●小林恭子の英国メディア・ウオッチ : Nファーガソンが描く、2021年のユーロ・欧州像が面白い 2011年 12月 11日

スコットランド出身の歴史学者N・ファーガソンが、米ウオール・ストリート・ジャーナル紙に書いた記事「2021:新しい欧州(The New Europe)」〔11月19日付)が、なかなか面白い。先ほどまた見たら、ツイート数が1700を超えていた。

ファーガソンは現在ハーバード大学の教授で、何冊も著作がある。よく「気鋭の若手歴史学者」と紹介されている。私も何冊か、著作を持っているのだがーーとても勉強になったものもあれば、??と思うものの個人的にはあったけれどもーー私の印象では保守派ではないかと思う。右か左かというと右という感じ。(左右で分けるのはもう古いと何度かいろいろな人に言われているのだが)。そこをとりあえず踏まえて読んでみたのだが、2021年の欧州像が当たっているのかどうかは別としても、「ありそうな話」なので、一種の知的遊びとしても非常に面白い、ということになる。本当にそうなりそうな感じもしてくる。

ファーガソン氏によれば、

*ユーロはなくならない。生き残る。

*しかし、欧州連合・欧州はいまの形では残らない。

*英国はEUから抜け出て、アイルランドはかつて独立した国、英国と再統合するーーアイルランド人は、ベルギー(いまのEUの本部)よりも、英国のほうがいい、というわけである。英国では国民投票が行われ、僅差でEUからの脱退が決まる。支持を得たキャメロン首相は、今度の総選挙で自分が党首となる保守党の単独政権(2011年現在は、親欧州の自由民主党との連立政権)を成立させる。2021年時点で、キャメロン首相は4期目を務める。

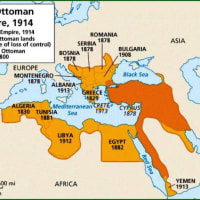

*EUの本部はベルギー・ブリュッセルではなく、オーストリア・ウィーンに移動する(ウィキペディア:ウィーンは第一次世界大戦まではオーストリア=ハンガリー帝国の首都としてドイツを除く中東欧の大部分に君臨し、さらに19世紀後半まではドイツ連邦や神聖ローマ帝国を通じて形式上はドイツ民族全体の帝都でもあった)。

*独立心の強い北欧諸国は、アイスランドを入れて、自分たち自身のまとまり=北部同盟を作る。

*EUはドイツが中心となって、「ユナイテッド・ステーツ・オブ・ヨーロッパ」(欧州合衆国)となる。さらに東欧諸国が入り、2つの言語で割れていたベルギーは原語圏に応じて2つの国となるので、加盟国は29になるという。ウクライナも加盟を望む。英国や北欧諸国は、合衆国を「全ドイツ帝国」と影で呼んでいる。

*合衆国内では、ドイツがある北部と、ギリシャ、イタリア、ポルトガルがある南部には大きな差がある。南部諸国では失業率が20%近くになるが、心配することはない。連邦制だから、北部から資金が流れてくるのだ。

欧州から目を離し、中東や米国はどうなるのだろう?

ファーガソンによれば、

*「中東の春」は長く続かなかった。2012年、イスラエルがイランの核施設を攻撃し、イランはガザ地区やレバノンに攻撃を返す。イスラエルのイランへの攻撃を米国は防げなかった。イランは米国の戦艦をとりおさえ、乗組員全員が人質になる。この大きな失態で、オバマ米大統領の再選への夢は消えたのであるー。

***

この将来像はあくまでも1つの仮説、あるいはお遊びであろうし、ファーガソン氏の政治傾向も考慮して判断しなければならないが、「英国とアイルランドがくっつく」・・・というのがなんとなくありそうで、連日のEU論争を少し長い目で見れそうな気がする。

ファーガソン流に考えれば、決して将来は暗くなく、それぞれの国は引力のようなものによって、落ち着くべきところに落ち着く。外に出たい国は出るし、中にとどまりたい国はとどまるのである。それぞれに違った状況があるのに、「何とかして、全体を守ろう・現状を維持しよう」とするから無理があるのかなと思えてくる。

http://ukmedia.exblog.jp/17194536/

●Niall Ferguson on 2021: The New Europe - WSJ.com

Niall Ferguson peers into Europe's future and sees Greek gardeners, German sunbathers—and a new fiscal union. Welcome to the other United States..

Map illustration by Peter Arkle

'Life is still far from easy in the peripheral states of the United States of Europe (as the euro zone is now known).'

.Welcome to Europe, 2021. Ten years have elapsed since the great crisis of 2010-11, which claimed the scalps of no fewer than 10 governments, including Spain and France. Some things have stayed the same, but a lot has changed.

The euro is still circulating, though banknotes are now seldom seen. (Indeed, the ease of electronic payments now makes some people wonder why creating a single European currency ever seemed worth the effort.) But Brussels has been abandoned as Europe's political headquarters. Vienna has been a great success.

"There is something about the Habsburg legacy," explains the dynamic new Austrian Chancellor Marsha Radetzky. "It just seems to make multinational politics so much more fun."

The U.S. has lost its position as the best place to do business, and China and the rest of the East have so mastered the ways of the West that they're charting a whole new economic paradigm, Harvard historian Niall Ferguson says in an interview with WSJ's John Bussey. Photo courtesy of Jeff Bush.

.The Germans also like the new arrangements. "For some reason, we never felt very welcome in Belgium," recalls German Chancellor Reinhold Siegfried von Gotha-Dämmerung.

Life is still far from easy in the peripheral states of the United States of Europe (as the euro zone is now known). Unemployment in Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain has soared to 20%. But the creation of a new system of fiscal federalism in 2012 has ensured a steady stream of funds from the north European core.

Like East Germans before them, South Europeans have grown accustomed to this trade-off. With a fifth of their region's population over 65 and a fifth unemployed, people have time to enjoy the good things in life. And there are plenty of euros to be made in this gray economy, working as maids or gardeners for the Germans, all of whom now have their second homes in the sunny south.

The U.S.E. has actually gained some members. Lithuania and Latvia stuck to their plan of joining the euro, following the example of their neighbor Estonia. Poland, under the dynamic leadership of former Foreign Minister Radek Sikorski, did the same. These new countries are the poster children of the new Europe, attracting German investment with their flat taxes and relatively low wages.

But other countries have left.

David Cameron—now beginning his fourth term as British prime minister—thanks his lucky stars that, reluctantly yielding to pressure from the Euroskeptics in his own party, he decided to risk a referendum on EU membership. His Liberal Democrat coalition partners committed political suicide by joining Labour's disastrous "Yeah to Europe" campaign.

Egged on by the pugnacious London tabloids, the public voted to leave by a margin of 59% to 41%, and then handed the Tories an absolute majority in the House of Commons. Freed from the red tape of Brussels, England is now the favored destination of Chinese foreign direct investment in Europe. And rich Chinese love their Chelsea apartments, not to mention their splendid Scottish shooting estates.

In some ways this federal Europe would gladden the hearts of the founding fathers of European integration. At its heart is the Franco-German partnership launched by Jean Monnet and Robert Schuman in the 1950s. But the U.S.E. of 2021 is a very different thing from the European Union that fell apart in 2011.

* * *

It was fitting that the disintegration of the EU should be centered on the two great cradles of Western civilization, Athens and Rome. But George Papandreou and Silvio Berlusconi were by no means the first European leaders to fall victim to what might be called the curse of the euro.

Since financial fear had started to spread through the euro zone in June 2010, no fewer than seven other governments had fallen: in the Netherlands, Slovakia, Belgium, Ireland, Finland, Portugal and Slovenia. The fact that nine governments fell in less than 18 months—with another soon to follow—was in itself remarkable.

But not only had the euro become a government-killing machine. It was also fostering a new generation of populist movements, like the Dutch Party for Freedom and the True Finns. Belgium was on the verge of splitting in two. The very structures of European politics were breaking down.

Who would be next? The answer was obvious. After the election of Nov. 20, 2011, the Spanish prime minister, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, stepped down. His defeat was such a foregone conclusion that he had decided the previous April not to bother seeking re-election.

And after him? The next leader in the crosshairs was the French president, Nicolas Sarkozy, who was up for re-election the following April.

The question on everyone's minds back in November 2011 was whether Europe's monetary union—so painstakingly created in the 1990s—was about to collapse. Many pundits thought so. Indeed, New York University's influential Nouriel Roubini argued that not only Greece but also Italy would have to leave—or be kicked out of—the euro zone.

But if that had happened, it is hard to see how the single currency could have survived. The speculators would immediately have turned their attention to the banks in the next weakest link (probably Spain). Meanwhile, the departing countries would have found themselves even worse off than before. Overnight all of their banks and half of their nonfinancial corporations would have been rendered insolvent, with euro-denominated liabilities but drachma or lira assets.

Restoring the old currencies also would have been ruinously expensive at a time of already chronic deficits. New borrowing would have been impossible to finance other than by printing money. These countries would quickly have found themselves in an inflationary tailspin that would have negated any benefits of devaluation.

For all these reasons, I never seriously expected the euro zone to break up. To my mind, it seemed much more likely that the currency would survive—but that the European Union would disintegrate. After all, there was no legal mechanism for a country like Greece to leave the monetary union. But under the Lisbon Treaty's special article 50, a member state could leave the EU. And that is precisely what the British did.

* * *

Britain got lucky. Accidentally, because of a personal feud between Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, the United Kingdom didn't join the euro zone after Labour came to power in 1997. As a result, the U.K. was spared what would have been an economic calamity when the financial crisis struck.

With a fiscal position little better than most of the Mediterranean countries' and a far larger banking system than in any other European economy, Britain with the euro would have been Ireland to the power of eight. Instead, the Bank of England was able to pursue an aggressively expansionary policy. Zero rates, quantitative easing and devaluation greatly mitigated the pain and allowed the "Iron Chancellor" George Osborne to get ahead of the bond markets with pre-emptive austerity. A better advertisement for the benefits of national autonomy would have been hard to devise.

At the beginning of David Cameron's premiership in 2010, there had been fears that the United Kingdom might break up. But the financial crisis put the Scots off independence; small countries had fared abysmally. And in 2013, in a historical twist only a few die-hard Ulster Unionists had dreamt possible, the Republic of Ireland's voters opted to exchange the austerity of the U.S.E. for the prosperity of the U.K. Postsectarian Irishmen celebrated their citizenship in a Reunited Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland with the slogan: "Better Brits Than Brussels."

Another thing no one had anticipated in 2011 was developments in Scandinavia. Inspired by the True Finns in Helsinki, the Swedes and Danes—who had never joined the euro—refused to accept the German proposal for a "transfer union" to bail out Southern Europe. When the energy-rich Norwegians suggested a five-country Norse League, bringing in Iceland, too, the proposal struck a chord.

The new arrangements are not especially popular in Germany, admittedly. But unlike in other countries, from the Netherlands to Hungary, any kind of populist politics continues to be verboten in Germany. The attempt to launch a "True Germans" party (Die wahren Deutschen) fizzled out amid the usual charges of neo-Nazism.

The defeat of Angela Merkel's coalition in 2013 came as no surprise following the German banking crisis of the previous year. Taxpayers were up in arms about Ms. Merkel's decision to bail out Deutsche Bank, despite the fact that Deutsche's loans to the ill-fated European Financial Stability Fund had been made at her government's behest. The German public was simply fed up with bailing out bankers. "Occupy Frankfurt" won.

Yet the opposition Social Democrats essentially pursued the same policies as before, only with more pro-European conviction. It was the SPD that pushed through the treaty revision that created the European Finance Funding Office (fondly referred to in the British press as "EffOff"), effectively a European Treasury Department to be based in Vienna.

It was the SPD that positively welcomed the departure of the awkward Brits and Scandinavians, persuading the remaining 21 countries to join Germany in a new federal United States of Europe under the Treaty of Potsdam in 2014. With the accession of the six remaining former Yugoslav states—Bosnia, Croatia, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia—total membership in the U.S.E. rose to 28, one more than in the precrisis EU. With the separation of Flanders and Wallonia, the total rose to 29.

Crucially, too, it was the SPD that whitewashed the actions of Mario Draghi, the Italian banker who had become president of the European Central Bank in early November 2011. Mr. Draghi went far beyond his mandate in the massive indirect buying of Italian and Spanish bonds that so dramatically ended the bond-market crisis just weeks after he took office. In effect, he turned the ECB into a lender of last resort for governments.

But Mr. Draghi's brand of quantitative easing had the great merit of working. Expanding the ECB balance sheet put a floor under asset prices and restored confidence in the entire European financial system, much as had happened in the U.S. in 2009. As Mr. Draghi said in an interview in December 2011, "The euro could only be saved by printing it."

So the European monetary union did not fall apart, despite the dire predictions of the pundits in late 2011. On the contrary, in 2021 the euro is being used by more countries than before the crisis.

As accession talks begin with Ukraine, German officials talk excitedly about a future Treaty of Yalta, dividing Eastern Europe anew into Russian and European spheres of influence. One source close to Chancellor Gotha-Dämmerung joked last week: "We don't mind the Russians having the pipelines, so long as we get to keep the Black Sea beaches."

***

On reflection, it was perhaps just as well that the euro was saved. A complete disintegration of the euro zone, with all the monetary chaos that it would have entailed, might have had some nasty unintended consequences. It was easy to forget, amid the febrile machinations that ousted Messrs. Papandreou and Berlusconi, that even more dramatic events were unfolding on the other side of the Mediterranean.

.Back then, in 2011, there were still those who believed that North Africa and the Middle East were entering a bright new era of democracy. But from the vantage point of 2021, such optimism seems almost incomprehensible.

The events of 2012 shook not just Europe but the whole world. The Israeli attack on Iran's nuclear facilities threw a lit match into the powder keg of the "Arab Spring." Iran counterattacked through its allies in Gaza and Lebanon.

Having failed to veto the Israeli action, the U.S. once again sat in the back seat, offering minimal assistance and trying vainly to keep the Straits of Hormuz open without firing a shot in anger. (When the entire crew of an American battleship was captured and held hostage by Iran's Revolutionary Guards, President Obama's slim chance of re-election evaporated.)

Turkey seized the moment to take the Iranian side, while at the same time repudiating Atatürk's separation of the Turkish state from Islam. Emboldened by election victory, the Muslim Brotherhood seized the reins of power in Egypt, repudiating its country's peace treaty with Israel. The king of Jordan had little option but to follow suit. The Saudis seethed but could hardly be seen to back Israel, devoutly though they wished to avoid a nuclear Iran.

Israel was entirely isolated. The U.S. was otherwise engaged as President Mitt Romney focused on his Bain Capital-style "restructuring" of the federal government's balance sheet.

It was in the nick of time that the United States of Europe intervened to prevent the scenario that Germans in particular dreaded: a desperate Israeli resort to nuclear arms. Speaking from the U.S.E. Foreign Ministry's handsome new headquarters in the Ringstrasse, the European President Karl von Habsburg explained on Al Jazeera: "First, we were worried about the effect of another oil price hike on our beloved euro. But above all we were afraid of having radioactive fallout on our favorite resorts."

Looking back on the previous 10 years, Mr. von Habsburg—still known to close associates by his royal title of Archduke Karl of Austria—could justly feel proud. Not only had the euro survived. Somehow, just a century after his grandfather's deposition, the Habsburg Empire had reconstituted itself as the United States of Europe.

Small wonder the British and the Scandinavians preferred to call it the Wholly German Empire.

—Mr. Ferguson is a professor of history at Harvard University and the author of "Civilization: The West and the Rest," published this month by Penguin Press.

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970203699404577044172754446162.html

●ヨーロッパの新しいドイツ問題 ―― 指導国なきヨーロッパ経済の苦悩

Why Only Germany Can Fix the Euro

マティアス・マタイス アメリカン大学准教授

マーク・ブリス ブラウン大学教授

フォーリン・アフェアーズ リポート 2011年12月号

20世紀の多くの時期を通じて、「ドイツ問題」がヨーロッパのエリートたちを苦しめてきた。他のヨーロッパ諸国と比べて、ドイツが余りに強靱で、その経済パワーが大きすぎたからだ。こうして、NATOと欧州統合の枠組みのなかにドイツを取り込んでそのパワーを抑えていくことが戦後ヨーロッパの解決策とされた。だが、現在のドイツ問題とはドイツの弱さに派生している。ユーロ危機を引き起こしている要因は多岐にわたるが、実際には一つのルーツを共有している。それは、ドイツがヨーロッパにおける責任ある経済覇権国としての役割を果たさなかったことだ。かつてアメリカの歴史家C・キンドルバーガーは「1933年の世界経済会議ではさまざまな案が出されたが、リーダーシップを発揮できる立場にあった国の指導者が、国内の懸念に配慮するあまり、状況への傍観を決め込んでしまった」と当時の経済覇権国の姿勢を批判したが、これは、現在のドイツにそのままあてはまる。求められているのは、ルールメーカーではなく、指導者としての役目を果たすことだ。

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

小見出し

EUによるクーデター 部分公開

何が問題なのか

ベルリンでキンドルバーガーを読む

五つの公共財

新たなドイツ問題

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

<EUによるクーデター>

「船長と乗組員が、なぜ問題に遭遇しているかの理由をこうも理解せず、しかも、とるべき重要な対策にも気づかずに船を沈没させてしまったケースはこれまでにない」。大恐慌を前にした政策エリートの判断の間違いを(イギリスの歴史家)エリック・ホブスボームはかつてこう批判した。

当時の指導者は規定の公理に従って、予算を均衡させ、関税を引き下げ、金本位制に復帰したが、結局、事態を悪化させただけだった。ヨーロッパのソブリン債務危機の顛末についても、いずれ、これと似たような見方がされることになるかもしれない。

ギリシャ経済、アイルランド経済、ポルトガル経済が相次いで座礁した後、世界がいまや注目しているのは――世界で八番目に大きな経済と三番目に大きな国債市場をもつ――イタリア経済の行方だ。だが、現在の処方箋には不幸にも20世紀初頭の香りがする。

ヨーロッパ各国が緊縮財政をとり、金本位制の類であるユーロを維持することで、成長路線へと復帰することが提言されている。一方、非常に大きな国際的圧力にさらされたギリシャは、国の指導者をゲオルギオス・パパンドレウから、欧州中央銀行(ECB)副総裁を務めたルーカス・パパデモスに代え、イタリアもシルビオ・ベルルスコーニから、欧州委員会委員を務めた「スーパーマリオ」こと、マリオ・モンティに置き換えた。

だが、こうした「EUによるクーデター」にも関わらず、モンティが指導者になった24時間後には、イタリアの長期国債の金利は再び7%を超えていた。

西洋文明の礎を築き、最初に民主主義を経験したギリシャ人とローマ人が、皮肉にも選挙の洗礼を受けていないテクノクラートたちに経済の運営を委ねている。基盤の弱い民主主義プロセスを経た指導者が、外国の債権者の圧力によって強靱な指導者に置きかえられるという1930年代の気配も漂い始めている。

ホブスボームが指摘した通り、前回はうまくいかなかった。

http://www.foreignaffairsj.co.jp/essay/201112/Blyth.htm

【私のコメント】スコットランド出身でハーバード大学教授のニアル・ファーガソンが「2021:新しい欧州」という記事を米ウオール・ストリート・ジャーナル紙に書いている。この記事に書かれた欧州地図は中央に巨大なドイツが存在し、周囲の国家が小さく描かれている。ドイツを封じ込めるために設立されたEUは、ドイツが欧州大陸を支配するための機関に変容しようとしている。ドイツが欧州大陸を支配する時代が来たことをアングロサクソンも認め始めたということだ。

更にEUの本部がブリュッセルからウィーンに移動するという記述も興味深い。ゲルマン系とラテン系の境界線上にあり、しかもゲルマン系と行ってもドイツではなくオランダであるベルギーから、ドイツ系でありかつての神聖ローマ帝国・オーストリア帝国の首都であったウィーンへの移動は、ドイツの欧州覇権確立を意味する。更に、私が常々述べている様に、第二次世界大戦はカトリックのオーストリアが同じくカトリックのバイエルンと組んでヒトラーをドイツの最高指導者として送り込み、旧プロイセン地域を破滅させるドイツの宗教戦争という一面があったことを考えると、このウィーンへのEU本部移転はオーストリアの第二次世界大戦での勝利を意味すると思われる。

米国外交評議会が発行するフォーリンアフェアーズでも、ドイツが欧州の指導国家でないことを問題視する記事がある。20世紀の米国・連合国が正義でドイツと日本が悪という価値観は21世紀には通用しない。米国の世界覇権、国際金融資本の世界支配が崩壊し、ドイツが正義を回復する時代が来たのだ。当然日本も正義を回復することになる。そして、日独を悪として糾弾することを国家設立の指命として建国されたイスラエルと韓国は存立意義を失い、敵対する周辺国によって滅亡させられることだろう。日本政府が従軍慰安婦問題を最近になって煽りたてたのは、韓国に反日政策を維持させ、近未来に日本が正義を回復した時に韓国を確実に滅亡させることが目的であると考えている。

↓↓↓ 一日一回クリックしていただくと更新の励みになります。

スコットランド出身の歴史学者N・ファーガソンが、米ウオール・ストリート・ジャーナル紙に書いた記事「2021:新しい欧州(The New Europe)」〔11月19日付)が、なかなか面白い。先ほどまた見たら、ツイート数が1700を超えていた。

ファーガソンは現在ハーバード大学の教授で、何冊も著作がある。よく「気鋭の若手歴史学者」と紹介されている。私も何冊か、著作を持っているのだがーーとても勉強になったものもあれば、??と思うものの個人的にはあったけれどもーー私の印象では保守派ではないかと思う。右か左かというと右という感じ。(左右で分けるのはもう古いと何度かいろいろな人に言われているのだが)。そこをとりあえず踏まえて読んでみたのだが、2021年の欧州像が当たっているのかどうかは別としても、「ありそうな話」なので、一種の知的遊びとしても非常に面白い、ということになる。本当にそうなりそうな感じもしてくる。

ファーガソン氏によれば、

*ユーロはなくならない。生き残る。

*しかし、欧州連合・欧州はいまの形では残らない。

*英国はEUから抜け出て、アイルランドはかつて独立した国、英国と再統合するーーアイルランド人は、ベルギー(いまのEUの本部)よりも、英国のほうがいい、というわけである。英国では国民投票が行われ、僅差でEUからの脱退が決まる。支持を得たキャメロン首相は、今度の総選挙で自分が党首となる保守党の単独政権(2011年現在は、親欧州の自由民主党との連立政権)を成立させる。2021年時点で、キャメロン首相は4期目を務める。

*EUの本部はベルギー・ブリュッセルではなく、オーストリア・ウィーンに移動する(ウィキペディア:ウィーンは第一次世界大戦まではオーストリア=ハンガリー帝国の首都としてドイツを除く中東欧の大部分に君臨し、さらに19世紀後半まではドイツ連邦や神聖ローマ帝国を通じて形式上はドイツ民族全体の帝都でもあった)。

*独立心の強い北欧諸国は、アイスランドを入れて、自分たち自身のまとまり=北部同盟を作る。

*EUはドイツが中心となって、「ユナイテッド・ステーツ・オブ・ヨーロッパ」(欧州合衆国)となる。さらに東欧諸国が入り、2つの言語で割れていたベルギーは原語圏に応じて2つの国となるので、加盟国は29になるという。ウクライナも加盟を望む。英国や北欧諸国は、合衆国を「全ドイツ帝国」と影で呼んでいる。

*合衆国内では、ドイツがある北部と、ギリシャ、イタリア、ポルトガルがある南部には大きな差がある。南部諸国では失業率が20%近くになるが、心配することはない。連邦制だから、北部から資金が流れてくるのだ。

欧州から目を離し、中東や米国はどうなるのだろう?

ファーガソンによれば、

*「中東の春」は長く続かなかった。2012年、イスラエルがイランの核施設を攻撃し、イランはガザ地区やレバノンに攻撃を返す。イスラエルのイランへの攻撃を米国は防げなかった。イランは米国の戦艦をとりおさえ、乗組員全員が人質になる。この大きな失態で、オバマ米大統領の再選への夢は消えたのであるー。

***

この将来像はあくまでも1つの仮説、あるいはお遊びであろうし、ファーガソン氏の政治傾向も考慮して判断しなければならないが、「英国とアイルランドがくっつく」・・・というのがなんとなくありそうで、連日のEU論争を少し長い目で見れそうな気がする。

ファーガソン流に考えれば、決して将来は暗くなく、それぞれの国は引力のようなものによって、落ち着くべきところに落ち着く。外に出たい国は出るし、中にとどまりたい国はとどまるのである。それぞれに違った状況があるのに、「何とかして、全体を守ろう・現状を維持しよう」とするから無理があるのかなと思えてくる。

http://ukmedia.exblog.jp/17194536/

●Niall Ferguson on 2021: The New Europe - WSJ.com

Niall Ferguson peers into Europe's future and sees Greek gardeners, German sunbathers—and a new fiscal union. Welcome to the other United States..

Map illustration by Peter Arkle

'Life is still far from easy in the peripheral states of the United States of Europe (as the euro zone is now known).'

.Welcome to Europe, 2021. Ten years have elapsed since the great crisis of 2010-11, which claimed the scalps of no fewer than 10 governments, including Spain and France. Some things have stayed the same, but a lot has changed.

The euro is still circulating, though banknotes are now seldom seen. (Indeed, the ease of electronic payments now makes some people wonder why creating a single European currency ever seemed worth the effort.) But Brussels has been abandoned as Europe's political headquarters. Vienna has been a great success.

"There is something about the Habsburg legacy," explains the dynamic new Austrian Chancellor Marsha Radetzky. "It just seems to make multinational politics so much more fun."

The U.S. has lost its position as the best place to do business, and China and the rest of the East have so mastered the ways of the West that they're charting a whole new economic paradigm, Harvard historian Niall Ferguson says in an interview with WSJ's John Bussey. Photo courtesy of Jeff Bush.

.The Germans also like the new arrangements. "For some reason, we never felt very welcome in Belgium," recalls German Chancellor Reinhold Siegfried von Gotha-Dämmerung.

Life is still far from easy in the peripheral states of the United States of Europe (as the euro zone is now known). Unemployment in Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain has soared to 20%. But the creation of a new system of fiscal federalism in 2012 has ensured a steady stream of funds from the north European core.

Like East Germans before them, South Europeans have grown accustomed to this trade-off. With a fifth of their region's population over 65 and a fifth unemployed, people have time to enjoy the good things in life. And there are plenty of euros to be made in this gray economy, working as maids or gardeners for the Germans, all of whom now have their second homes in the sunny south.

The U.S.E. has actually gained some members. Lithuania and Latvia stuck to their plan of joining the euro, following the example of their neighbor Estonia. Poland, under the dynamic leadership of former Foreign Minister Radek Sikorski, did the same. These new countries are the poster children of the new Europe, attracting German investment with their flat taxes and relatively low wages.

But other countries have left.

David Cameron—now beginning his fourth term as British prime minister—thanks his lucky stars that, reluctantly yielding to pressure from the Euroskeptics in his own party, he decided to risk a referendum on EU membership. His Liberal Democrat coalition partners committed political suicide by joining Labour's disastrous "Yeah to Europe" campaign.

Egged on by the pugnacious London tabloids, the public voted to leave by a margin of 59% to 41%, and then handed the Tories an absolute majority in the House of Commons. Freed from the red tape of Brussels, England is now the favored destination of Chinese foreign direct investment in Europe. And rich Chinese love their Chelsea apartments, not to mention their splendid Scottish shooting estates.

In some ways this federal Europe would gladden the hearts of the founding fathers of European integration. At its heart is the Franco-German partnership launched by Jean Monnet and Robert Schuman in the 1950s. But the U.S.E. of 2021 is a very different thing from the European Union that fell apart in 2011.

* * *

It was fitting that the disintegration of the EU should be centered on the two great cradles of Western civilization, Athens and Rome. But George Papandreou and Silvio Berlusconi were by no means the first European leaders to fall victim to what might be called the curse of the euro.

Since financial fear had started to spread through the euro zone in June 2010, no fewer than seven other governments had fallen: in the Netherlands, Slovakia, Belgium, Ireland, Finland, Portugal and Slovenia. The fact that nine governments fell in less than 18 months—with another soon to follow—was in itself remarkable.

But not only had the euro become a government-killing machine. It was also fostering a new generation of populist movements, like the Dutch Party for Freedom and the True Finns. Belgium was on the verge of splitting in two. The very structures of European politics were breaking down.

Who would be next? The answer was obvious. After the election of Nov. 20, 2011, the Spanish prime minister, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, stepped down. His defeat was such a foregone conclusion that he had decided the previous April not to bother seeking re-election.

And after him? The next leader in the crosshairs was the French president, Nicolas Sarkozy, who was up for re-election the following April.

The question on everyone's minds back in November 2011 was whether Europe's monetary union—so painstakingly created in the 1990s—was about to collapse. Many pundits thought so. Indeed, New York University's influential Nouriel Roubini argued that not only Greece but also Italy would have to leave—or be kicked out of—the euro zone.

But if that had happened, it is hard to see how the single currency could have survived. The speculators would immediately have turned their attention to the banks in the next weakest link (probably Spain). Meanwhile, the departing countries would have found themselves even worse off than before. Overnight all of their banks and half of their nonfinancial corporations would have been rendered insolvent, with euro-denominated liabilities but drachma or lira assets.

Restoring the old currencies also would have been ruinously expensive at a time of already chronic deficits. New borrowing would have been impossible to finance other than by printing money. These countries would quickly have found themselves in an inflationary tailspin that would have negated any benefits of devaluation.

For all these reasons, I never seriously expected the euro zone to break up. To my mind, it seemed much more likely that the currency would survive—but that the European Union would disintegrate. After all, there was no legal mechanism for a country like Greece to leave the monetary union. But under the Lisbon Treaty's special article 50, a member state could leave the EU. And that is precisely what the British did.

* * *

Britain got lucky. Accidentally, because of a personal feud between Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, the United Kingdom didn't join the euro zone after Labour came to power in 1997. As a result, the U.K. was spared what would have been an economic calamity when the financial crisis struck.

With a fiscal position little better than most of the Mediterranean countries' and a far larger banking system than in any other European economy, Britain with the euro would have been Ireland to the power of eight. Instead, the Bank of England was able to pursue an aggressively expansionary policy. Zero rates, quantitative easing and devaluation greatly mitigated the pain and allowed the "Iron Chancellor" George Osborne to get ahead of the bond markets with pre-emptive austerity. A better advertisement for the benefits of national autonomy would have been hard to devise.

At the beginning of David Cameron's premiership in 2010, there had been fears that the United Kingdom might break up. But the financial crisis put the Scots off independence; small countries had fared abysmally. And in 2013, in a historical twist only a few die-hard Ulster Unionists had dreamt possible, the Republic of Ireland's voters opted to exchange the austerity of the U.S.E. for the prosperity of the U.K. Postsectarian Irishmen celebrated their citizenship in a Reunited Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland with the slogan: "Better Brits Than Brussels."

Another thing no one had anticipated in 2011 was developments in Scandinavia. Inspired by the True Finns in Helsinki, the Swedes and Danes—who had never joined the euro—refused to accept the German proposal for a "transfer union" to bail out Southern Europe. When the energy-rich Norwegians suggested a five-country Norse League, bringing in Iceland, too, the proposal struck a chord.

The new arrangements are not especially popular in Germany, admittedly. But unlike in other countries, from the Netherlands to Hungary, any kind of populist politics continues to be verboten in Germany. The attempt to launch a "True Germans" party (Die wahren Deutschen) fizzled out amid the usual charges of neo-Nazism.

The defeat of Angela Merkel's coalition in 2013 came as no surprise following the German banking crisis of the previous year. Taxpayers were up in arms about Ms. Merkel's decision to bail out Deutsche Bank, despite the fact that Deutsche's loans to the ill-fated European Financial Stability Fund had been made at her government's behest. The German public was simply fed up with bailing out bankers. "Occupy Frankfurt" won.

Yet the opposition Social Democrats essentially pursued the same policies as before, only with more pro-European conviction. It was the SPD that pushed through the treaty revision that created the European Finance Funding Office (fondly referred to in the British press as "EffOff"), effectively a European Treasury Department to be based in Vienna.

It was the SPD that positively welcomed the departure of the awkward Brits and Scandinavians, persuading the remaining 21 countries to join Germany in a new federal United States of Europe under the Treaty of Potsdam in 2014. With the accession of the six remaining former Yugoslav states—Bosnia, Croatia, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia—total membership in the U.S.E. rose to 28, one more than in the precrisis EU. With the separation of Flanders and Wallonia, the total rose to 29.

Crucially, too, it was the SPD that whitewashed the actions of Mario Draghi, the Italian banker who had become president of the European Central Bank in early November 2011. Mr. Draghi went far beyond his mandate in the massive indirect buying of Italian and Spanish bonds that so dramatically ended the bond-market crisis just weeks after he took office. In effect, he turned the ECB into a lender of last resort for governments.

But Mr. Draghi's brand of quantitative easing had the great merit of working. Expanding the ECB balance sheet put a floor under asset prices and restored confidence in the entire European financial system, much as had happened in the U.S. in 2009. As Mr. Draghi said in an interview in December 2011, "The euro could only be saved by printing it."

So the European monetary union did not fall apart, despite the dire predictions of the pundits in late 2011. On the contrary, in 2021 the euro is being used by more countries than before the crisis.

As accession talks begin with Ukraine, German officials talk excitedly about a future Treaty of Yalta, dividing Eastern Europe anew into Russian and European spheres of influence. One source close to Chancellor Gotha-Dämmerung joked last week: "We don't mind the Russians having the pipelines, so long as we get to keep the Black Sea beaches."

***

On reflection, it was perhaps just as well that the euro was saved. A complete disintegration of the euro zone, with all the monetary chaos that it would have entailed, might have had some nasty unintended consequences. It was easy to forget, amid the febrile machinations that ousted Messrs. Papandreou and Berlusconi, that even more dramatic events were unfolding on the other side of the Mediterranean.

.Back then, in 2011, there were still those who believed that North Africa and the Middle East were entering a bright new era of democracy. But from the vantage point of 2021, such optimism seems almost incomprehensible.

The events of 2012 shook not just Europe but the whole world. The Israeli attack on Iran's nuclear facilities threw a lit match into the powder keg of the "Arab Spring." Iran counterattacked through its allies in Gaza and Lebanon.

Having failed to veto the Israeli action, the U.S. once again sat in the back seat, offering minimal assistance and trying vainly to keep the Straits of Hormuz open without firing a shot in anger. (When the entire crew of an American battleship was captured and held hostage by Iran's Revolutionary Guards, President Obama's slim chance of re-election evaporated.)

Turkey seized the moment to take the Iranian side, while at the same time repudiating Atatürk's separation of the Turkish state from Islam. Emboldened by election victory, the Muslim Brotherhood seized the reins of power in Egypt, repudiating its country's peace treaty with Israel. The king of Jordan had little option but to follow suit. The Saudis seethed but could hardly be seen to back Israel, devoutly though they wished to avoid a nuclear Iran.

Israel was entirely isolated. The U.S. was otherwise engaged as President Mitt Romney focused on his Bain Capital-style "restructuring" of the federal government's balance sheet.

It was in the nick of time that the United States of Europe intervened to prevent the scenario that Germans in particular dreaded: a desperate Israeli resort to nuclear arms. Speaking from the U.S.E. Foreign Ministry's handsome new headquarters in the Ringstrasse, the European President Karl von Habsburg explained on Al Jazeera: "First, we were worried about the effect of another oil price hike on our beloved euro. But above all we were afraid of having radioactive fallout on our favorite resorts."

Looking back on the previous 10 years, Mr. von Habsburg—still known to close associates by his royal title of Archduke Karl of Austria—could justly feel proud. Not only had the euro survived. Somehow, just a century after his grandfather's deposition, the Habsburg Empire had reconstituted itself as the United States of Europe.

Small wonder the British and the Scandinavians preferred to call it the Wholly German Empire.

—Mr. Ferguson is a professor of history at Harvard University and the author of "Civilization: The West and the Rest," published this month by Penguin Press.

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970203699404577044172754446162.html

●ヨーロッパの新しいドイツ問題 ―― 指導国なきヨーロッパ経済の苦悩

Why Only Germany Can Fix the Euro

マティアス・マタイス アメリカン大学准教授

マーク・ブリス ブラウン大学教授

フォーリン・アフェアーズ リポート 2011年12月号

20世紀の多くの時期を通じて、「ドイツ問題」がヨーロッパのエリートたちを苦しめてきた。他のヨーロッパ諸国と比べて、ドイツが余りに強靱で、その経済パワーが大きすぎたからだ。こうして、NATOと欧州統合の枠組みのなかにドイツを取り込んでそのパワーを抑えていくことが戦後ヨーロッパの解決策とされた。だが、現在のドイツ問題とはドイツの弱さに派生している。ユーロ危機を引き起こしている要因は多岐にわたるが、実際には一つのルーツを共有している。それは、ドイツがヨーロッパにおける責任ある経済覇権国としての役割を果たさなかったことだ。かつてアメリカの歴史家C・キンドルバーガーは「1933年の世界経済会議ではさまざまな案が出されたが、リーダーシップを発揮できる立場にあった国の指導者が、国内の懸念に配慮するあまり、状況への傍観を決め込んでしまった」と当時の経済覇権国の姿勢を批判したが、これは、現在のドイツにそのままあてはまる。求められているのは、ルールメーカーではなく、指導者としての役目を果たすことだ。

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

小見出し

EUによるクーデター 部分公開

何が問題なのか

ベルリンでキンドルバーガーを読む

五つの公共財

新たなドイツ問題

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

<EUによるクーデター>

「船長と乗組員が、なぜ問題に遭遇しているかの理由をこうも理解せず、しかも、とるべき重要な対策にも気づかずに船を沈没させてしまったケースはこれまでにない」。大恐慌を前にした政策エリートの判断の間違いを(イギリスの歴史家)エリック・ホブスボームはかつてこう批判した。

当時の指導者は規定の公理に従って、予算を均衡させ、関税を引き下げ、金本位制に復帰したが、結局、事態を悪化させただけだった。ヨーロッパのソブリン債務危機の顛末についても、いずれ、これと似たような見方がされることになるかもしれない。

ギリシャ経済、アイルランド経済、ポルトガル経済が相次いで座礁した後、世界がいまや注目しているのは――世界で八番目に大きな経済と三番目に大きな国債市場をもつ――イタリア経済の行方だ。だが、現在の処方箋には不幸にも20世紀初頭の香りがする。

ヨーロッパ各国が緊縮財政をとり、金本位制の類であるユーロを維持することで、成長路線へと復帰することが提言されている。一方、非常に大きな国際的圧力にさらされたギリシャは、国の指導者をゲオルギオス・パパンドレウから、欧州中央銀行(ECB)副総裁を務めたルーカス・パパデモスに代え、イタリアもシルビオ・ベルルスコーニから、欧州委員会委員を務めた「スーパーマリオ」こと、マリオ・モンティに置き換えた。

だが、こうした「EUによるクーデター」にも関わらず、モンティが指導者になった24時間後には、イタリアの長期国債の金利は再び7%を超えていた。

西洋文明の礎を築き、最初に民主主義を経験したギリシャ人とローマ人が、皮肉にも選挙の洗礼を受けていないテクノクラートたちに経済の運営を委ねている。基盤の弱い民主主義プロセスを経た指導者が、外国の債権者の圧力によって強靱な指導者に置きかえられるという1930年代の気配も漂い始めている。

ホブスボームが指摘した通り、前回はうまくいかなかった。

http://www.foreignaffairsj.co.jp/essay/201112/Blyth.htm

【私のコメント】スコットランド出身でハーバード大学教授のニアル・ファーガソンが「2021:新しい欧州」という記事を米ウオール・ストリート・ジャーナル紙に書いている。この記事に書かれた欧州地図は中央に巨大なドイツが存在し、周囲の国家が小さく描かれている。ドイツを封じ込めるために設立されたEUは、ドイツが欧州大陸を支配するための機関に変容しようとしている。ドイツが欧州大陸を支配する時代が来たことをアングロサクソンも認め始めたということだ。

更にEUの本部がブリュッセルからウィーンに移動するという記述も興味深い。ゲルマン系とラテン系の境界線上にあり、しかもゲルマン系と行ってもドイツではなくオランダであるベルギーから、ドイツ系でありかつての神聖ローマ帝国・オーストリア帝国の首都であったウィーンへの移動は、ドイツの欧州覇権確立を意味する。更に、私が常々述べている様に、第二次世界大戦はカトリックのオーストリアが同じくカトリックのバイエルンと組んでヒトラーをドイツの最高指導者として送り込み、旧プロイセン地域を破滅させるドイツの宗教戦争という一面があったことを考えると、このウィーンへのEU本部移転はオーストリアの第二次世界大戦での勝利を意味すると思われる。

米国外交評議会が発行するフォーリンアフェアーズでも、ドイツが欧州の指導国家でないことを問題視する記事がある。20世紀の米国・連合国が正義でドイツと日本が悪という価値観は21世紀には通用しない。米国の世界覇権、国際金融資本の世界支配が崩壊し、ドイツが正義を回復する時代が来たのだ。当然日本も正義を回復することになる。そして、日独を悪として糾弾することを国家設立の指命として建国されたイスラエルと韓国は存立意義を失い、敵対する周辺国によって滅亡させられることだろう。日本政府が従軍慰安婦問題を最近になって煽りたてたのは、韓国に反日政策を維持させ、近未来に日本が正義を回復した時に韓国を確実に滅亡させることが目的であると考えている。

↓↓↓ 一日一回クリックしていただくと更新の励みになります。

↑

どのコメントも最後はコレ!

だったら、2行で済むだろ!

「ちなみに比較的、人造石油の工業化に成功したドイツの場合は、1937年の時点で日産7.2万バレル、1943年の時点で日産12.4万バレルで、大戦全期間を通じて航空用燃料のほぼすべてを人造石油でまかなっていました。なお、日本の人造石油の生産量ですが、最大の年産量は70万バレル程度であるという資料もあります。」

「それと旧軍の代用石油といえば、松の木の根っこを掘り出して作る松根油(しょうこんゆ)が有名ですが、1945年6月に月産7万バレルを記録した松根油は、精製上の難点は解決されなかったようで結局終戦まで航空機用に使われた形跡はありませんでした。終戦後、アメリカ軍が試験的にジープでその燃料を使ってみると、数日にしてエンジンが止まってジープはスクラップになったそうです。」

ロシアの天然ガスが樺太から北海道経由で日本本土にやってくるかの瀬戸際という事です。それぞれ自分自身の事を優先し、社会や国家を顧みない人間しか存在しないなら、そのような国家や社会は滅亡します。

http://p.tl/y1bD