Seventy-one years ago, on a bright cloudless morning, death fell from the sky and the world was changed. A flash of light and a wall of fire destroyed a city and demonstrated that mankind possessed the means to destroy itself.

Why do we come to this place, to Hiroshima? We come to ponder a terrible force unleashed in a not-so-distant past. We come to mourn the dead, including over 100,000 Japanese men, women and children, thousands of Koreans, a dozen Americans held prisoner.

Their souls speak to us. They ask us to look inward, to take stock of who we are and what we might become.

It is not the fact of war that sets Hiroshima apart. Artifacts tell us that violent conflict appeared with the very first man. Our early ancestors having learned to make blades from flint and spears from wood used these tools not just for hunting but against their own kind. On every continent, the history of civilization is filled with war, whether driven by scarcity of grain or hunger for gold, compelled by nationalist fervor or religious zeal. Empires have risen and fallen. Peoples have been subjugated and liberated. And at each juncture, innocents have suffered, a countless toll, their names forgotten by time.

The world war that reached its brutal end in Hiroshima and Nagasaki was fought among the wealthiest and most powerful of nations. Their civilizations had given the world great cities and magnificent art. Their thinkers had advanced ideas of justice and harmony and truth. And yet the war grew out of the same base instinct for domination or conquest that had caused conflicts among the simplest tribes, an old pattern amplified by new capabilities and without new constraints.

In the span of a few years, some 60 million people would die. Men, women, children, no different than us. Shot, beaten, marched, bombed, jailed, starved, gassed to death. There are many sites around the world that chronicle this war, memorials that tell stories of courage and heroism, graves and empty camps that echo of unspeakable depravity.

Yet in the image of a mushroom cloud that rose into these skies, we are most starkly reminded of humanity’s core contradiction. How the very spark that marks us as a species, our thoughts, our imagination, our language, our toolmaking, our ability to set ourselves apart from nature and bend it to our will — those very things also give us the capacity for unmatched destruction.

How often does material advancement or social innovation blind us to this truth? How easily we learn to justify violence in the name of some higher cause.

Every great religion promises a pathway to love and peace and righteousness, and yet no religion has been spared from believers who have claimed their faith as a license to kill.

Nations arise telling a story that binds people together in sacrifice and cooperation, allowing for remarkable feats. But those same stories have so often been used to oppress and dehumanize those who are different.

Science allows us to communicate across the seas and fly above the clouds, to cure disease and understand the cosmos, but those same discoveries can be turned into ever more efficient killing machines.

The wars of the modern age teach us this truth. Hiroshima teaches this truth. Technological progress without an equivalent progress in human institutions can doom us. The scientific revolution that led to the splitting of an atom requires a moral revolution as well.

That is why we come to this place. We stand here in the middle of this city and force ourselves to imagine the moment the bomb fell. We force ourselves to feel the dread of children confused by what they see. We listen to a silent cry. We remember all the innocents killed across the arc of that terrible war and the wars that came before and the wars that would follow.

Mere words cannot give voice to such suffering. But we have a shared responsibility to look directly into the eye of history and ask what we must do differently to curb such suffering again.

Some day, the voices of the hibakusha will no longer be with us to bear witness. But the memory of the morning of Aug. 6, 1945, must never fade. That memory allows us to fight complacency. It fuels our moral imagination. It allows us to change.

And since that fateful day, we have made choices that give us hope. The United States and Japan have forged not only an alliance but a friendship that has won far more for our people than we could ever claim through war. The nations of Europe built a union that replaced battlefields with bonds of commerce and democracy. Oppressed people and nations won liberation. An international community established institutions and treaties that work to avoid war and aspire to restrict and roll back and ultimately eliminate the existence of nuclear weapons.

Still, every act of aggression between nations, every act of terror and corruption and cruelty and oppression that we see around the world shows our work is never done. We may not be able to eliminate man’s capacity to do evil, so nations and the alliances that we form must possess the means to defend ourselves. But among those nations like my own that hold nuclear stockpiles, we must have the courage to escape the logic of fear and pursue a world without them.

We may not realize this goal in my lifetime, but persistent effort can roll back the possibility of catastrophe. We can chart a course that leads to the destruction of these stockpiles. We can stop the spread to new nations and secure deadly materials from fanatics.

And yet that is not enough. For we see around the world today how even the crudest rifles and barrel bombs can serve up violence on a terrible scale. We must change our mind-set about war itself. To prevent conflict through diplomacy and strive to end conflicts after they’ve begun. To see our growing interdependence as a cause for peaceful cooperation and not violent competition. To define our nations not by our capacity to destroy but by what we build. And perhaps, above all, we must reimagine our connection to one another as members of one human race.

For this, too, is what makes our species unique. We’re not bound by genetic code to repeat the mistakes of the past. We can learn. We can choose. We can tell our children a different story, one that describes a common humanity, one that makes war less likely and cruelty less easily accepted.

We see these stories in the hibakusha. The woman who forgave a pilot who flew the plane that dropped the atomic bomb because she recognized that what she really hated was war itself. The man who sought out families of Americans killed here because he believed their loss was equal to his own.

My own nation’s story began with simple words: All men are created equal and endowed by our creator with certain unalienable rights including life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Realizing that ideal has never been easy, even within our own borders, even among our own citizens. But staying true to that story is worth the effort. It is an ideal to be strived for, an ideal that extends across continents and across oceans. The irreducible worth of every person, the insistence that every life is precious, the radical and necessary notion that we are part of a single human family — that is the story that we all must tell.

That is why we come to Hiroshima. So that we might think of people we love. The first smile from our children in the morning. The gentle touch from a spouse over the kitchen table. The comforting embrace of a parent. We can think of those things and know that those same precious moments took place here, 71 years ago.

Those who died, they are like us. Ordinary people understand this, I think. They do not want more war. They would rather that the wonders of science be focused on improving life and not eliminating it. When the choices made by nations, when the choices made by leaders, reflect this simple wisdom, then the lesson of Hiroshima is done.

The world was forever changed here, but today the children of this city will go through their day in peace. What a precious thing that is. It is worth protecting, and then extending to every child. That is a future we can choose, a future in which Hiroshima and Nagasaki are known not as the dawn of atomic warfare but as the start of our own moral awakening.

【2016.12.3 追記】

「オバマ氏、原爆資料館に手紙」 『2016.12.3 東京新聞』

ホワイトハウス

ワシントン

2016年11月21日

広島平和記念資料館

広島、日本

親愛なる友人たちへ:

みなさんの心からの贈り物をありがとうございます。ミシェルと私は、みなさんの寛容,寛大な行為に感動しました。

私は、核兵器のない世界へ向かって歩む、私の積極的関与を再確認するために、広島を訪れました。我々は歴史の見地をまっすぐ率直に見る共通の責務を持ち、また我々は再びかつての出来事、あの苦しみを(人々に)させない、違った(道を)必要とします。ヒバクシャによってせきたてられる戒めを通じ、戦争のための能力によるのではなく、我ら共有の人間性により、我々は我々自身の意味を明確にすることができるのです。あの破滅の日以来、我々は希望の選択をし、あなたたちの歴史は、我々がどれほど遠くへ来たかの、あかしなのです。より多くの人々が、過去を理解するための時間を取り、それを思いやり受容しさえすれば、より平和な未来が行く手に広がっていると、私は確信しています。

みなさんの思慮深い意思表示に、もういちど感謝します。みなさんの幸せを祈ります。

心から,誠実に(敬具)

バラク・オバマ

※ 映画『母と暮らせば』 ラストシーン撮影風景の、ニュース映像。

【2016.12.6 追記】

『対訳 アメリカの小学生が学ぶ歴史教科書 What Young Americans Know about History』

James M. Vardaman, Jr. と 村田薫 編 (ジャパンブック) から

【Pearl Harbor Pushes America to War】 (pp. 198-202)

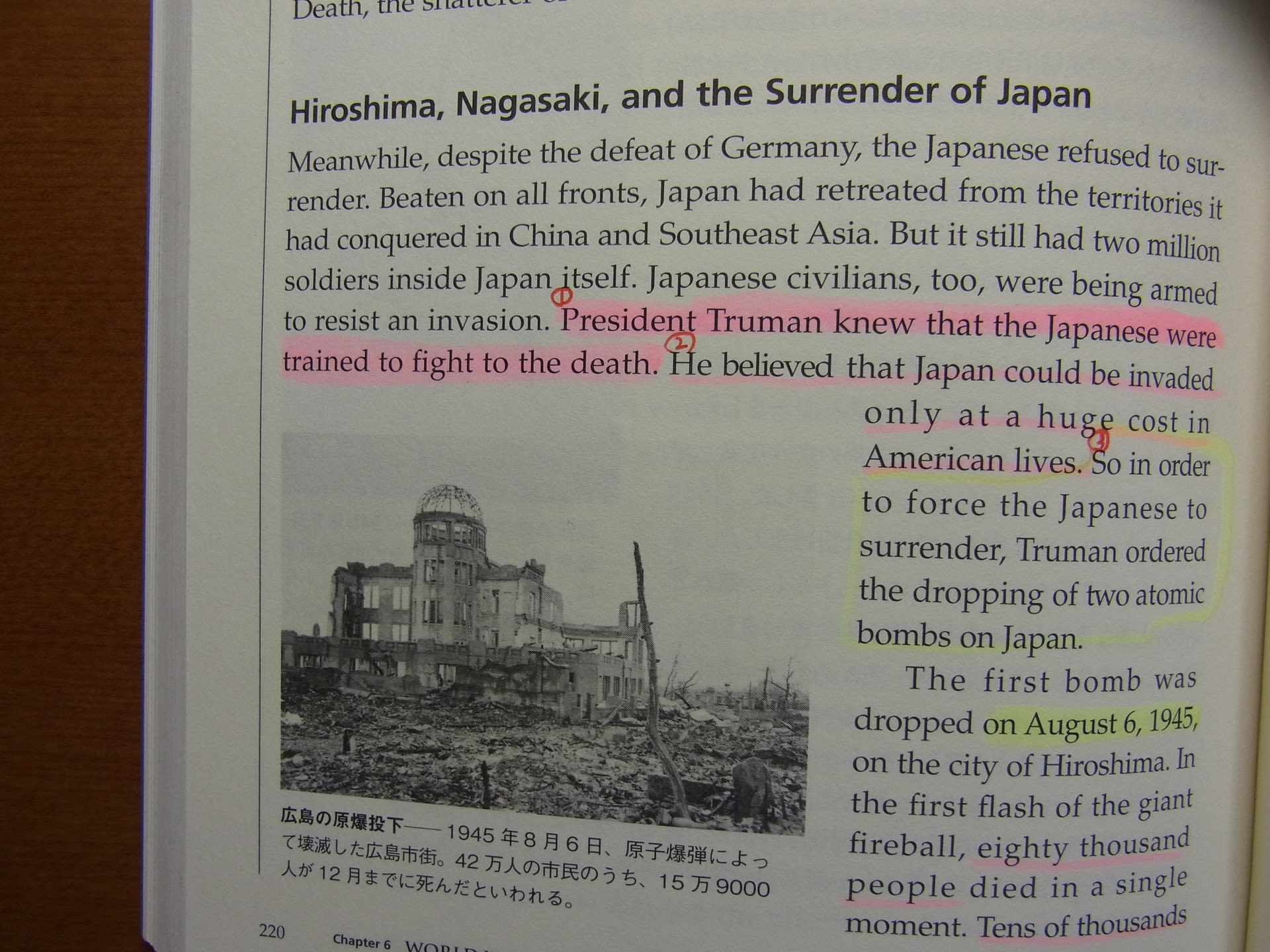

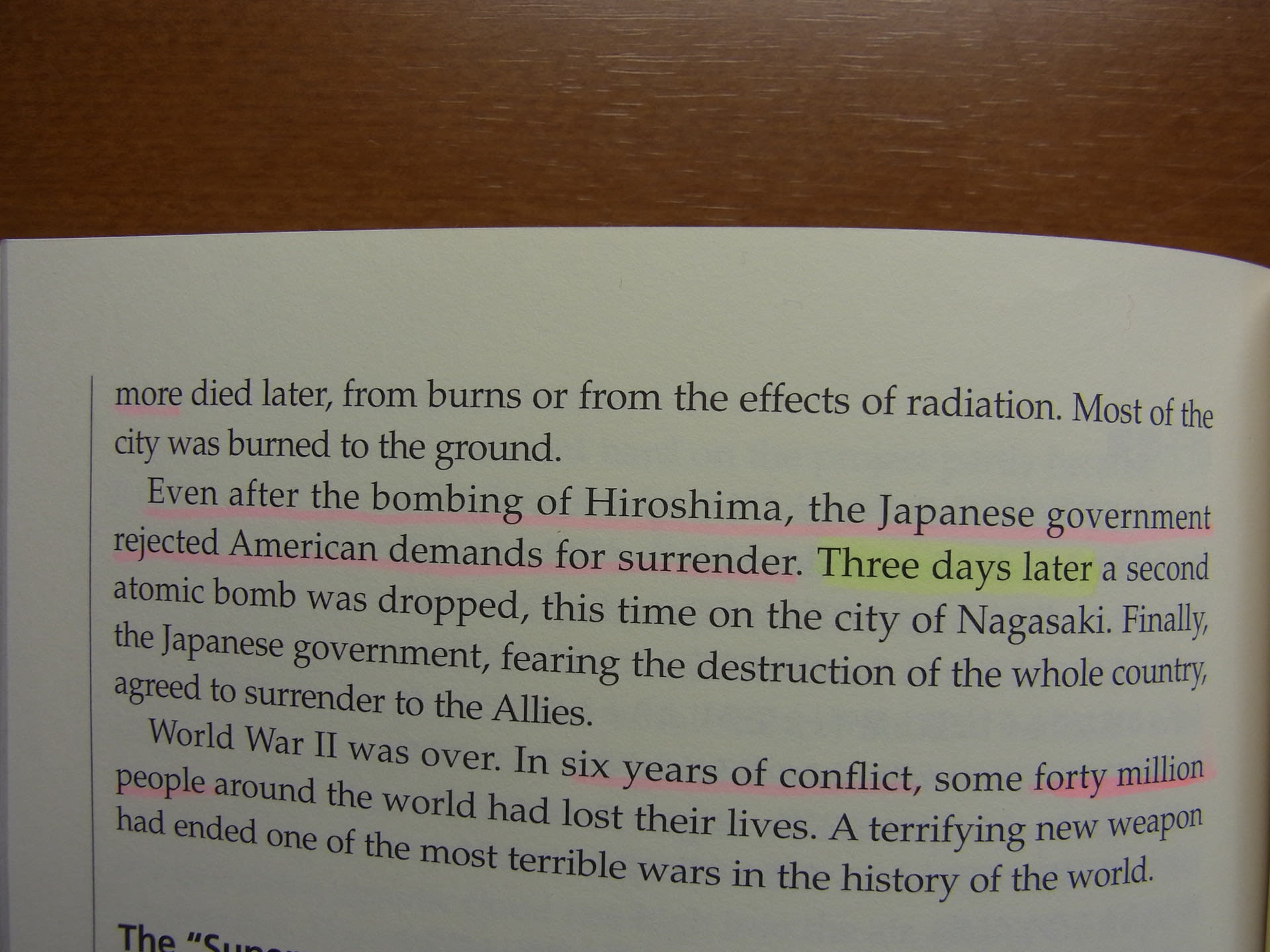

【Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the Surrender of Japan】 (pp. 220-222)

Why do we come to this place, to Hiroshima? We come to ponder a terrible force unleashed in a not-so-distant past. We come to mourn the dead, including over 100,000 Japanese men, women and children, thousands of Koreans, a dozen Americans held prisoner.

Their souls speak to us. They ask us to look inward, to take stock of who we are and what we might become.

It is not the fact of war that sets Hiroshima apart. Artifacts tell us that violent conflict appeared with the very first man. Our early ancestors having learned to make blades from flint and spears from wood used these tools not just for hunting but against their own kind. On every continent, the history of civilization is filled with war, whether driven by scarcity of grain or hunger for gold, compelled by nationalist fervor or religious zeal. Empires have risen and fallen. Peoples have been subjugated and liberated. And at each juncture, innocents have suffered, a countless toll, their names forgotten by time.

The world war that reached its brutal end in Hiroshima and Nagasaki was fought among the wealthiest and most powerful of nations. Their civilizations had given the world great cities and magnificent art. Their thinkers had advanced ideas of justice and harmony and truth. And yet the war grew out of the same base instinct for domination or conquest that had caused conflicts among the simplest tribes, an old pattern amplified by new capabilities and without new constraints.

In the span of a few years, some 60 million people would die. Men, women, children, no different than us. Shot, beaten, marched, bombed, jailed, starved, gassed to death. There are many sites around the world that chronicle this war, memorials that tell stories of courage and heroism, graves and empty camps that echo of unspeakable depravity.

Yet in the image of a mushroom cloud that rose into these skies, we are most starkly reminded of humanity’s core contradiction. How the very spark that marks us as a species, our thoughts, our imagination, our language, our toolmaking, our ability to set ourselves apart from nature and bend it to our will — those very things also give us the capacity for unmatched destruction.

How often does material advancement or social innovation blind us to this truth? How easily we learn to justify violence in the name of some higher cause.

Every great religion promises a pathway to love and peace and righteousness, and yet no religion has been spared from believers who have claimed their faith as a license to kill.

Nations arise telling a story that binds people together in sacrifice and cooperation, allowing for remarkable feats. But those same stories have so often been used to oppress and dehumanize those who are different.

Science allows us to communicate across the seas and fly above the clouds, to cure disease and understand the cosmos, but those same discoveries can be turned into ever more efficient killing machines.

The wars of the modern age teach us this truth. Hiroshima teaches this truth. Technological progress without an equivalent progress in human institutions can doom us. The scientific revolution that led to the splitting of an atom requires a moral revolution as well.

That is why we come to this place. We stand here in the middle of this city and force ourselves to imagine the moment the bomb fell. We force ourselves to feel the dread of children confused by what they see. We listen to a silent cry. We remember all the innocents killed across the arc of that terrible war and the wars that came before and the wars that would follow.

Mere words cannot give voice to such suffering. But we have a shared responsibility to look directly into the eye of history and ask what we must do differently to curb such suffering again.

Some day, the voices of the hibakusha will no longer be with us to bear witness. But the memory of the morning of Aug. 6, 1945, must never fade. That memory allows us to fight complacency. It fuels our moral imagination. It allows us to change.

And since that fateful day, we have made choices that give us hope. The United States and Japan have forged not only an alliance but a friendship that has won far more for our people than we could ever claim through war. The nations of Europe built a union that replaced battlefields with bonds of commerce and democracy. Oppressed people and nations won liberation. An international community established institutions and treaties that work to avoid war and aspire to restrict and roll back and ultimately eliminate the existence of nuclear weapons.

Still, every act of aggression between nations, every act of terror and corruption and cruelty and oppression that we see around the world shows our work is never done. We may not be able to eliminate man’s capacity to do evil, so nations and the alliances that we form must possess the means to defend ourselves. But among those nations like my own that hold nuclear stockpiles, we must have the courage to escape the logic of fear and pursue a world without them.

We may not realize this goal in my lifetime, but persistent effort can roll back the possibility of catastrophe. We can chart a course that leads to the destruction of these stockpiles. We can stop the spread to new nations and secure deadly materials from fanatics.

And yet that is not enough. For we see around the world today how even the crudest rifles and barrel bombs can serve up violence on a terrible scale. We must change our mind-set about war itself. To prevent conflict through diplomacy and strive to end conflicts after they’ve begun. To see our growing interdependence as a cause for peaceful cooperation and not violent competition. To define our nations not by our capacity to destroy but by what we build. And perhaps, above all, we must reimagine our connection to one another as members of one human race.

For this, too, is what makes our species unique. We’re not bound by genetic code to repeat the mistakes of the past. We can learn. We can choose. We can tell our children a different story, one that describes a common humanity, one that makes war less likely and cruelty less easily accepted.

We see these stories in the hibakusha. The woman who forgave a pilot who flew the plane that dropped the atomic bomb because she recognized that what she really hated was war itself. The man who sought out families of Americans killed here because he believed their loss was equal to his own.

My own nation’s story began with simple words: All men are created equal and endowed by our creator with certain unalienable rights including life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Realizing that ideal has never been easy, even within our own borders, even among our own citizens. But staying true to that story is worth the effort. It is an ideal to be strived for, an ideal that extends across continents and across oceans. The irreducible worth of every person, the insistence that every life is precious, the radical and necessary notion that we are part of a single human family — that is the story that we all must tell.

That is why we come to Hiroshima. So that we might think of people we love. The first smile from our children in the morning. The gentle touch from a spouse over the kitchen table. The comforting embrace of a parent. We can think of those things and know that those same precious moments took place here, 71 years ago.

Those who died, they are like us. Ordinary people understand this, I think. They do not want more war. They would rather that the wonders of science be focused on improving life and not eliminating it. When the choices made by nations, when the choices made by leaders, reflect this simple wisdom, then the lesson of Hiroshima is done.

The world was forever changed here, but today the children of this city will go through their day in peace. What a precious thing that is. It is worth protecting, and then extending to every child. That is a future we can choose, a future in which Hiroshima and Nagasaki are known not as the dawn of atomic warfare but as the start of our own moral awakening.

【2016.12.3 追記】

「オバマ氏、原爆資料館に手紙」 『2016.12.3 東京新聞』

ホワイトハウス

ワシントン

2016年11月21日

広島平和記念資料館

広島、日本

親愛なる友人たちへ:

みなさんの心からの贈り物をありがとうございます。ミシェルと私は、みなさんの寛容,寛大な行為に感動しました。

私は、核兵器のない世界へ向かって歩む、私の積極的関与を再確認するために、広島を訪れました。我々は歴史の見地をまっすぐ率直に見る共通の責務を持ち、また我々は再びかつての出来事、あの苦しみを(人々に)させない、違った(道を)必要とします。ヒバクシャによってせきたてられる戒めを通じ、戦争のための能力によるのではなく、我ら共有の人間性により、我々は我々自身の意味を明確にすることができるのです。あの破滅の日以来、我々は希望の選択をし、あなたたちの歴史は、我々がどれほど遠くへ来たかの、あかしなのです。より多くの人々が、過去を理解するための時間を取り、それを思いやり受容しさえすれば、より平和な未来が行く手に広がっていると、私は確信しています。

みなさんの思慮深い意思表示に、もういちど感謝します。みなさんの幸せを祈ります。

心から,誠実に(敬具)

バラク・オバマ

※ 映画『母と暮らせば』 ラストシーン撮影風景の、ニュース映像。

【2016.12.6 追記】

『対訳 アメリカの小学生が学ぶ歴史教科書 What Young Americans Know about History』

James M. Vardaman, Jr. と 村田薫 編 (ジャパンブック) から

【Pearl Harbor Pushes America to War】 (pp. 198-202)

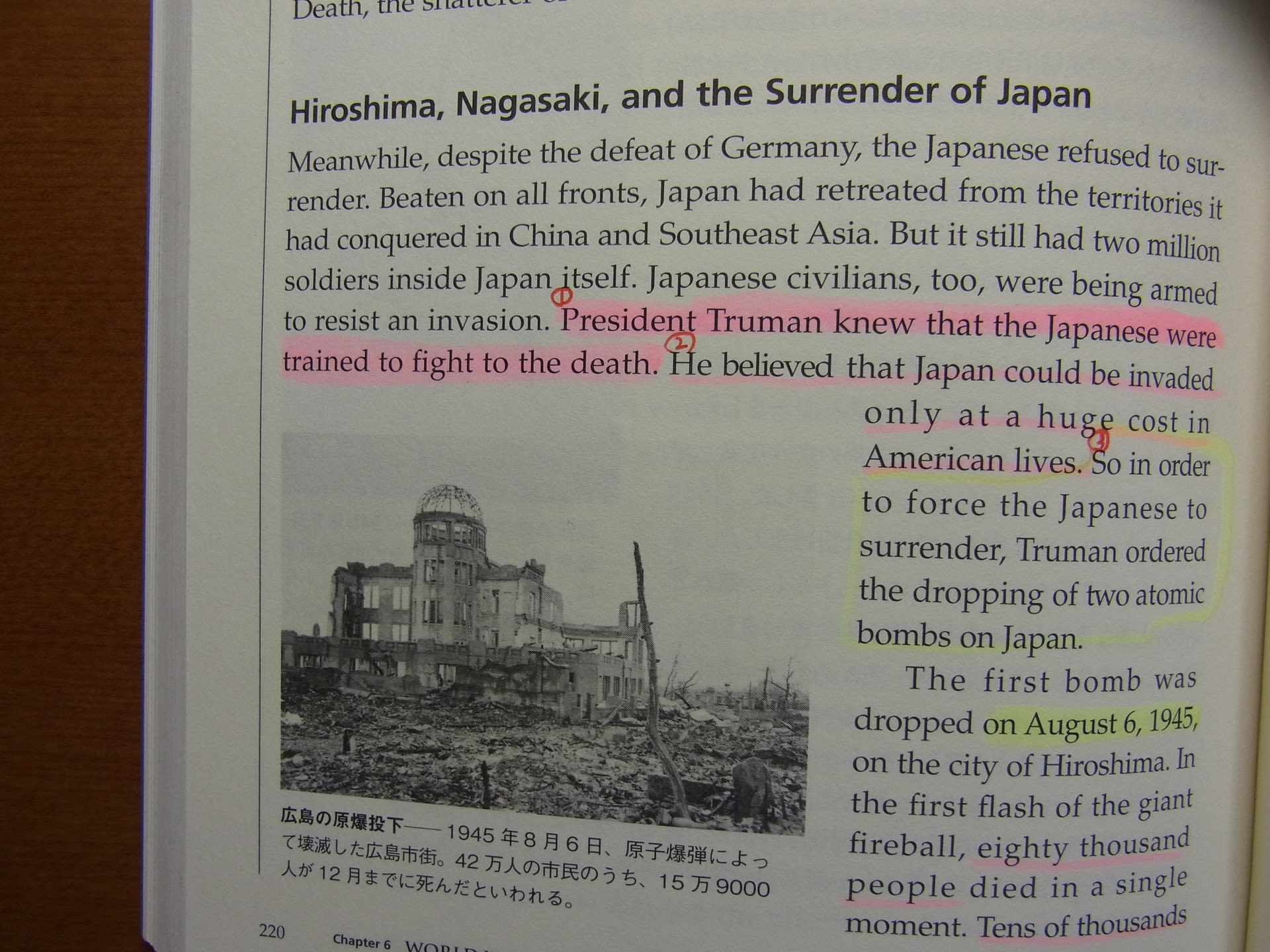

【Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the Surrender of Japan】 (pp. 220-222)