現代の建築は日本の建築文化にとってどんな存在なのだろうか。ふと考えることがある。日本の建築・空間への感受性の文化伝承は、この竹林寺には豊富に積層している。

写真は竹林寺本坊と名勝庭園の様子。庭と建物の関係は日本ではこのような美的昇華が図られていって、日本文化の底流に沈殿している。このような様子を見ると建築構造本体は、切り取られた風景としての自然のなかで「息をしている」存在のように感じられる。

人間が造作する建物は外皮であって自然と向き合うとき五感と一体化している感覚がある。対して庭もまた、人為的に空間構成された自然であり、建物とは違う成り立ちではあるけれど、人間の美的選択眼に即して展開構成しているもの。

やはり「家庭」というような日本人の言い方は、いかにも日本文化的な表現なのだと思う。

こんなふうに先人たちは仏教寺院などに託して、それぞれの時代の美的感覚をピンナップして、連綿とわたしたちに建築文化を伝えてきてくれているのだと思う。その舞台装置として寺院という存在はそれこそ、この世とあの世の臨界点としてあり続けたのだろう。

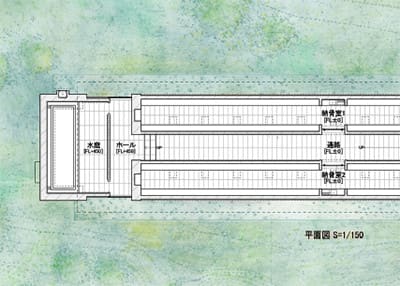

そういう文化背景のなかで現代の建築家・堀部安嗣さんは、先日まで観た「竹林寺納骨堂」を作り上げていった。そのときの端正な創造姿勢がなんとなくわかるような気がする。

玄関にはこんなふうな豪華な花が生けられてもいた。日本各地域のこうした名刹寺院などで日本的感受性を沈殿させ続けてきたのがこの国の文化風土なのでしょう。

ひるがえって、北海道はこういう「自然とのウチソト空間連続性」のようなことに難しさがある。

こんなふうな庭との空間開放体験を一般化しにくい。初期の北海道建築でそれでもこうした「一体化」を志向した建築の流れもあったけれど、半年間に近い寒冷気候とそれによる建物の障害要因によってこうした建築と同じようなライフスタイルはやはり取れなかった。この建物を撮影したのは1月の初旬なのだ。北海道では雪に庭が閉ざされ、また寒気が居住空間を襲撃する。

庭との対話も3重ガラスなどによる厳重な空間保護が前提化する。場合によっては屋根からの落雪堆積が眺望全体を潰滅させる。

しかし、そういう自然環境の中でも、わたしたちは日本人なのだ。創意工夫しながら「拡張する花鳥風月」を暮らしの中で楽しみたいと念願している。困難はむしろ発展の最大の資産だと無理矢理にでも、考えたい。

English version⬇

Japanese Architecture, Spatial Culture, and Hokkaido: Chikurinji Temple Visit-7

Japanese architectural design was made possible by a dialogue with the gentle climate. The northern part of Japan wants to share its essence and challenge a new Japanese design.

What kind of presence does contemporary architecture have in Japanese architectural culture? I sometimes think about this. The cultural legacy of Japanese sensitivity to architecture and space is richly layered in this Chikurinji temple.

The photo shows the main temple of Chikurin-ji and its famous garden. The relationship between garden and building has been aesthetically sublimated in Japan in this way, and has been precipitated in the undercurrent of Japanese culture. In this way, the architectural structure itself seems to "breathe" in the nature as a cutout landscape.

The human-made building is an outer skin, and when confronted with nature, there is a sense of being united with the five senses. A garden, on the other hand, is also nature artificially created in space, and although it has a different origin from a building, it is developed and structured in line with the human eye for aesthetic selection.

I believe that the Japanese way of saying "home" is a very Japanese cultural expression.

In this way, our predecessors have passed on their architectural culture to us through Buddhist temples, pinning down the aesthetic senses of their respective eras. As a stage set for this, the existence of temples has been a critical point between this world and the next.

It was against this cultural background that the contemporary architect Yasutsugu Horibe created the "Chikurinji Ossuary," which I saw the other day. I think I can somehow understand his neat creative attitude at that time.

The entrance was decorated with such gorgeous flowers. The cultural climate of this country has continued to precipitate Japanese sensibilities at such famous temples and other places in various regions of Japan.

Hokkaido, on the other hand, has difficulty with this kind of "uchisoto spatial continuity with nature.

It is difficult to generalize the experience of opening up space with a garden in this way. Although there was a trend in early Hokkaido architecture toward such "integration," the cold weather of nearly half a year and the resulting building obstacles made it impossible to achieve the same lifestyle as this type of architecture. It was early January when I photographed this building. In Hokkaido, the garden is closed by snow and the cold air attacks the living space.

The dialogue with the garden is also premised on the strict protection of the space with triple glazing and other measures. In some cases, the accumulation of snow falling from roofs destroys the entire view.

However, even in such a natural environment, we are Japanese. We wish to enjoy the "expanding beauty of flowers, birds, wind, and the moon" in our daily lives with our ingenuity and ingenuity. We would like to think, even if forcibly, that difficulties are the greatest asset for development.