まことに力強いお姿の鹿島神宮祭神・武甕槌大神であります。鹿島神宮奥の院のさらに森の中にある。暴れ狂う地震発生源・大ナマズに足を載せ、押さえつけている神々しく凜とした表情。わかりやすい(笑)。

きのう触れたようにこの関東の武神は出雲に対し「国譲り」を武力を持って迫ったと言われる。ヤマト王権成立のときにそういう活躍をしたことから、王権にとってまだ十分な支配体制が整っていなかった関東を鎮守していく役割を担っていたのかと思える。建国時期の神話世界のことなので、このふたつの事柄の前後関係は不明だけれど、関連はあるだろう。このことがなんらかの事実に導かれた説話なのか検証しようはないけれど、さりとて根も葉もないこととも言い切れない。

そういったあわい神話の世界でいかにも人にわかりやすく神威を示すのがこの地震を抑え込むポーズ。

関東は記録に残る江戸期にも大正期にも、大震災に見舞われ続けている地域。地震・雷・火事・オヤジという「荒ぶる大地」の鎮守として男性的なイメージがふさわしいと歴世、語り継がれてきたのだろう。

地震多発地域というのはたぶん縄文期以来、この地域に暮らしてきた人びとの実感であったことだろう。そうした人知を越えた自然現象に対して、素朴な「祈る」こころ、信仰心は存在し続けていただろう。

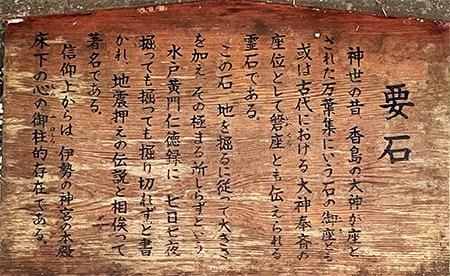

この鹿島神宮にも相関する香取神宮にも「要石」が重要な存在として祀られている。さらに東国三社のもうひとつとされる息栖神社にも「力石」が納められている。地震が頻発し、利根川などの暴れ川が氾濫を繰り返す不安定な地域では、こうしたパワーへの帰依、信仰心が人心にふさわしかったのではないか。相対的には自然のパワーにやわらかさの感じられる畿内地域とは宗教心において下地に違いがあるように思う。

こういったパワー信仰がベースにあってその後の開発領主層の「武士化」、力こそがすべてという軍事政権を生み出していくことになったというのが歴史の本質。

ヤマト王権にとって伊勢神宮は、現世権力の正統性を担保する宗教的存在として機能してきたのだろうけれど、関東では鹿島と香取というように信仰心は分散されてきた。このことはその後の日本史の展開にとってカギを握ってきたことなのかも知れない。畿内では伊勢神宮という宗教が担保することによって万世一系という権力が安定がしたけれど、関東・東国で成立した武権においては、鎌倉幕府では源氏の血筋というそれ自体は王権側の制度機能によってコントロールされ、江戸幕府に於いてはその創設者自身が神君として東照大権現という別の権威体系を独自に作った。

鹿島や香取は、その随伴的な位置に留められたという歴史の流れがあるのだろう。案外、鹿島に一元化されていたら、微妙にその後の日本史に影響しを与えたのではないだろうかと妄想。

English version⬇

Kashima Jingu Shrine, the Kanto region's earthquake-prone Shinto shrine

Since the Jomon period, when settlement began, Kanto has been a watery region similar to the Seto Inland Sea and an earthquake-prone area. Did the people nurture a disposition that favored masculine authority? ...

This is Takemikazuchi, the deity of Kashima Jingu Shrine, with a truly powerful appearance. It is located further into the forest in the inner sanctuary of Kashima Jingu Shrine. The godly and interesting expression on his face as he places his foot on the rampaging earthquake generator, the giant catfish, and holds it down. It is easy to understand (laugh).

As I mentioned yesterday, it is said that this Kanto no Mikoto (warrior god) was the one who used force to force Izumo to hand over the land to the Yamato kingdom. Since he played such an active role at the time of the establishment of the Yamato kingdom, it seems likely that he played a role in protecting the Kanto region, which was not yet fully under the control of the Yamato kingdom. Since this is the mythical world of the time of the founding of the Yamato Kingdom, the relationship between these two events is not clear, but there must be a connection. Although there is no way to verify whether this is based on fact or not, it cannot be said that it is a myth.

In such a world of myths, it is the pose of suppressing earthquakes that is so easily understood by people.

The Kanto region has been hit by earthquakes since the Edo period (1603-1868) and Taisho period (1912-1926). The masculine image of the god has been passed down from generation to generation as an appropriate deity to protect the "rough and tumble land" of earthquakes, lightning, fire, and father figures.

People who have lived in this region since the Jomon period probably felt that it was an earthquake-prone area. In response to such natural phenomena that transcend human knowledge, the simple spirit of "prayer" and religious beliefs must have continued to exist.

The Katori Jingu Shrine, which is related to the Kashima Jingu Shrine, also enshrines a "keystone" as a significant presence. Furthermore, the "Yokuishi" is also enshrined at the Ikisu Shrine, another of the three shrines in the eastern part of Japan. In an unstable region where earthquakes are frequent and rivers such as the Tone River repeatedly overflow, devotion and faith in such power may have been appropriate to the human mind. Relatively speaking, there seems to be a difference in the grounding of religious beliefs between the Kinai region, where the power of nature seems to have a softer touch, and the Kinai region, where the power of nature seems to have a softer touch.

The essence of history is that this belief in the power of nature was the basis for the subsequent "samurai-ization" of the development lords and the creation of a military regime in which power was everything.

For the Yamato kingdom, the Ise Jingu shrine may have functioned as a religious presence to ensure the legitimacy of its temporal power, but in the Kanto region, religious beliefs were dispersed, as in the case of Kashima and Katori. This may have been a key factor in the subsequent development of Japanese history. In the Kinai region, the religious institution of Ise Jingu Shrine ensured the stability of power in the form of a lineage of ten thousand generations, while in the Kanto and Tōgoku regions, the Kamakura shogunate was mentally controlled by the institutional function of the royal authority, which itself was the lineage of the Minamoto clan, and in the Edo shogunate, the founder of the Edo shogunate himself was the sovereign deity of the Tōshō-dai Gongen. In the Edo shogunate, the founder of the shogunate himself created a separate system of authority called Tōshō-tai Gongen as a deity.

Kashima and Katori were kept in the same position as their followers. If they had been centralized in Kashima, it may have had a subtle influence on the subsequent history of Japan.