さて日本列島での旧石器時代の社会実相を国立歴史民俗博物館展示で考えてきた。

わたし的にはコペルニクス的学習機会であり刺激的でした。

石器を基本ツールとしながら現代のわれわれの文化に繋がってきた

マザーでありその「進化過程」を掘り下げるという視点。

現代の考古の知見は炭素年代法というモノサシを活用して

このような社会実相に迫ってきていることが学習できてワクワクさせられた。

展示パネルの興味深い部分に沿って考えをまとめながら連載してみた。

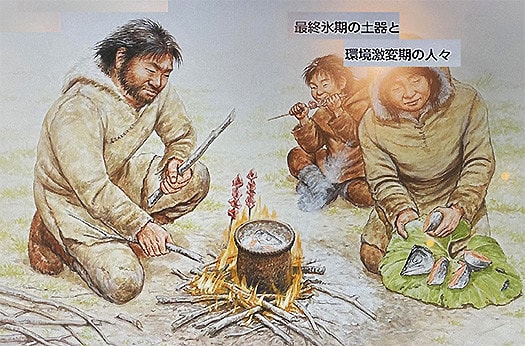

で、この22,000年以上と言われる旧石器段階から縄文への移行について。

必ずしも展示にそのような結論があったわけではないけれど、

わたし的に非常に印象深かったのが「食の革命的変化」。

縄文を特徴付けるもっとも核心は土器料理の普遍的採用だということ。

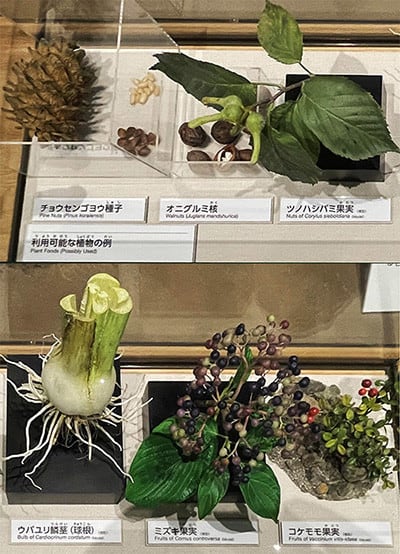

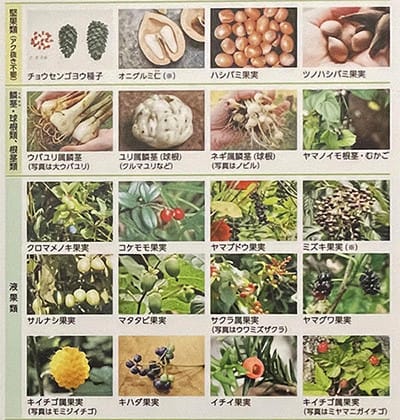

一方で旧石器のひとびとの食のスタイル展示の中に

「石蒸し料理」の紹介があって実にシンボリックだと感じたのです。

肉や魚などはそのまま火に炙って食べるのが一般的だろうけれど、

栄養バランスから考えて必須の写真のような植物性食品調理には適さない。

焼くだけでは炭化が進むだけでうま味を味わうことができない。

平成3年に見つかった浅間山麓の長野県・下弥堂遺跡での発掘写真。

見つかったのは川原石をぎっしりと敷き詰めた穴。「石蒸し料理」キッチン。

調理手順は以下のようだとされている。

1 握りこぶし大の石を穴に入れる。

2 石がカンカンに熱くなるまでその上で火を焚く。

3 ホウの葉などの木の葉で包んだ食材を石の上に並べる。

4 その上に土をかぶせて1時間ほど蒸し焼きにする。

5 食材を土の中から取りだし葉を開いて食べる。

こういう調理法は現代のパプアニューギニアなどの民俗例でも見られるという。

実際にわたしも石蒸し料理は食べたことがあるけれど、食材に良く火が通って

非常に香ばしくジューシーな食感を楽しめる。

ポイントは食材をしっかり葉で包むこと。こういう料理法は

現代にも蒸し焼き料理として連綿とあり続けている。マザーな食文化。

人類の進化の中で、食文化というのはかなり決定的なファクター。

そして料理法というのは食材の栄養とうま味を極限まで追究するもの。

肉も魚も最重要な食材で焼くだけでもおいしいけれど、

他の植物性食材にうま味を染み込ませて同時に食する「進化」が

当然に追究されていったに違いないと思うのです。

そうすると上から2番目の「縄文土器」での「鍋料理」は革命的に合理的。

石蒸しはおいしいのは格別だけれど調理に手間がかかる。

対して土器だと簡易でいわゆる鍋料理のルーツとして日本食文化で基底的。

多様な食材を渾然一体として受け入れる柔軟性も高い。

日本人の精神的原型・ルーツとしても縄文土器での食生活は

大きな影響力を持ったのではないか。

獲得が陸生動物と比較して容易で「平和的入手」可能な魚をベースにして、

そのうま味を余すところなく引き出すのは、精神性も含めて日本人らしい。

どうも時代の変化は、この食の革命が静かな起因だったのではないか。

日本列島での時代変容にはこういう平和的な移行がふさわしかったのだとも

思われてならないのであります。さてどうかなぁ?

次回以降は、次の世、縄文探究に進みたいと思います。

English version⬇

Stone Steaming ➡ Jomon Pottery "Revolution of Food" 37,000 Years History of the Japanese Islands - 10

From cooking only by baking to "boiling" food culture. There may have been a "steaming" cooking culture at the halfway point. Peaceful transition of the times. ...

I have been thinking about the social reality of the Paleolithic in the Japanese archipelago at the National Museum of Japanese History exhibition.

For me, it was a stimulating Copernican learning experience.

Stone tools are the basic tools that have led to our modern culture.

The perspective of delving into the "evolutionary process" of the mother culture, which has led to our present culture using stone tools as basic tools.

Modern archaeological knowledge is based on carbon dating, which is a method that allows us to understand the realities of society.

It was exciting to learn that modern archaeological findings are approaching such social realities through the use of carbon dating.

I have tried to write a series of articles summarizing my thoughts along with the interesting parts of the exhibition panels.

I was also interested in the transition from the Paleolithic to the Jomon period, which is said to be 22,000 years ago.

I was very impressed with the "transition from the 22,000 year old Paleolithic to the Jomon period," although I did not necessarily draw that conclusion from the exhibit.

I was very impressed by the "revolutionary change in food".

The most central characteristic of the Jomon is the universal adoption of earthenware cuisine.

On the other hand, in the Paleolithic people's food style exhibit

I thought it was very symbolic.

It is common to eat meat and fish by roasting them over a fire.

However, from a nutritional balance point of view, it is not appropriate for cooking essential plant foods such as those in the photo.

Grilling alone only leads to carbonization and does not allow you to taste the umami flavor.

Excavation photo from the Shimoyado Site, Nagano Prefecture, at the foot of Mount Asama, discovered in 1991.

What was found was a pit tightly packed with riverbed stones. A "stone steaming" kitchen.

The cooking procedure is said to be as follows.

1. Place a stone the size of a fist in the hole.

2. Build a fire over the stones until they are very hot.

3 Place the food, wrapped in leaves such as borax leaves, on the stone.

4 Cover the top with soil and let it steam for about an hour.

5 The food is removed from the earth, the leaves are opened, and the food is eaten.

This method of cooking is said to be found in modern folklore in Papua New Guinea and elsewhere.

I have actually eaten stone steamed food before, and it was very fragrant and juicy.

The key point is to wrap the food tightly in the leaves.

The key is to wrap the food tightly in the leaves. This kind of cooking method is still used today.

still exist today as steamed dishes. Mother food culture.

Food culture is a decisive factor in human evolution.

Cooking methods are based on the pursuit of the nutrition and umami of the ingredients to the utmost limit.

Meat and fish are the most important ingredients, and they are delicious just by grilling them.

But the "evolution" of infusing umami into other plant-based ingredients and eating them at the same time

I believe that "evolution" must have been pursued naturally.

In that case, "nabe cooking" with Jomon earthenware, the second item from the top, is revolutionary and rational.

Stone steaming is exceptionally tasty, but it takes a lot of time and effort to cook.

Earthenware, on the other hand, is simple and is fundamental to Japanese food culture as the root of so-called "nabe" cooking.

It is also flexible enough to accept a variety of ingredients as a whole.

The Jomon earthenware diet must have had a great influence on the spiritual prototype and roots of the Japanese people.

The Jomon earthenware diet may have had a great influence on the spiritual prototype and roots of the Japanese people.

The Jomon diet was based on fish, which was easier to acquire than land animals and could be obtained "peacefully".

It is typical of the Japanese, including their spirituality, to draw out the full flavor of fish.

Apparently, the change of the times was quietly caused by this food revolution.

I can't help but think that this kind of peaceful transition was appropriate for the transformation of the times in the Japanese archipelago.

I can't help but think that this kind of peaceful transition was appropriate for the transformation of the times in the Japanese archipelago. What do you think?

From next time onward, I would like to move on to the next generation, the Jomon exploration.