昨日、日本の囲炉裏と西洋の暖炉について書いていて、家族からの率直な感想チェックで気付かされたこと。「坐る」文化と椅子の文化による違いという視点。言われてみて、あまりにも腑に落ちた次第。

しかし日本文化の特徴である囲炉裏は「食遊」の空間でもあったことが、西洋社会の暖炉文化とは大きく相違していったということか。暖炉では、たとえば肉を串刺しして輻射熱調理して食べるという文化は優勢ではない。一方、日本の囲炉裏では灰ガラをほどよく積層させそこに串を立てて調理する文化が根付いた。日本料理では肉類はあくまでも「鍋」のうまみとして食することが主流で、魚こそがこうした串刺し料理にふさわしく、海に囲まれ多様の河川に恵まれた風土によって支配的食文化になっていった。

暖炉には食文化涵養の痕跡は乏しいのではないか。さらに中国文化圏では囲炉裏はどうも多数派の生活文化にはなっていないように思う。むしろ暖炉の方に寄っていると思える。また朝鮮半島や北東アジアで一般的な床暖房のオンドルでの調理文化もあまり聞かない。このあたりはもうちょっと探索してみたい。

ちなみに暖炉のWikiページには以下のような記述。「暖炉は特に西洋では部屋の格式や、席次を決める上での重要な調度品であり、暖炉周りのマントルピースなどの装飾には力が注がれる 」とある。このあたりは、日本文化でも同様で,きのう書いたように席次による格式が顕著に存在した。

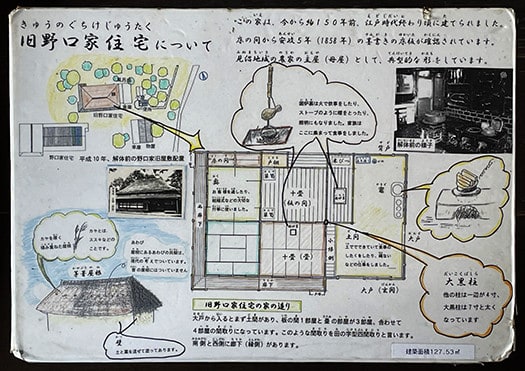

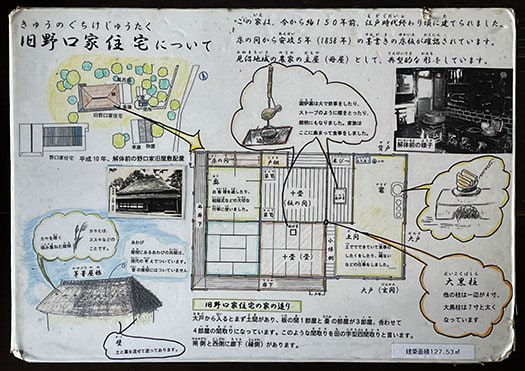

で、この「席次序列」の考え方・思考法は日本家屋全体にわたって展開していくことになる。いちばん上の写真はこの神仏習合庫裡のいちばんの格式空間、床の間付き座敷。

今日でもこうした空間に出会うと日本人は、席を譲り合うという独特の社会儀礼がある。

「○○さんは、ぜひこちらに」

「いえいえ、わたしなぞ末席を汚させていただきます、あなたこそこちらへ」

みたいな予定調和的言葉掛け、やり取りが日本人DNAには仕込まれている。「床柱が似合う」というような人物評価の言語表現も存在している。こういう「空気感」感受性こそが日本人「らしさ」の究極かも。

この席次序列の考え方が日本建築には色濃く伝承されていった。

わたしは北海道生まれであり、こういう席次序列文化による間取り構成住宅からは最初期に離脱した住文化社会に属している。しかし、日本人としてのDNAはまだこういう空間に反応したくなる部分がある。畳がお尻に微妙な繊維質感を伝えて、その快感にウットリするような(笑)。

椅子やソファでの暮らしで寒さ暑さから解放された高断熱高気密ライフスタイルに圧倒的に満たされながら、たまに外食するなら、炭火の囲炉裏端みたいな店内インテリアの空間で、できれば魚の串焼きに癒されたいという内奥からの欲求もあるのだ。ニッポン的ごちゃ混ぜ生活文化か(笑)。

English version⬇

Japanese "sitting" cultural prestigious expression: Hikawa Shrine and Anraku-ji Temple Kori-5

The family's straightforward impression became clear to me. The Japanese architectural culture of sitting, a lifestyle culture derived from Irori (hearth), deeply engraved in our DNA. The Irori-derived lifestyle culture deeply imprinted in our DNA.

Yesterday, when I wrote about Japanese hearths and Western fireplaces, I was reminded by an honest feedback check from a family member. The difference between the culture of sitting and the culture of chairs. When I was told this, it became all too clear to me.

The hearth, a characteristic of Japanese culture, was also a space for "eating and playing," which was very different from the fireplace culture of Western society. In the fireplace, for example, the culture of skewering meat and eating it cooked by radiant heat is not predominant. On the other hand, in Japan, the culture of cooking meat on skewers in a hearth with a good layer of ash and ash residue has taken root. In Japanese cuisine, meat is usually consumed as a "nabe" (pot), and fish is the most suitable for this kind of skewered food.

The fireplace may be a poor evidence of the cultivation of food culture. Furthermore, in the Chinese cultural sphere, the hearth does not seem to have become a dominant part of the lifestyle culture. Rather, it seems to be more in the direction of fireplaces. Also, I have not heard much about the cooking culture using ondol, a floor heating system commonly used in the Korean Peninsula and Northeast Asia. I would like to explore this area a little more.

Incidentally, the Wiki page on fireplaces has the following description. The fireplace is an important furnishing in determining the prestige of a room, especially in the West, and a lot of effort is put into decorating the mantelpiece and other parts around the fireplace. As I wrote yesterday, there was a pronounced hierarchy of seating in the Japanese culture as well.

This "seating order" concept and way of thinking developed throughout the Japanese house. The photo above is the most prestigious space in the kori, which is a combination of the Shinto and Buddhist temples, with a tokonoma (alcove).

Even today, when encountering such a space, Japanese people have a unique social ritual of giving up their seats to each other.

"Please come this way, Mr. XX.

No, no, no, I'm sorry to make a mess of your seat, you go this way.

Such scheduled exchanges of words and phrases are ingrained in the DNA of the Japanese people. There is also a verbal expression of character evaluation, such as, "You look good in the tokonobashira. This kind of "airiness" and sensitivity may be the ultimate in Japanese "character.

This concept of the pecking order has been passed down strongly in Japanese architecture.

I was born in Hokkaido, and belong to a housing culture society that has moved away from this type of floor plan structure in the early stages of its history. However, as a Japanese, there is still a part of my DNA that wants to respond to this kind of space. The tatami conveys a subtle fiber texture to the buttocks, and the pleasant sensation makes me swoon (laughs).

While overwhelmingly satisfied with the highly insulated and airtight lifestyle of living on chairs and sofas, free from cold and heat, there is also a desire from deep within to eat out occasionally, preferably in a space with a restaurant interior like a charcoal sunken hearth edge, and to be soothed by grilled fish skewers. It is the Nippon way of life and culture, a mixture of the two.