ヤンソンスさんが30日夜にサンクトペテルブルクのご自宅で亡くなられたことを、昨夜知りました。

長年の心臓の持病が原因の心不全だったとのこと。

自分でも意外なほどの寂しさと喪失感を感じてしまっていて、今日は一日ぼんやりと過ごしてしまいました。あの3回の演奏会でヤンソンスさんからいただいたものが私にとってどれほど大きかったかということを、じわじわと思い知らされています。

3年前の川崎公演は友人も同じ会場で聴いていました。たった3年の間に友人もヤンソンスさんもいなくなってしまうなんて、なんだか夢をみているような気がします。そして一人の人がこの世界からいなくなるということはこんなにも世界が違って感じられるものかということを、改めて感じています。

皆さんが様々な追悼文や想い出をSNSにあげられていますが、私の場合は最後の来日公演のときの感想記事が一番ヤンソンスさんへの感謝の気持ちを伝えられるように思うので、ここにリンクを貼らせてください。

2016年11月26日 『R.シュトラウス:アルプス交響曲』他 @ミューザ川崎

2016年11月27日 『マーラー:交響曲第9番』 @サントリーホール

2016年11月28日 『ストラヴィンスキー:火の鳥』他 @サントリーホール

Mariss Jansons 1943 - 2019

昨日掲載された、バイエルン放送響による追悼動画です。

彼らが”Love song to life and mortality”、”Hymn to the end of all things”と呼んでいたマーラー9番の、最後の9分間の演奏です。

上記記事にも書きましたが、サントリーホールで聴いたヤンソンスさん&BRSOによるこの曲の演奏は、この世界に生まれ、やがて死んでいく全ての生きとし生けるものにヤンソンスが贈ってくれた慈愛の歌であるように感じられました。

公演の後、ヤンソンスさんはインタビューでこんな風に仰っていました(独語からのgoogle翻訳です)。

――Mr. Jansons, you and your orchestra have made people cry in Tokyo with Mahler's Ninth. You, too, have been taken very seriously. Can you feel death in this piece?

Jansons:

Absolute! You can imagine the music in such a way that a person lies in bed and knows that his death is coming soon. He does not know when, but he comes. And then he remembers almost his entire life: moments that made him happy, moments that were difficult and tragic for him. It's a retrospective to the end. I feel that death comes sooner than the end of the fourth sentence. The cellos play their last notes, then I take a big break, and then the strings play this incredible music, where you can really cry. For me, this music is no longer on earth, there Mahler's soul is already in heaven - and we feel his spirit and his genius that remain for us on earth.

もしヤンソンスさんに最後に聴こえていた音楽があったとしたら、このマーラー9番の最終楽章だったのではないかと思えてなりません。

BRSOはヤンソンスさんの逝去の報に「We are devastated.」とコメントをしています。来日公演最終日のアンコールでヤンソンスさんが舞台上で転倒したとき、ショックを受けた表情を最後まで消すことができないでいたのは誰よりオケの人達だったことを思い出します。そんな彼らを安心させるようにおどけて笑ってみせたヤンソンスさんの姿も、昨日のことのように覚えている。

2003年の首席指揮者就任時からずっと尽力されてきたミュンヘンの新ホールに響く彼らの音、ヤンソンスさんに聴かせてあげたかったなあ…。BRSOの方達も、どれほどヤンソンスさんと一緒にその日を迎えたかったろうと思います。

長い間爆弾を抱えた体で音楽に献身されてきたヤンソンスさん。

あなたがくださった音楽はこの先の人生でどれほど私を励まし続けてくれることでしょう。

どんな感謝の言葉も足りません。

本当にありがとうございました。

どうか安らかにおやすみください。

2016年11月28日、来日公演最終日のソロカーテンコール。BRSO twitterより。

#5 Asia 2016: Jansons dirigiert Mahler 9 (Ausschnitt)

2016年11月27日、サントリーホール。マーラー9番の最終楽章冒頭の映像。

今気づきましたが、BRSOの追悼動画に使われている映像はこの日のもの、ですよね…?映っている物や角度が全く同じだもの…。音もこのときのものだ…。コンマスさんが"It was a historical concert for our orchestra"と仰っていたこの日の演奏。ヤンソンスさんが愛した"BRSOのピアニシモ"。

だめだ、涙がでる……。

BRSOはいつかフルの映像をあげてくださらないだろうか…。

Happy Birthday, Maestro!

2016年1月14日のBRSOからヤンソンスへの73歳のバースデーサプライズ。

ヤンソンスさんもオケもとても幸せそう。

If you tell someone, "I love you," then you can not say it neutral, it demands something different from human beings. It's absolutely the same in music!

(Symphonies like a "I love you": Dec 13, 2016)

※コンセルトヘボウからもメールが届きました。

BRSOもRCOも12月1日と発表していますが、メディアの情報によると11月30日の夜遅くに亡くなられたようです。

On Sunday December 1 our beloved conductor emeritus Mariss Jansons died in St. Petersburg. Mariss Jansons was chief conductor of the Concertgebouw Orchestra from September 2004 up to and including the 2014/2015 season, after which he was regularly a guest.

The music world not only loses a great conductor, but also a warm and honest person. We sympathize with his dear wife Irina and his family and loved ones.

※Het Concertgebouw twitterより

We look back with gratitude and pride on the wonderful concerts of #MarissJansons in The Concertgebouw and what he has meant for The Concertgebouw and the Concertgebouw Orchestra. This photo is of the last concert that he conducted in the Grote Zaal on 22 March with @BRSO

※RCOからヤンソンスさんへの追悼の演奏

ヤンソンスさんがアンコールで好んで演奏していたという『悲しきワルツ』。美しいですね。。。

In memory of our conductor emeritus Mariss Jansons we play one of his most beloved encores, the Valse triste by Sibelius. Dear Mariss, rest in peace.

※ジャパンアーツtwitterより

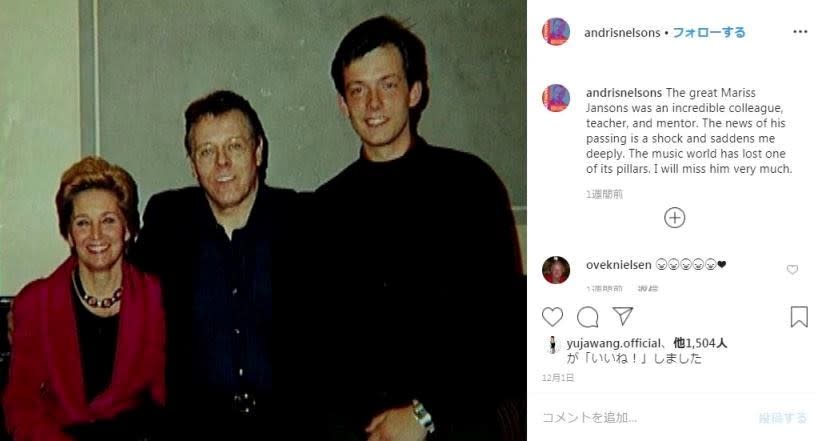

※ネルソンスのインスタより

【過去のインタビュー等より抜粋】

※

-You still seem eager to learn.

Oh yes. There is always something new to learn. That’s why I go to my colleagues’ rehearsals as often as possible. It is so interesting and enriching to watch Haitink, Harnoncourt, Rattle, Muti, Barenboim, and many others, at work! It is very important to question not only tradition but also your own convictions.

・・・

-What would be the greatest virtue in a conductor?

Honesty.

-That is a human virtue, not a musical one.

Honesty is necessary both for humanity and for music.

(An Interview with Mariss Jansons, November 2012)

※

'If the public says to you after the concert, "Oh my God, I was in heaven for two or three hours"―then you know it was one of those cosmic concerts. But if somebody says, "It was a very good concert, the orchestra played very well, there were nice tunes, it was very polished," then it is not right. That is the difference between a very good concert and one of those excellent concerts. But of these excellent concerts, there are not so many.'

(Tom Service "Music as Alchemy: Journeys with Great Conductors and their Orchestras")

※

Mr Jansons, in an interview with our newspaper in 2009 you said: I will fight for a new concert hall in Munich, even if it takes until 2020.

Mariss Jansons: You know, it is now clear that the hall will be built. I can't say now I don't care how long it takes. Absolutely not. If you build like in Hamburg, it's a disaster. You have to check that all the time! This is not my first task, but you have to initiate a little. But the main thing is that the decision is made!

At that time you said that you would like to open the hall as chief conductor. Your contract runs until 2021.

Jansons: Of course, that's right. But I don't think that will happen. The builder said he believes the hall will be finished in 2023/24.

That would be a good reason to hang on for two or three years?

Jansons: Yes, I'm not sure about that. I do not know. You know, I've been here a long time. I absolutely cannot tell you that. It depends on the relationship we have in the orchestra. If that's still fresh, lively and interesting, then maybe. But if you say: Thank you, we have had a fantastic time together, now a new direction has to come, then you have to say: Thank you very much! Otherwise we play and they fall asleep in the audience (laughs). You have to understand when it's time. Fortunately, conductors live very long. But I don't want to sit in the chair like a clown when conducting and falling asleep. You have to feel when it's time.

How do you spend the day on tour to always have enough energy?

Jansons: On concert days I try - that does not mean that it always works - not to arrange meetings, not to give interviews and to save my energy. And after lunch I go to sleep. When I get up again, I'm absolutely focused on the work and the performance. Then there is no phone and no distraction anymore. Now comes a difficult moment on the tour: At the beginning everything is very fresh and everyone is excited, then the second and third and fourth concerts come, and then it is very dangerous that the routine comes. Routine is the most dangerous thing! I know what I'm talking about: we had incredibly long tours with the Leningrad Philharmonic, sometimes up to two months with at least 25 recordings. From where do you get the emotion and tension of the 16th Tchaikovsky Symphony in a row?

Where do you get them from?

Jansons: When you conduct, you always have to remember that your first task is to inspire the orchestra. If they don't inspire it, it's routine and boring - even for the orchestra. It is bad if you inspire and the musicians don't inspire you back. That happens sometimes, but luckily not with our orchestra. I just have to light the fire with the match and they make a big fire out of it. But as a conductor you have to light it.

You and your orchestra made people cry in Tokyo with Mahler's Ninth. You, too, looked very battered. Do you feel death in this piece?

Jansons: Absolutely! You can imagine the music so that a person lies in bed and knows that his death will soon come. He doesn't know when, but he's coming. And then he remembers almost his whole life: moments that made him happy, moments that were difficult and tragic for him. It's a retrospective to the end. I feel that death comes earlier than the end of the fourth sentence. The cellos play their last notes, then I take a big break, and then the strings play this incredible music, where tears really come. For me this music is no longer on earth, Mahler's soul is already in heaven - and we feel his spirit and ingenuity, which remain on earth for us.

Your orchestral musicians say they feel a very strong emotional bond with you when you conduct and read a lot on your face. Can you describe what is happening there?

Jansons: I don't know what I'm doing with my face. I only know that when I conduct, I do not only conduct notes and signs and dynamics and ensemble sound. I try to show what kind of atmosphere there is, what is happening, what the composer wants to express - or what I want to express. But that's abstract. So if I feel that there is something malicious in the music, for example, my face might show that too. It is the same with speaking: we make movements, our eyes react - neither of us are sitting here like the mummies. And that's much stronger in music. When that hits the musicians, it makes me happy.

How do you convey this emotion to the orchestra?

Jansons: It doesn't matter whether you conduct a little longer or further, or whether you communicate with your hands or eyes. But the conductor has to feel the charisma and character of the music, it has to come, you understand? Instinctively! And if it doesn't come instinctively, it means that he has no connection to this music. If you say "I love you" to someone, then you cannot say it neutrally either, that requires something different from human beings. It's absolutely the same in music!

("You have to feel when it's time" December 13, 2016)

※

Mariss Jansons’ earliest musical memories are largely operatic ones. He was born in Nazi-occupied Riga in 1943, son of the great Latvian conductor, Arvīds Jansons, and soprano Iraida Jansone. When Mariss was only three, his father was chosen by Yevgeny Mravinsky to be his Assistant Conductor at the Leningrad Philharmonic. The rest of the family eventually joined him in Leningrad ten years later, where the young Mariss would succeed his father as Mravinsky’s assistant, then Yuri Temirkanov’s, at a time of great transition in the former Soviet Union. Russia is still Jansons’ home – “I have the brain of a Latvian and the heart of a Russian” he recently stated – and he speaks to me on the phone from St Petersburg.. We begin our conversation by reflecting on his childhood.

・・・

Did the heart attack change his approach to making music?

“Oh yes, very much. In such a moment when you are between life and death, you start to analyse what life actually is. Why are we here? What is important? I’m not Mahler, but I’ve raised for myself these questions that Mahler asks many times in his symphonies. I feel I’ve become much richer, a more profound musician, better at fulfilling slow tempos. I can’t say it’s completely changed my mentality but it’s given me new characteristics, new perspectives.”

Early this century, Jansons took the helm of not one, but two of the finest European orchestras, the BRSO and the Royal Concertgebouw. When asked about their respective qualities, he reflects on excellence in orchestral playing. “When you think about the Berlin Philharmonic, the Vienna Philharmonic, the BRSO, the Concertgebouw, the level is so high. Everything is first class. There was a ranking in Gramophone but it’s very difficult to do that in music… it’s not like sport. This group of leading orchestras is very special. The BRSO is a very spontaneous orchestra, very virtuosic, with a German sound, a cultivated sound and they can play wonderful pianissimos. In Amsterdam, meanwhile, there’s an intelligent sound, well balanced. Both orchestras have their individualities but both play at the highest level.” We pause to discuss the internationalisation of orchestral sound – “this comes through recordings and what you can do with microphones” – before considering the role of the conductor as a guardian of an orchestra’s character.

“When I went to Amsterdam and Munich,” he explains, “there were many journalists asking me what I wanted to change. I said ‘I don’t want to change anything, because they are great artists and great personalities. If they can learn something from me and I can learn something from them, then this will naturally evolve in a new direction.’”

("From Riga to Munich: Mariss Jansons on his musical journey" bachtrack, April 18, 2018)

「オーケストラの音の個性を自分に合わせて変えようとは思わない」。ハイティンクも同じことを仰っていましたね。

※

It's 20 years since Mariss Jansons, 74, had a heart attack while conducting La Bohème. A year of enforced rest followed. Since then his friends and advisers have pleaded with him to stick to an austere diet and go easy on his workload. Cheerfully, almost fatalistically, he carries on just as before. “I know I must reduce my work, but I can't do it,” he says. “When I have free time I always feel ill. The tension goes, my immune system stops, and I get sick. So work keeps me alive!” Not, perhaps, the most scientific of diagnoses but thousands of music-lovers round the world will be grateful that Jansons believes it. At least he now has only one orchestra to fret about. For a decade until 2015 he was chief conductor of two of Europe's best, simultaneously: the Royal Concertgebouw in Amsterdam and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra in Munich. The clashes of repertoire, tours and everyday demands were insane. Yet when Jansons bowed to the inevitable and dropped one of them he surprised everyone by sticking with the less famous Bavarians — the orchestra he brings to London on April 11.

・・・

It's unlikely that the hall will be finished before 2024, which means that it may be built at the same time as the Barbican builds its proposed new concert hall in London. What a fascinating comparison of budgets, design, acoustics and efficiency that might make. “Perhaps I won't be around in 2024,” Jansons muses, “but I will know that at least once in my life I did something important for Munich and my orchestra.”

(”Mariss Jansons, the maestro with the magic touch”, The Times, April 10, 2017)

※

-One core feature of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra brand is that it often gives invitations to guest conductors, including many famous ones with their personal touch. How do you nevertheless manage, as principal conductor, to maintain supremacy over the orchestra’s sound?

I don’t intervene at all in the work of the guest conductors. I’m not even present. Actually, guest conductors tend to support my efforts: the better they are, the more the orchestra learns from them, and the better we become. What I aspire to do is hard to put into words without sounding banal: the orchestra must play well – in a technical sense. The intonation must be flawless, and I put great store in sound.

-What does the orchestra sound like?

Quite good, I think (laughs). We have a very full sound, very emotional, brilliant and dark, the full spectrum. What pleases me most is our pianissimo: it’s easy to play soft, but extremely hard to sound vibrant and expressive at the same time. This orchestra can do it.

・・・

-When you conduct a concert, how often are you satisfied with what you hear? Do you ever think, “Now it’s perfect”?

There’s no such thing as “perfect.” To be honest, I don’t waste much thought on that during a concert. Of course I have to analyze what’s happening when I conduct; I can’t focus simply on emotions and expression. But emotions have top priority. Besides, it’s too late to correct anything. Once I’ve heard it, it’s over. There’s time for analysis after the concert. Then I can consider what was good, what I have to watch out for next time, and what part of the sound I’d like to change.

-A tightrope walk between gut, heart, and brains.

Then I’m in my own inner world, somewhere between feeling and reason – I can’t pin it down more accurately than that. But in any case I have to be fully involved in this process if the music is to emerge. If I think too much about what already happened, the things yet to come can easily go wrong because I’m not focused on them. I have to foresee what’s coming and prepare it in my mind.

-In such moments, does your initial ideal sound still play a role?

It can well happen that I spontaneously decide to try out something new, especially on tour, when we play a work four or five times. Then I’m very fond of improvising a bit. The musicians know this, and of course I take care not to exaggerate so that things don’t get out of hand. Besides, I don’t like it when a concert simply replicates the rehearsal. A concert must be more than that. It’s like a rocket: the first stage is the preparation, the second the rehearsals in the hall, but there still has to be a third stage if it’s to reach the cosmos – namely, the best I can give, combined with the best the orchestra can give.

(”Interview wish Mariss Jansons: Wish and Reality", BRSO)

※

The 1996 heart attack that nearly killed him was almost a case of history repeating itself. His father, too, had a heart attack while performing, in 1984; his was fatal. Mr. Jansons said his own near-death experience changed him musically.

“Of course, you start to analyze what is important in life, really, and what is a priority, and how to divide your time and calculate your energy,” he told The Times in 1997. “But then something comes unconsciously, and this is what I felt in music. I started to like calmer music, quieter music. I like slower tempos. I enjoy it more, because I enjoy, perhaps, a more philosophical approach.”

("Mariss Jansons, Who Led Top Orchestras, Dies at 76", The New York Times, Dec 2, 2019)

※

It was April 25, 1996, three months after his 53rd birthday. Jansons later attributed his survival to the emptiness of the Oslo streets through which he was driven to hospital. The omens were not good: 12 years earlier his father, Arvid Jansons, had died aged 70 after suffering a heart attack while conducting the Hallé Orchestra in Manchester.Jansons Jr had a second heart attack a few weeks later, but doctors declared his arteries too frail for a bypass. Instead they prescribed a year’s recuperation in Switzerland, not an easy prospect for a conductor brimming with ideas and enthusiasm. Yet it was a period that turned him from a precocious firebrand into a mature maestro. Later he would be fitted with an internal defibrillator.

A specialist in Russian music, notably that of Tchaikovsky, Prokofiev and Shostakovich, Jansons rode to prominence with a little-known Norwegian orchestra that found fame with him. Richard Morrison in The Times said that orchestral musicians revered him for three reasons: “He is genuine. He is genial. And he is a genius.”

・・・

During the early years of this century Jansons gave memorable accounts at the Proms of Dvorak’s Ninth Symphony, Tchaikovsky’s Fourth and Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique. Yet regardless of the venue, Jansons wanted every performance to be a special event. “A concert should be something extraordinary, what I call cosmic,” he said. And for many appreciative audiences they were just that.

Mariss Ivars Georgs Jansons was born in German-occupied Riga, the capital of Latvia, in 1943 while his Jewish mother, Iraida, was in hiding because her father and brother had been killed in the ghetto. As a toddler he would watch Iraida, an opera singer, rehearse Carmen: “In the first act, when José took her and put the handcuffs on to take her to prison, I was shouting out, ‘Don’t touch my mother!’ and I started to cry because I thought they were really taking her away.”

He studied violin with his father and began conducting a toy orchestra. “It started when I was four or five,” he said. “I made an orchestra of buttons, of paperclips, and rubber erasers — thousands of things — and I would conduct concerts.” There was a near digression when he was spotted displaying skill at football by the Latvian national coach. “Football?” his mother screeched in horror. “Are you crazy? He is going to be a musician.”

・・・

Through it all he retained his Soviet-era humour. On one occasion he was entertaining a Times journalist in Pittsburgh, but had neglected to book a table at his favourite restaurant, which turned out to be full. He asked to speak to the manager, who recognised him and conjured up a table overlooking the river. “See,” Jansons said, beaming with pride. “Just like in the Soviet Union.”

(”Mariss Jansons obituary”, The Times, Dec 2, 2019)

※追記:

Muziek uit hart en ziel: Mariss Jansons (1943-2019) door Thiemo Wind

コンセルトヘボウが12月11日に掲載してくれた、亡くなる9日前の電話インタビュー。コンセルトヘボウとのブルックナー8番の演奏予定について。