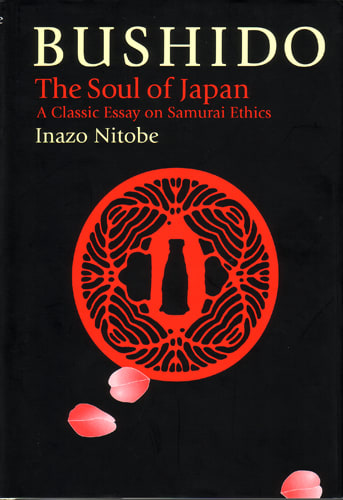

The appeal of the "made in Japan" explanation remains powerful. For much of its modern history, Japan has been categorised as unique and enigmatic. More than 100 years ago, Inazo Nitobe, a Japanese Quaker, attempted to explain the spiritual backbone of the Japanese that had propelled the country's break-neck modernisation, by writing – in English – the highly influential book, Bushido (The Way of the Samurai), which argued for samurai values to be the model for a code of ethics governing the Japanese people. Even HG Wells got into the spirit of things and named the elite class of people in his 1905 novel, A Modern Utopia, the "samurai".・・・

Fast-forward to the post-war economic miracle of Japan in the 1950s and 60s, when the Japanese people became intensely preoccupied with their identity. This led to a flood of pseudo-cultural analysis of why the Japanese people were unique (largely to explain their economic success) – a huge body of popular literature known as the Nihonjinron (discourse on Japaneseness).

It seems only yesterday that Japan Inc ruled the Wall Streets of the world, and all and sundry were trying out Japanese business practices in order to emulate Japanese success. Japanese essentialism has an appeal not only to the Japanese but also to the outside world, because it enables both sides to hide behind the "cultural curtain" and refrain from probing deeper.

さはさりながら、「日本製」という枠組みを用いた説明の訴求力は今でも強力だ。その近代史を通じてほとんど常に日本はユニークかつ謎めいた存在として扱われてきた。例えば、100年以上前のこと、クエーカー教徒の日本人である新渡戸稲造は、この国の近代化に向けた死の跳躍を推進した精神的支柱を説明しようとした。その試みこそ英語で著述され後世に多大の影響を与えた『武士道』(サムライの道)であり、而して、同書は日本国民の行動を律する倫理的規則の原型になり得るものとしてサムライの価値観を称揚した。そして、HG Wellsさえこの武士道に共感してしまい、1905年に上梓した小説、『近代のユートピア』に登場するエリート階級を「サムライ」と名付けるに至る。(中略)

話はひとっ飛びに1950年代と1960年代に、戦後日本の奇跡の経済成長に移る。日本国民が日本人の自己同一性の探求に無我夢中になっていたあの時代である。この時期、日本人はなにゆえにユニークなのかを論じる眉唾ものの文化分析が大量に産み出された(その文化分析はおおよそ日本の経済的成功を説明するものだったのだけれども)。つまり、「日本人論」(日本人の本性と日本人的の属性を巡る議論)と呼ばれる膨大な大衆受けする文献群が産み出されたのだ。

日本株式会社が世界中の金融センターを席捲したのはついこの間のことのように思われる。そして、ついこの間まで、日本の成功にあやかるべく誰もが我も我もと日本的経営のやり方を試そうとしていたのではなかったか。ことほど左様に、日本人ならではの特質、すなわち、ある人が彼や彼女が日本人であるということだけを理由に保持していると想定される日本人の本性なるものを前提とした本質主義は、日本人だけでなく日本以外の世界に対しても説得力を保っている。なぜならば、本質主義的なこの日本人論は、日本人とそれ以外のそれら両者がともに「文化のカーテン」の背後に隠れることを可能にするから、つまり、より踏み込んだ探求の労苦から両者をともに免除してくれるのだから。

Tellingly, there is no mention of the "made in Japan" explanation in the Japanese original of Thursday's report. Instead, it explains the disaster in terms of "regulatory capture" – that is, that the relationship between the regulators and the regulated was much too close, enabling the regulated to subject the regulators to undue pressure and influence. By referring to regulatory capture, the Japanese report points the finger of blame at the complex entanglement of political, bureaucratic, and financial interests dating back to the heyday of high economic growth, a thinly veiled criticism of the one-party Liberal Democratic party rule that has dominated Japan's politico-industrial world for much of the post-1945 era. In the English edition, regulatory capture appears in the main report but not in the chairman's message.

Bringing out the "made in Japan" argument is not helpful. It panders to the uniqueness idea and does not explain, but rather reinforces, existing stereotypes. Moreover, the supposedly Japanese qualities that the report outlines, such as obedience, reluctance to question authority, "sticking with the programme" and insularity, are not at all unique to Japan, but are universal qualities in all societies.

Putting a cultural gloss on the critical investigative report sends a confusing message to the global community – particularly when it comes from a country that is a world leader in technological sophistication.

種明かしをすれば、木曜日【2012年7月5日】に公表された報告書の日本語版の原本には「日本製」という枠組みを用いた説明は皆無なのだ。その代わり、日本語の原本は、この福島原発の災害原因を「規制の虜:regulatory capture」という切り口から究明している。「規制の虜」とは、規制する側と規制される側の関係が親密すぎること、敷衍すれば、規制される側が規制する側を不当な圧力や影響に従わせることが可能なほど両者の関係が親密ということである。規制の虜に言及しつつ報告書の日本語原本は、複雑に絡み合った複合体を糾弾する。すなわち、高度経済成長の最盛期にまで遡る、政界と官界と財界の三者が形成する利権の複合体を批判しているのだ。而して、名指しこそしていないものの【a thinly veiled】、それは1945年以降の戦後のほとんどの時期を通して日本の政財界を牛耳った自民党の一党支配体制に対する批判とも言える。ちなみに、規制の虜という言葉はこの報告書の英語版でもその本編部分には記されているものの、調査委員会の委員長の筆になる序文には登場しない。

蓋し、「日本製の災害」なる議論を持ち出すことは無益である。それは、日本の独自性なるものに興味を懐く向きの歓心を買うにせよ、原因の説明ではない。というか、寧ろ、それは既存の固定概念を補強するものだ。加之、日本人の特性なるものとしてこの報告書がその輪郭を描いた諸性質、すなわち、従順さ、権威者に事を問いただすことに尻込みする態度、「計画が一旦決められた以上、どこまでもその計画に沿って行動したい」という意識、そして、「島国根性」は、まったくもって日本人の専売特許などではなく、あらゆる社会に観察される人間の普遍的な性質なのである。

畢竟、福島原発事故の調査報告書の如き重要な報告書に文化論的なこじつけを持ち込むことは混乱したメッセージを国際社会に発信するものだ。就中、その眉唾ものの文化論が産業技術の洗練性において世界をリードしている国から発信される場合にはなおさらそう言える。

(ガ-ディアン記事の紹介はここまで)

<続く>