今回、レクチャーでは何を話されたんですかー?

と訊かれるんですが、実はかなり過激なことを話してきました。

よく言えば奔放、悪く言えば否定的。

でもこれ、liberty だの radical だのと言ってしまえば、イメージ的にはかなり 軟化しちゃうので

けっこう言いたいことを言っても、それほどキツくは響きません。

そういう意味では、英語ってかなり便利な言葉。

で、何を言ってきたかというと、

要するにポジャギとは元来、包むことによって大切なものを保護するものであり、

装飾によって邪悪を封じる、謂わば「武装」であり闘いであったのだと。

かつての人たちが持っていたその強靭さを、現代においてどう表現するかが

私にとっての課題なのだ…(つまり、ただきれいなだけでは意味ないのだ)

みたいなことを、一席(~_~;)

最も言いたかった一言が、”even more savage”という表現で

言ってみれば、これを説明したいがために前後左右の文章があるわけですが、

どこまで(私なんぞの発音で)わかっていただけたかなあ。

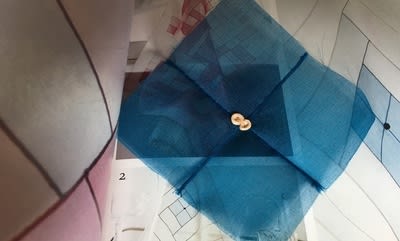

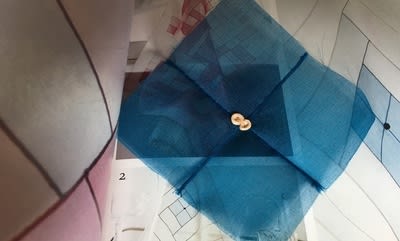

それはさておき、今回の作品展で一番人気を争ったのが、なんと最も古いコレと

最も新しい(なにしろ、まだ🍊)のコレだったのは意外、というか痛快でした。

自分のことばかりで申し訳ありません。次回は海外作家の方のお話など(^^)

Bojagi as my artistic medium

Yoko Kubota

First of all, I would like to thank all the KBF members, especially Ms. Chunghie Lee who invited me here. I am truly delighted to see you as one of the Bojagi artists in Japan. As you know, my English is too poor to express my opinion. So please forgive me. After that, I would like to start by meeting Bojagi.

It was around 1995, when I was interviewing some antique shops about Korean furniture. In the very last few years of 20th Century, I think it was after Seoul Olympic, maybe, Korean traditional furniture or ceramics, especially of the Yi Dynasty, was experiencing a little boom of popularity in Japan, and I had to write some articles about them for magazine. Under such circumstances, I encountered Bojagi for the first time. Bojagi, which I saw there, was a small napkin-like cloth (Taguabo/다과보) composed of complicated lines and several colors. It was so beautiful and powerful.

But, at that time, I recognized it as a kind of antique item because it was placed at a corner of the antique shop, as if left behind. Also in that shop, I found a book, The Wonder Cloth (The Museum of Korean Embroidery, 1988)1. With this great book, I was able to learn what Bojagi was and what kinds of social and traditional meaning it had, also its usage and how it was made. By the way, this book was quite expensive, but I did I not hesitate to buy. Perhaps it was my destiny, I think.

In the following years, Bojagi was still an antique for me. But suddenly, it appeared before us, as pieces reproduced in modern times. In 1999, Ms. Kim Hyun Hee, who was recognized as a master of embroidery and Bojagi, published Korean Patchwork POJAGI 『韓国のパッチワーク ポジャギ』(文化出版局)2. It’s on how to make Bojagi, introducing the technique for the first time in Japan. This book had a great impact on us. Because even though we knew of the existence of Bojagi, most of us thought that it was only relic of the past, and never thought that it was being made right now.

Therefore, it can be said that Bojagi making in Japan basically started with this book. It can be said that it was a very happy encounter for us. Because, at the beginning, we were able to see authentic masterpieces, not copies or imitations. I think that in originality and completeness, it is difficult for us to find a textbook that exceeds this. On the other hand, the first generation of Bojagi in Japan was inevitably placed under the influence of Ms. Kim Hyun Hee.

After all, Japanese are foolishly serious and precise, so that we had come to believe that finely aligned stitches, colors by natural dyeing, well-organized designs, in short, all of her characteristics are indispensable for Bojagi. (However, it did not take so long for us to realize that it was not necessary to think so……) But anyway, we, the first generations were more or less, her loyal followers.

Immediately after entering the 21st Century, an unprecedented Korean boom (Hanryu Boom) occurred in Japan. Since this boom originated from a big hit by TV drama, the boom itself was not directly related to Bojagi, but as the general interest in Korea has increased, more handicraft enthusiasts began trying to make Bojagi.

For a while, it was even said that the popularity of Bojagi was higher in Japan than in Korea. But here, one big misunderstanding existed. Somehow, at the very biggining, many Japanese have equated Bojagi with Chogappo (조각보/patchwork). For them, any items made by technique of Chogappo , such as pouches, pincushions, and coasters, were all “Bojagi”. And this trend, for the most part, continues today. Such a misunderstanding is not a big problem, as it’s only a nickname ―― Maybe, many people would say so.

However, I think that the philosophy of Japanese Bojagi is the best represented as follows. It seems that preference of Bojagi for Japanese enthusiasts is: 1: sweet and gentle colors, 2: transparent feeling of thin silk and moshi(모시/ramie), and 3: neat patterns created by advanced sewing techniques. In making Bojagi, they accurately measure the size of Chogappo , thinking about the balance of colors, never using colors that disturb the total harmony, and respect the ordered stitches. If there is a sample, they would try to make it as precisely as possible.

Because of such integrity and effort, their pieces are usually neat without any breakdown. Of course, I am not objecting. And I am not interested in denying handicrafts as everyday pleasures, conversation pieces, or cute, small goods that are suitable for gifts.

However, unfortunately (or perhaps fortunately), my first impression of Bojagi was not only its beauty. Not only beauty, but of the intense power of trying to protect something what is wrapped there. Trying to protect very important something.The most important role of Bojagi was “protect something”. And so, as a primitive meaning for every decoration was, that is as an ”amulet,” or a protection in the fight against all kinds of evil.

It goes without saying that Bojagi, especially Chogappo were made for ages by countless unknown women belonging to the common class. For them, family and home were all they knew of the world, and protecting the household was everything in life.

Yes, Bojagi was a kind of “armor” to protect their most precious things. Therefore, the existence of Bojagi should have been much stronger, exciting, even more savage than we thought. It should have had much more power than we thinking in modern times.

Looking back now, it may have been fortunate that the first Bojagi I met was an antique item. Because I was able to directly understand the intrinsic power of Bojagi. And that power is nothing less than a common motivation for all kinds of art.

I believe that all of you are inspired by the intrinsic power of Bojagi. No matter what kinds of expression. In other words, unless I can feel such power, it is not Bojagi, at least for me. No matter how beautiful or elegant it is.

Excuse me, I may have been a little excited. What I said now is a commandment against myself, not a criticism of others.

Finally, I will talk a little about my own works. It was not only the power of the colors and strength of the lines, but also the freedom of the designs that attracted me. In a very limited range of living, how did women come up with such wild and fancy designs? It is because, whether they were conscious or not, such “freedom” was what they truly wanted in the depths of their hearts, and because Bojagi became the “medium” to express their souls.

Also for me, Bojagi is a medium for expression of myself, exceeding the frame of traditional Korean handicraft. I feel unbounded liberty in Bojagi, as various painters find unlimited potential in the space of the white canvas, or orchestra conductors create astonishingly colorful music from one score. Over the past decade I have been pursuing the possibilities of composition with lines. Color is of course important, but at the moment, I am interested in producing complex expressions with few colors or a single color as well as possible. (O Bang Saek) 3

The last green one is still unfinished, but at the exhibition hall, I intend to demonstrate with this.

Now, I am making Bojagi in a perfectly free position. I do not have any master to obey and no group to maintain. My teachers are past wonderful pieces, and powerful artworks born from various cultures, for example, Gees Bend4, African Kuba art,5 Improv patchwork6……and of course, the wonderful works and trials of KBF members. Maybe, I am walking in a somewhat different path than the so-called handmade creators in Japan. However, there is no doubt that I am extremely passionate about making Bojagi.

Thank you for your kind attention.

Photos

1 The Wonder Cloth Huh Dong-hwa The Museum of Korean Embroidery(1988)

2 『ポジャギ』金賢姫 文化出版局 (1999)

3 O Bang Saek (5 pieces)その他

4 Gee’s Bend The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Tinwood Alliance(2006)

5 『アフリカンデザイン』渡辺公三/福田明男 里文出版 (2000)

6 Improv Patchwork María Shell Stash Books (2017)