八剣山というのは札幌市南区にある独特の姿の山。

小さいときから「ゴジラの背中・・・」という刷り込み。

札幌市南区は札幌の中でもいちばん自然環境の保全された地域で

他区のように宅地開発されていない。

いまのような行動抑制の環境下ではこうした手近な自然はありがたい。

日曜日に夫婦でちょっとした「遠出」ということで行ってみた。

「八剣山って、岩の露出した峰が8つだよね?」

「う〜ん、そう言われてるけど・・・」

「え〜っと、1、2、3・・・」

ということで、この山を見ていると多くの人がなぞかけされる(笑)。

だいたいこういう場合、人間としては向かって左側から数える。

で、6くらいまではわかるのだけれど、その先の右端が不明になる。

いっそ峰に数字を刻印してほしい、という自然環境破壊の衝動にもかられる(笑)。

以下、紹介文は「北海道地質百選」から要旨抜粋。

〜八剣山は、札幌から南西に15kmほど離れた標高498mの山。

札幌から定山渓に向かう国道230号線の右手にみえる

「恐竜の背骨」のような稜線として知られ背骨のように連なる多くの岩峰から、

八剣山と呼ばれています。別名で観音岩山とも呼ばれています。

八剣山は新第三紀中新世の砥山層を貫く貫入岩体(複輝石安山岩)であると

推定され南口登山口周辺では垂直方向に発達した柱状節理が観察できます。

山頂部には鋭くとがった岩峰、北西-南東方向の岩脈(石英角閃石輝石デイサイト)が

露出しており水平方向に発達した柱状節理が特徴的。

安山岩の貫入岩体は6.7Ma(K-Ar法)山頂部のデイサイトは4Ma(K-Ar法)の

年代値が報告されています。【執筆者:鬼頭伸治】〜

で、最近はふもとにワイナリー農園とレストランがあって、

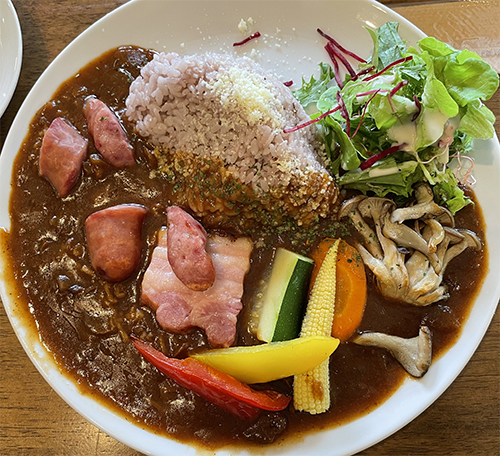

お昼時だったので、ごらんのような食事をいただきました。

ちょっと色合いは濃い目で「辛いか、塩っぱいか」と不安だったのですが

食べてみると案外さらっとした味わいで美味しかった。

なにやら「八剣山なんとか」という名前だったような・・・。

どうもこういう大自然のなかにいると細かいことに注意は向かなくなる。

北海道人が、よく言えば「おおらか」悪く言えば「大ざっぱ」なのには

圧倒的な自然の豊かさが人間を包み込む感覚が与っている。

まぁ6つでも8つでもどっちでも大差はない。いいじゃん。

そもそも八という数字には「たくさん」という意味合いがあって

名付けにはそういう意味が込められているようにも思います。

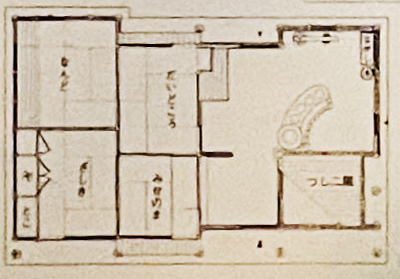

ということで恐縮ですが、みなさん目をこらして峰の数、勘定してみてください。

English version⬇

A Season of Dripping Greenery, Counting the Peaks of Hakkenzan...

In a period of behavioral restraint, we are embraced by the local nature. Come to think of it, I haven't been able to count the peaks of Hakkenzan since I was a child. Hmmm... ...

Hakkenzan is a unique looking mountain located in Minami Ward, Sapporo City.

Since I was a child, I have been imprinted with the image of "Godzilla's back...".

Minami Ward is the most natural environment-preserved area in Sapporo.

The area has not been developed into residential areas like other wards.

In today's action-restrained environment, such close proximity to nature is a blessing.

On Sunday, a couple of us went for a short "outing.

They said, "Hakkenzan has eight peaks with exposed rocks, right?"

"Ummm, that's what they say, but..."

"Well, one, two, three..."

So many people are riddled with riddles when they see this mountain (laughs).

(Laughs) In such cases, people usually count from the left side of the mountain.

So, we can figure out up to about 6, but after that, the right end of the mountain is unknown.

I am tempted to destroy the natural environment by having the numbers engraved on the peaks (laugh).

The following is an excerpt from the introduction.

So, recently there was a winery farm and restaurant at the foot of the mountain.

It was lunchtime, so we had a meal like the one you see below.

I was a little worried that it might be too spicy or salty, but when I tried it

But when I tried it, I found it to be surprisingly light and tasty.

I think the name of the dish was something like "Hakkenzan" or something like that.

I don't pay attention to details when I am in such a great nature.

Hokkaido people are at best "generous" and at worst "messy.

The overwhelming abundance of nature that surrounds us gives us a sense of being surrounded by nature.

Well, there is no difference whether there are six or eight. It's fine.

In the first place, the number eight has the meaning of "a lot.

I think that the naming of the house has such a meaning.

So, I am sorry to say this, but please try to count the number of peaks with your eyes.