The Finno-Ugrics The dying fish swims in water Dec 20th 2005 | MARI-EL, RUSSIA, AND TALLINN

Russia finds outside support for its ethnic minorities threatening

IF YOU want to embarrass a Finn, and infuriate a Russian, raise your vodka glass to “Suuri Suomi—Uraliin asti!”. That means “Greater Finland—to the Urals and beyond”. It sounds fanciful, even potty. But it used to be real geopolitics. In the dying days of the Tsarist empire, a swathe of Russia bubbled with nationalist agitation among minorities, many with ethnic ties to Finland.

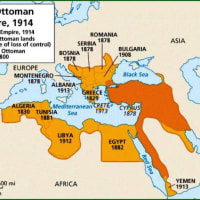

The Finns themselves got away for good. Their ethnic kinsfolk—the Komi, Mari, Udmurts and the like—managed it only briefly. In 1917-18 there was a big country in the middle of Russia called Idel-Ural (literally, “Volga-Ural”) which united the Finno-Ugric (the “Ugric” because of distant cousinship with Hungary) and Turkic peoples in those areas. When it was crushed by the Bolsheviks in late 1918, its refugee foreign minister, Sadrí Maqsudí Arsal, got a warm welcome first in Finland and then Estonia.

In Russian nightmares at least, that spectre now looms again. According to Vladislav Surkov, an adviser to Vladimir Putin, there is a “premeditated system of operations” by Finland, Estonia and the European Union to fan discontent. The more nationalist papers have steamy stories of westerners plotting Russia's destruction. After Mr Putin said recently that foreign-financed groups should be subject to strict scrutiny by the Russian security agencies, a website with close ties to officialdom, news12.ru, said that pro-Mari pressure groups would now be investigated further (the site also accused “Estonian nationalists” of stoking riots in Paris).

Yet the Finno-Ugric axis in world politics seems more like a curiosity than a conspiracy. Although the Finns and Estonians are close (their languages are as similar as Italian and Spanish), ties with Hungary are mainly sentimental. Common linguistic roots are extremely distant. A Finno-Ugric joke tells of migrating tribal forebears finding a signpost on the steppe reading: “To civilisation”. Those that could not read it went north and became Finns. Those that could went to central Europe and became Hungarians. (Finns tell the story the other way round.)

Today the connection looks flimsy. Philologists' labours have identified some 200 words with common roots in all three main Finno-Ugric tongues. Fully 55 of these concern fishing, and a further 15 are about reindeer; only three are about commerce. An Estonian philologist, Mall Hellam, came up with just one mutually comprehensible sentence: “the living fish swims in water.”*

Hungary's involvement in the Finno-Ugric movement is the most low-key. The country's left-of-centre government has good relations with Russia, and no desire to get involved in what it sees as the squabbles of its Russophobic northern cousins. But the hard-pressed Finno-Ugric minorities in central Russian regions like Mari-El, Komi and Udmurtia are more concerned. To them, Estonia, with its regained statehood, is a miracle, and Finland an enviable superpower. For the minority Finno-Ugric languages of Russia are dying, spoken mainly by old people in the countryside and a handful of intellectuals. There are few books, newspapers, radio or TV programmes and little mother-tongue education. It is Russian that signifies culture and civilisation; the local lingo, for many, is useless peasant gobbledegook.

That would have been Estonia's fate too, had the Soviet Union not collapsed in 1991. Estonians were well on the way to becoming a minority in their own country thanks to the migration of Russian-speakers from elsewhere in the empire; the use of Russian in education was growing fast.

For ardent Finno-Ugric activists, Russian linguistic chauvinism is part of something worse. An appeal from the Foundation for the Salvation of the Erzya Language described the position of its people, who mainly live in the central Russian republic of Mordovia, as “critical and even hopeless” because of the Russocentrism of the education system and public broadcasting. “Imperial aggression” had led to a sharp drop in the ethnic population, it said, accusing the local and federal authorities of “genocide”.

Strong stuff—but it is true that many of Russia's 100-odd minority tongues are dying out. Shor, for example, a language in southern Russia with Turkic and Finnic roots, is spoken by only 10,000 people, mainly elderly. A book of poems by Gennady Kostochakov, one of a handful of Shor academic specialists, is entitled “I am the last Shor poet”. Even that is enviable by some standards. The Votian language, a close relative of Estonian, is spoken by just 20 people in a couple of villages in north-western Russia.

Speaking of tongues

Sitting in a Hungarian restaurant in bustling Tallinn, Andres Heinapuu, a top Estonian Finno-Ugrist (who learnt Votian in five days), gives a depressing description of apathetic, hostile or ignorant officialdom in the Russian provinces. Only in Mari-El did the authorities make an effort to create bilingualism in the early post-Soviet years, and now even that has gone into reverse. The republic's rulers have purged ethnic Mari officials and sharply cut Mari-language media and education. Mari activists have suffered beatings, and one suspicious death.

Worse, the Finno-Ugric minorities are not as robust as their Turkic counterparts, Mr Heinapuu says. “The Finno-Ugric character is different—we are used to running away”. Whereas the Turkic minorities' identity in places such as Tatarstan is bolstered by Islam, the Finno-Ugrics' tradition—and sometimes current practice—is pagan. Mari-El and Udmurtia are probably the only places in Europe where shamanism (nature-worship) is still an authentic, organised religion, with weddings celebrated in sacred groves.

So what to do? Barring a collapse of the Russian state, any idea of Estonian-style independence seems hopeless: in every one of the Finno-Ugric bits of Russia, the Indo-Europeans are a majority. In Mordovia, for example, the Erzyas and their ethnic cousins, the Mokshas, together make up less than a third of the population.

So the main task is survival. Mr Heinapuu and his colleagues try to bolster their kinsfolk's language and culture and highlight Russian chauvinism. The first is difficult. In the two-room world headquarters of the Finno-Ugric movement in Tallinn, Mr Heinapuu proudly shows a shelf of newly published poetry in Mari and other languages. It is a drop in the ocean. “What we really need is the ‘Da Vinci Code’ in Udmurt,” a colleague ruefully complains.

A more promising idea is to bring students from the Finno-Ugric bits of Russia to study in Estonia. That initiative, the Kindred Peoples' Programme, began in 1999. It was meant to create expertise, expose students to western society, and boost morale.

It hasn't worked out like that, though. Half the 100-odd students decided to stay. “These were the first towns they had ever lived in. They adapted too well, and those that went back had problems with Russian life,” says Mr Heinapuu. Now the focus has shifted to graduate education. And the money involved in the student programme is tiny: just 3m Estonian kroons ($230,000). Rich Finland gives only a bit more, Hungary almost nothing.

That leaves the one area where the Finno-Ugric movement can claim some success: propaganda initiatives by politicians and activists. In May this year the European Parliament voted to condemn the authorities in Mari-El.

That got the Russian authorities riled. So did an academic conference in August held in the Mari capital, Yoshkar-Ola. The president of Mari-El, a bombastic Kremlin loyalist, Leonid Markelov, was confronted, seemingly for the first time, with the fact that some outsiders—including ambassadors and politicians from the Finno-Ugric countries, plus a bunch of academics—found his rural subjects' odd customs and strange speech rather interesting.

The conference also highlighted the launch of a new Mari-language radio station, which—crucially—will include not just the folk-music and poetry beloved by cultural conservationists, but also modern idioms such as rap music in Mari.

It is possible to reverse language decline. Norway, for example, has poured money into supporting the culture and language of its northern Sami peoples. There is no sign of that in Russia, where the authorities approach minority languages with neglect and suspicion. When Tatarstan, the core of the old Idel-Ural, tried to reintroduce the Latin alphabet in which the local Turkic language is most logically written, this was banned by the Kremlin.

It is hard to match the modest protests by a loose movement consisting mainly of concerned philologists and ethnographers with the allergic reaction they prompt. The Finno-Ugrists' aim is to halt their kinsfolk's extinction, not to break up Russia. Yet viewed through the lens of Russia's uneasy relationship with its imperial history, the hostile reaction is logical. The collapse of the Soviet Union—called a “catastrophe” by Mr Putin—is still echoing today. In most of the former empire, Russian language and culture are still in headlong retreat. In the Caucasus, Azerbaijan has succeeded where Tatarstan failed, in dropping the cyrillic alphabet. In Georgia, English is overtaking Russian as the second language of the elite.

The involvement of Estonia adds extra aggravation. It is much disliked by Russians for its economic success and strongly anti-Soviet take on history, and for encouraging local Russians stranded by the Soviet collapse to learn Estonian and apply for citizenship. To Mr Heinapuu and his pals, the Russian ire they arouse is a backhanded compliment. But it is yet more bad news for the people they are trying to help.

Russia finds outside support for its ethnic minorities threatening

IF YOU want to embarrass a Finn, and infuriate a Russian, raise your vodka glass to “Suuri Suomi—Uraliin asti!”. That means “Greater Finland—to the Urals and beyond”. It sounds fanciful, even potty. But it used to be real geopolitics. In the dying days of the Tsarist empire, a swathe of Russia bubbled with nationalist agitation among minorities, many with ethnic ties to Finland.

The Finns themselves got away for good. Their ethnic kinsfolk—the Komi, Mari, Udmurts and the like—managed it only briefly. In 1917-18 there was a big country in the middle of Russia called Idel-Ural (literally, “Volga-Ural”) which united the Finno-Ugric (the “Ugric” because of distant cousinship with Hungary) and Turkic peoples in those areas. When it was crushed by the Bolsheviks in late 1918, its refugee foreign minister, Sadrí Maqsudí Arsal, got a warm welcome first in Finland and then Estonia.

In Russian nightmares at least, that spectre now looms again. According to Vladislav Surkov, an adviser to Vladimir Putin, there is a “premeditated system of operations” by Finland, Estonia and the European Union to fan discontent. The more nationalist papers have steamy stories of westerners plotting Russia's destruction. After Mr Putin said recently that foreign-financed groups should be subject to strict scrutiny by the Russian security agencies, a website with close ties to officialdom, news12.ru, said that pro-Mari pressure groups would now be investigated further (the site also accused “Estonian nationalists” of stoking riots in Paris).

Yet the Finno-Ugric axis in world politics seems more like a curiosity than a conspiracy. Although the Finns and Estonians are close (their languages are as similar as Italian and Spanish), ties with Hungary are mainly sentimental. Common linguistic roots are extremely distant. A Finno-Ugric joke tells of migrating tribal forebears finding a signpost on the steppe reading: “To civilisation”. Those that could not read it went north and became Finns. Those that could went to central Europe and became Hungarians. (Finns tell the story the other way round.)

Today the connection looks flimsy. Philologists' labours have identified some 200 words with common roots in all three main Finno-Ugric tongues. Fully 55 of these concern fishing, and a further 15 are about reindeer; only three are about commerce. An Estonian philologist, Mall Hellam, came up with just one mutually comprehensible sentence: “the living fish swims in water.”*

Hungary's involvement in the Finno-Ugric movement is the most low-key. The country's left-of-centre government has good relations with Russia, and no desire to get involved in what it sees as the squabbles of its Russophobic northern cousins. But the hard-pressed Finno-Ugric minorities in central Russian regions like Mari-El, Komi and Udmurtia are more concerned. To them, Estonia, with its regained statehood, is a miracle, and Finland an enviable superpower. For the minority Finno-Ugric languages of Russia are dying, spoken mainly by old people in the countryside and a handful of intellectuals. There are few books, newspapers, radio or TV programmes and little mother-tongue education. It is Russian that signifies culture and civilisation; the local lingo, for many, is useless peasant gobbledegook.

That would have been Estonia's fate too, had the Soviet Union not collapsed in 1991. Estonians were well on the way to becoming a minority in their own country thanks to the migration of Russian-speakers from elsewhere in the empire; the use of Russian in education was growing fast.

For ardent Finno-Ugric activists, Russian linguistic chauvinism is part of something worse. An appeal from the Foundation for the Salvation of the Erzya Language described the position of its people, who mainly live in the central Russian republic of Mordovia, as “critical and even hopeless” because of the Russocentrism of the education system and public broadcasting. “Imperial aggression” had led to a sharp drop in the ethnic population, it said, accusing the local and federal authorities of “genocide”.

Strong stuff—but it is true that many of Russia's 100-odd minority tongues are dying out. Shor, for example, a language in southern Russia with Turkic and Finnic roots, is spoken by only 10,000 people, mainly elderly. A book of poems by Gennady Kostochakov, one of a handful of Shor academic specialists, is entitled “I am the last Shor poet”. Even that is enviable by some standards. The Votian language, a close relative of Estonian, is spoken by just 20 people in a couple of villages in north-western Russia.

Speaking of tongues

Sitting in a Hungarian restaurant in bustling Tallinn, Andres Heinapuu, a top Estonian Finno-Ugrist (who learnt Votian in five days), gives a depressing description of apathetic, hostile or ignorant officialdom in the Russian provinces. Only in Mari-El did the authorities make an effort to create bilingualism in the early post-Soviet years, and now even that has gone into reverse. The republic's rulers have purged ethnic Mari officials and sharply cut Mari-language media and education. Mari activists have suffered beatings, and one suspicious death.

Worse, the Finno-Ugric minorities are not as robust as their Turkic counterparts, Mr Heinapuu says. “The Finno-Ugric character is different—we are used to running away”. Whereas the Turkic minorities' identity in places such as Tatarstan is bolstered by Islam, the Finno-Ugrics' tradition—and sometimes current practice—is pagan. Mari-El and Udmurtia are probably the only places in Europe where shamanism (nature-worship) is still an authentic, organised religion, with weddings celebrated in sacred groves.

So what to do? Barring a collapse of the Russian state, any idea of Estonian-style independence seems hopeless: in every one of the Finno-Ugric bits of Russia, the Indo-Europeans are a majority. In Mordovia, for example, the Erzyas and their ethnic cousins, the Mokshas, together make up less than a third of the population.

So the main task is survival. Mr Heinapuu and his colleagues try to bolster their kinsfolk's language and culture and highlight Russian chauvinism. The first is difficult. In the two-room world headquarters of the Finno-Ugric movement in Tallinn, Mr Heinapuu proudly shows a shelf of newly published poetry in Mari and other languages. It is a drop in the ocean. “What we really need is the ‘Da Vinci Code’ in Udmurt,” a colleague ruefully complains.

A more promising idea is to bring students from the Finno-Ugric bits of Russia to study in Estonia. That initiative, the Kindred Peoples' Programme, began in 1999. It was meant to create expertise, expose students to western society, and boost morale.

It hasn't worked out like that, though. Half the 100-odd students decided to stay. “These were the first towns they had ever lived in. They adapted too well, and those that went back had problems with Russian life,” says Mr Heinapuu. Now the focus has shifted to graduate education. And the money involved in the student programme is tiny: just 3m Estonian kroons ($230,000). Rich Finland gives only a bit more, Hungary almost nothing.

That leaves the one area where the Finno-Ugric movement can claim some success: propaganda initiatives by politicians and activists. In May this year the European Parliament voted to condemn the authorities in Mari-El.

That got the Russian authorities riled. So did an academic conference in August held in the Mari capital, Yoshkar-Ola. The president of Mari-El, a bombastic Kremlin loyalist, Leonid Markelov, was confronted, seemingly for the first time, with the fact that some outsiders—including ambassadors and politicians from the Finno-Ugric countries, plus a bunch of academics—found his rural subjects' odd customs and strange speech rather interesting.

The conference also highlighted the launch of a new Mari-language radio station, which—crucially—will include not just the folk-music and poetry beloved by cultural conservationists, but also modern idioms such as rap music in Mari.

It is possible to reverse language decline. Norway, for example, has poured money into supporting the culture and language of its northern Sami peoples. There is no sign of that in Russia, where the authorities approach minority languages with neglect and suspicion. When Tatarstan, the core of the old Idel-Ural, tried to reintroduce the Latin alphabet in which the local Turkic language is most logically written, this was banned by the Kremlin.

It is hard to match the modest protests by a loose movement consisting mainly of concerned philologists and ethnographers with the allergic reaction they prompt. The Finno-Ugrists' aim is to halt their kinsfolk's extinction, not to break up Russia. Yet viewed through the lens of Russia's uneasy relationship with its imperial history, the hostile reaction is logical. The collapse of the Soviet Union—called a “catastrophe” by Mr Putin—is still echoing today. In most of the former empire, Russian language and culture are still in headlong retreat. In the Caucasus, Azerbaijan has succeeded where Tatarstan failed, in dropping the cyrillic alphabet. In Georgia, English is overtaking Russian as the second language of the elite.

The involvement of Estonia adds extra aggravation. It is much disliked by Russians for its economic success and strongly anti-Soviet take on history, and for encouraging local Russians stranded by the Soviet collapse to learn Estonian and apply for citizenship. To Mr Heinapuu and his pals, the Russian ire they arouse is a backhanded compliment. But it is yet more bad news for the people they are trying to help.

※コメント投稿者のブログIDはブログ作成者のみに通知されます