関東「新開地」にあらたな人間社会が育っていった。

それまでの関東地域の状況というのは不明だけれど、

農業土木労働によって目的的に河川水を活用して

食料生産を計画的に行っていくという文化が初めて根付いていったのだろう。

吉野ヶ里遺跡で見られるように地域豪族と農業構成員集団による開発が

組織だって運営されていった。日本社会のコア部分。

支配層の痕跡は古墳などで残っているけれど、

かれらはかれらだけで生きられたわけではない。

その支配にしたがって、日々の生産活動に従事した民人が多数いた。

地域の教育委員会としてそういう人々の思いを追体験する住まいを

子どもたちの集団参加で復元している住居がみられた。

「建設作業参加者」ということで小学生多数の名が書かれていた。

その建設作業の様子も看板に写真入りで記録保存されている。

父兄のみなさんも名前があるので親子で参加されたのでしょう。

っていうか、写真を見る限り子どもたちのために

一生懸命作業に取り組んでいるお父さんたちの労働奉仕の様子が伝わる(笑)。

子どもたちから「お父さん頑張れ」という声援がこだまして

その声に夢中で応えていることがあきらか。微笑ましい。

竪穴というのはこの「地面の掘り下げ」からすべてが始まるけれど、

これは住まいの「安定した室内気温環境」を確保する根源的目的営為。

古代の人々が地域の気候のなかでどう安定的な暮らしの場を確保したか、

子どもたちは自身とお父さんたちの身を以て体験したでしょう。

地面を掘るスコップ状の道具とその作業はいわば人類の基本労働。

親子でいっしょに作業することで「世代を繋いでいく」という

住宅というものの本質を噛みしめられたのではないだろうか。

出来上がった住居は凜としていて、

子どもたちの「作った誇り」のようなものが自然と感じられた。

「おお、すごい。よくやったなぁ」

はるかなご先祖さまたちの家づくりの苦労を体験できる機会って

なかなか得がたい体験だろうと思う。じんわり感動。

English version⬇

Children's Participation in Making a Pit Dwelling in Maebashi Omuro Park

Restoration of the pit of our ancestors. Securing a "stable indoor environment" to sustain life. Children facing the basic "use" of humankind. Children's participation in the construction of a pit dwelling.

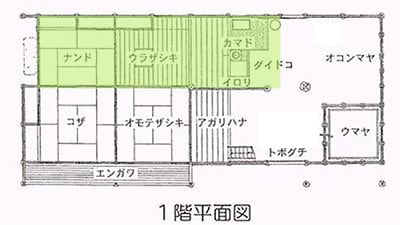

Omuro Park" in Maebashi City is a place of ancient burial mounds and the Sekine family residence.

The Sekine family residence is located next to an "ancient village" that once existed around the burial mound.

The burial mound is a core trace of an ancient "settlement".

Kofun tumuli are the core traces of "settlements" in ancient society.

A lot of labor was involved in their construction.

In the subsequent development of society, there must have existed a social unity that became a community called "mura".

must have existed.

There must have been more than just slavish obedience to the rulers.

A new human society grew up in the Kanto region based on the agricultural economy.

Although the situation in the Kanto region up to that time is unknown

The culture of planned food production was based on the purposeful use of river water through agricultural and civil engineering labor.

The culture of systematic food production by purposefully utilizing river water through agricultural engineering labor must have taken root for the first time.

As can be seen at the Yoshinogari site, development was organized and managed by local powerful families and agricultural groups.

and agricultural groups, as seen at the Yoshinogari site. This is the core of Japanese society.

Traces of the ruling class can be found in ancient tombs, but they did not live on their own.

they were not able to live on their own.

There were many people who were engaged in daily productive activities in accordance with the ruling class.

As a local educational committee, we are restoring a house to relive the thoughts and feelings of these people with the collective participation of children.

The local board of education is restoring the houses with the collective participation of children.

The names of many "first grade elementary school students" were written as "participants in the construction work.

The construction work was also recorded and preserved on the signboard with photographs.

The names of the parents are also on the sign, so it is likely that both parents and children participated in the construction.

Or rather, the photos show that they were there for the children.

The fathers' labor service is conveyed as they work hard (laughs).

The children were cheering "Go, Dad!

It was obvious that the fathers were enthusiastically responding to the children's cheers. It was very funny.

In a pit, everything begins with this "digging of the ground.

This is a fundamental activity to ensure a "stable indoor temperature environment" for the house.

We can learn how ancient people secured a stable place to live in the local climate.

The children will have experienced firsthand how ancient people secured a stable living environment in the local climate, both themselves and their fathers.

The shovel-like tools used to dig the ground and the work involved are the basic labor of mankind.

By working together, parents and children were able to understand the essence of "passing down the generations.

I am sure that by working together, parents and children were able to understand the essence of housing, which is to "pass it on from generation to generation.

The finished house was interesting and interesting.

The children's pride in their work was evident.

The children were naturally proud of their work, saying, "Wow, that's great. You did a great job.

It must be a rare opportunity to experience the hard work of our distant ancestors in building their homes.

I think it must be a very rare experience to have the chance to experience the hard work of our ancestors in building their houses. I was deeply moved.