●ジャパン・ハンドラーズと国際金融情報 : 中国は「次の世界覇権国」になりうるか?

国際金融資本は、一七世紀のオランダ、一八世紀のイギリス、二〇世紀初頭にアメリカというように世界の覇権を次々に移動させてきた。制度設計をやる係の金融ユダヤ人たちが集団的移動を繰り返すことで、新しい世界の中心を作り出したのである。今度は中国でそういうことをやるのか?ということが私には気になるわけだ。

これは覇権国がその耐用年数として約100年前後で限られているという物理的な問題もある。「フォーリン・ポリシー」の最新号にはロスチャイルド家の公式伝記を書いたイギリスの歴史学者、ニール・ファーガソンが、「世界覇権国には耐用年数が存在する」というような論文を書いていて非常に興味深かった。アメリカの世界覇権からの没落がまともに議論されているという証拠である。

●Empires with Expiration Dates By Niall Ferguson

http://www.allempires.com/forum/forum_posts.asp?TID=14296

http://www.foreignpolicy.com/story/cms.php?story_id=3550

September/October 2006

Empires drive history. But the empires of the past 100 years were short lived, none surviving to see the dawn of the new century. Today, there are no empires, at least not officially. But that could soon change if the United States—or even China—embraces its imperial destiny. How can they avoid the fate of those who came before them?

Empires, more than nation-states, are the principal actors in the history of world events. Much of what we call history consists of the deeds of the 50 to 70 empires that once ruled multiple peoples across large chunks of the globe. Yet, as time has passed, the life span of empires has tended to decline. Compared with their ancient and early modern predecessors, the empires of the last century were remarkably short lived. This phenomenon of reduced imperial life expectancy has profound implications for our own time.

Officially, there are no empires now, only 190-plus nation-states. Yet the ghosts of empires past continue to stalk the Earth. Regional conflicts from Central Africa to the Middle East, and from Central America to the Far East, are easily—and often glibly—explained in terms of earlier imperial sins: an arbitrary border here, a strategy of divide-and-rule there.

Moreover, many of today’s most important states are still recognizably the progeny of empires. Look at the Russian Federation, where less than 80 percent of the population is Russian, or Britain, which is, for all intents and purposes, an English empire. Modern-day Italy and Germany are the products not of nationalism but of Piedmontese and Prussian expansion. Imperial inheritance is even more apparent outside of Europe. India is the heir of the Mughal Empire and, even more manifestly, the British Raj. (An Indian Army officer once told me, “The Indian Army today is more British than the British Army.” Driving with him through the huge barracks at Madras, I saw his point, as hundreds of khaki-clad infantrymen leapt to attention and saluted.) China is the direct descendant of the Middle Kingdom. In the Americas, the imperial legacy is apparent from Canada in the north to Argentina in the south. The Canadian head of state is the British monarch; the Falkland Islands remain a British possession.

Today’s world, in short, is as much a world of ex-empires and ex-colonies as it is a world of nation-states. Even those institutions that were supposed to reorder the world after 1945 have a distinctly imperial bent. For what else are the five permanent members of the U.N. Security Council if not a cozy club of past empires? And what is “humanitarian intervention,” if not a more politically correct-sounding version of the Western empires’ old “civilizing mission”?

Imperial Dating

We tend to assume that the life cycle of empires, great powers, and civilizations has a predictable regularity to it. Yet the most striking thing about past empires is the extraordinary variability in the chronological as well as geographic expanse of their dominion. Especially striking is the fact that the most modern empires have a far shorter life span than their ancient and early modern predecessors.

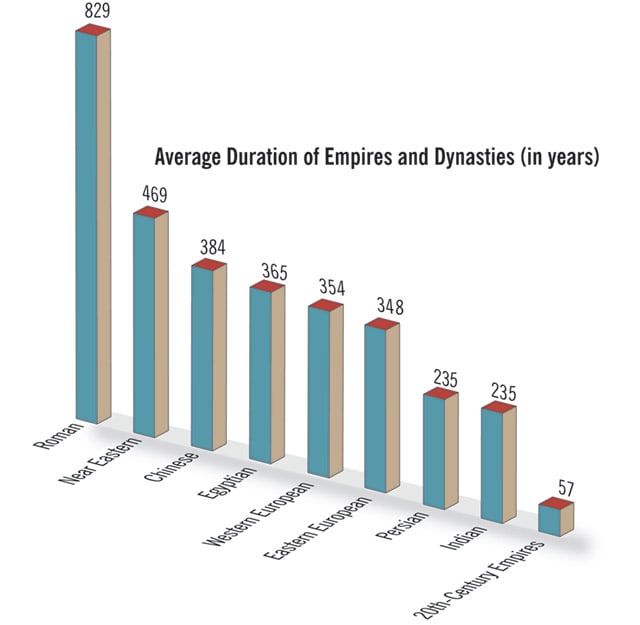

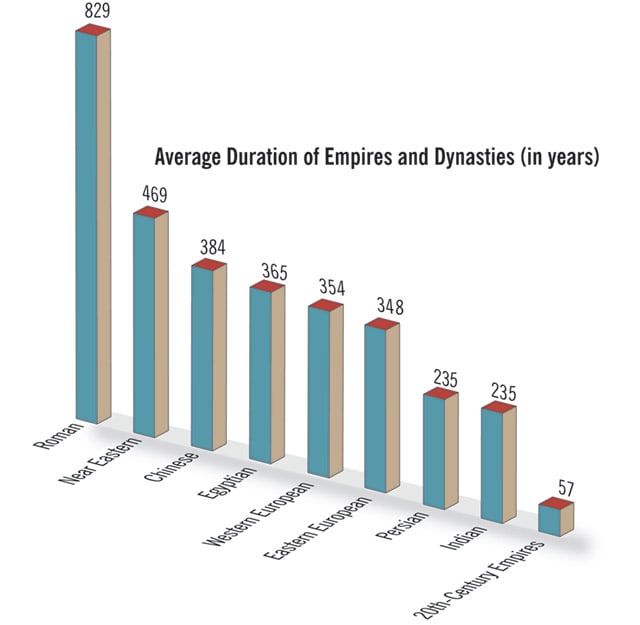

Take the Roman case. The Roman Empire in the West can be dated from 27 B.C., when Octavian became Caesar Augustus and emperor in all but name. It ended when Constantinople was established as a rival capital with the death of the Emperor Theodosius in 395, making a total of 422 years. The Roman Empire in the East can be dated from then until, at the latest, the sack of Byzantium by the Ottoman Turks in 1453, a total of 1,058 years. The Holy Roman Empire—the successor to the Western empire—lasted from 800, when Charlemagne was crowned emperor of the Romans, until Napoleon ended it in 1806. The “average” Roman empire therefore lasted 829 years.

Such calculations, though crude, allow us to compare the life spans of different empires. The three Roman empires were uncharacteristically long lived. By comparison, the average Near Eastern empire (including the Assyrian, Abassid, and Ottoman) lasted a little more than 400 years; the average Egyptian and East European empires around 350 years; the average Chinese empire (subdividing by the principal dynasties) ruled for more than three centuries. The various Indian, Persian, and West European empires generally survived for between 200 and 300 years.

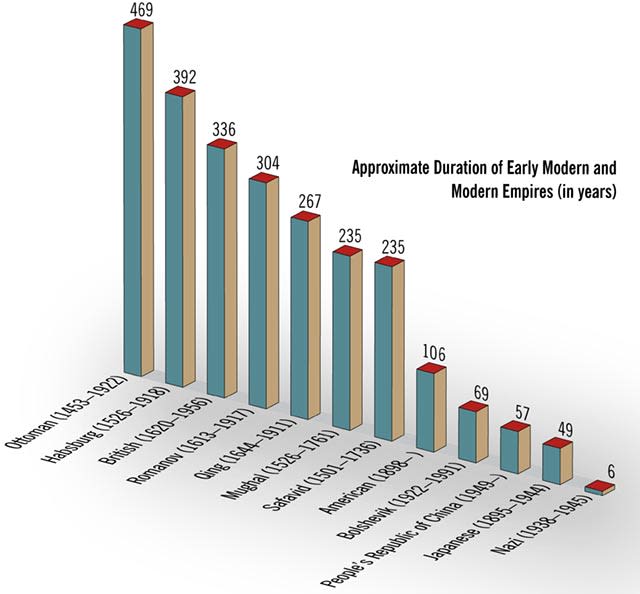

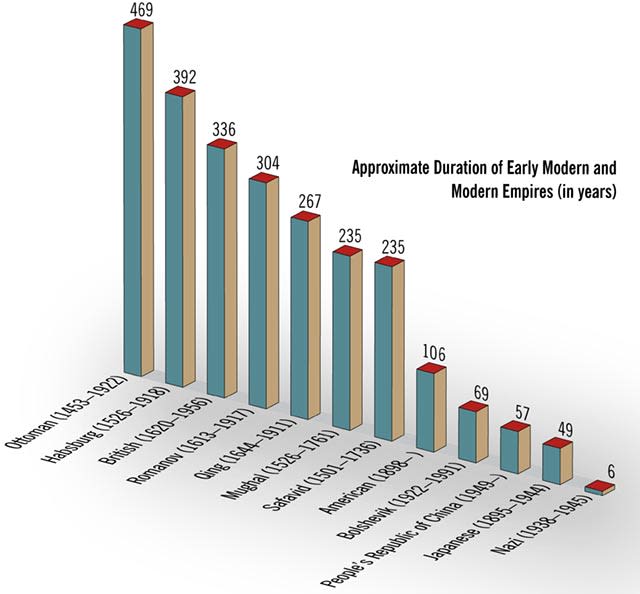

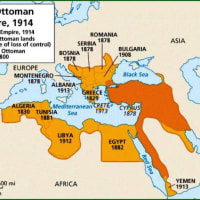

After the sack of Constantinople, the longest-lived empire was clearly the Ottoman at 469 years. The East European empires of the Habsburgs and the Romanovs each existed for more than three centuries. The Mughals ruled a substantial part of what is now India for 235 years. Of an almost identical duration was the reign of the Safavids in Persia.

It is trickier to give precise dates to the maritime empires of the West European states, because these had multiple points of origin and duration. But the British, Dutch, French, and Spanish empires can all be said to have endured for roughly 300 years. The life span of the Portuguese empire was closer to 500.

The empires created in the 20th century, by contrast, were comparatively short. The Bolsheviks’ Soviet Union (1922–91) lasted less than 70 years, a meager record indeed, though one not yet equaled by the People’s Republic of China. Japan’s colonial empire, which can be dated from the acquisition of Taiwan in 1895, lasted barely 50 years. Most fleeting of all modern empires was Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich, which did not extend beyond its predecessor’s borders before 1938 and had retreated within them by early 1945. Technically, the Third Reich lasted 12 years; as an empire in the true sense of the word, exerting power over foreign peoples, it lasted barely half that time. Only Benito Mussolini was a less effective imperialist than Hitler.

Why did the new empires of the 20th century prove so ephemeral? The answer lies partly in the unprecedented degrees of centralized power, economic control, and social homogeneity to which they aspired.

The new empires that arose in the wake of the First World War were not content with the successful but haphazard administrative arrangements that had characterized the old empires, including the messy mixtures of imperial and local law and the delegation of powers and status to certain indigenous groups. They inherited from the 19th-century nation-builders an insatiable appetite for uniformity; these were more like “empire states” than traditional empires. The new empires repudiated traditional religious and legal constraints on the use of force. They insisted on the creation of new hierarchies in place of existing social structures. They delighted in sweeping away old political institutions. Above all, they made a virtue of ruthlessness. In pursuit of their objectives, they were willing to make war on whole categories of people, at home and abroad, rather than merely the armed and trained representatives of an identified enemy state. It was entirely typical of the new generation of would-be emperors that Hitler accused the British of excessive softness in their treatment of Indian nationalists.

The empire states of the mid-20th century were to a considerable extent the architects of their own downfalls. In particular, the Germans and Japanese imposed their authority on other peoples with such ferocity that they undermined local collaboration and laid the foundations for indigenous resistance. That was foolish, as many people who were “liberated” from their old rulers (Stalin in Eastern Europe, the European empires in Asia) by the Axis powers initially welcomed their new masters. At the same time, the territorial ambitions of these empire states were so limitless—and their combined grand strategy so unrealistic—that they swiftly called into being an unbeatable coalition of imperial rivals in the form of the British Empire, the Soviet Union, and the United States.

Page 2

国際金融資本は、一七世紀のオランダ、一八世紀のイギリス、二〇世紀初頭にアメリカというように世界の覇権を次々に移動させてきた。制度設計をやる係の金融ユダヤ人たちが集団的移動を繰り返すことで、新しい世界の中心を作り出したのである。今度は中国でそういうことをやるのか?ということが私には気になるわけだ。

これは覇権国がその耐用年数として約100年前後で限られているという物理的な問題もある。「フォーリン・ポリシー」の最新号にはロスチャイルド家の公式伝記を書いたイギリスの歴史学者、ニール・ファーガソンが、「世界覇権国には耐用年数が存在する」というような論文を書いていて非常に興味深かった。アメリカの世界覇権からの没落がまともに議論されているという証拠である。

●Empires with Expiration Dates By Niall Ferguson

http://www.allempires.com/forum/forum_posts.asp?TID=14296

http://www.foreignpolicy.com/story/cms.php?story_id=3550

September/October 2006

Empires drive history. But the empires of the past 100 years were short lived, none surviving to see the dawn of the new century. Today, there are no empires, at least not officially. But that could soon change if the United States—or even China—embraces its imperial destiny. How can they avoid the fate of those who came before them?

Empires, more than nation-states, are the principal actors in the history of world events. Much of what we call history consists of the deeds of the 50 to 70 empires that once ruled multiple peoples across large chunks of the globe. Yet, as time has passed, the life span of empires has tended to decline. Compared with their ancient and early modern predecessors, the empires of the last century were remarkably short lived. This phenomenon of reduced imperial life expectancy has profound implications for our own time.

Officially, there are no empires now, only 190-plus nation-states. Yet the ghosts of empires past continue to stalk the Earth. Regional conflicts from Central Africa to the Middle East, and from Central America to the Far East, are easily—and often glibly—explained in terms of earlier imperial sins: an arbitrary border here, a strategy of divide-and-rule there.

Moreover, many of today’s most important states are still recognizably the progeny of empires. Look at the Russian Federation, where less than 80 percent of the population is Russian, or Britain, which is, for all intents and purposes, an English empire. Modern-day Italy and Germany are the products not of nationalism but of Piedmontese and Prussian expansion. Imperial inheritance is even more apparent outside of Europe. India is the heir of the Mughal Empire and, even more manifestly, the British Raj. (An Indian Army officer once told me, “The Indian Army today is more British than the British Army.” Driving with him through the huge barracks at Madras, I saw his point, as hundreds of khaki-clad infantrymen leapt to attention and saluted.) China is the direct descendant of the Middle Kingdom. In the Americas, the imperial legacy is apparent from Canada in the north to Argentina in the south. The Canadian head of state is the British monarch; the Falkland Islands remain a British possession.

Today’s world, in short, is as much a world of ex-empires and ex-colonies as it is a world of nation-states. Even those institutions that were supposed to reorder the world after 1945 have a distinctly imperial bent. For what else are the five permanent members of the U.N. Security Council if not a cozy club of past empires? And what is “humanitarian intervention,” if not a more politically correct-sounding version of the Western empires’ old “civilizing mission”?

Imperial Dating

We tend to assume that the life cycle of empires, great powers, and civilizations has a predictable regularity to it. Yet the most striking thing about past empires is the extraordinary variability in the chronological as well as geographic expanse of their dominion. Especially striking is the fact that the most modern empires have a far shorter life span than their ancient and early modern predecessors.

Take the Roman case. The Roman Empire in the West can be dated from 27 B.C., when Octavian became Caesar Augustus and emperor in all but name. It ended when Constantinople was established as a rival capital with the death of the Emperor Theodosius in 395, making a total of 422 years. The Roman Empire in the East can be dated from then until, at the latest, the sack of Byzantium by the Ottoman Turks in 1453, a total of 1,058 years. The Holy Roman Empire—the successor to the Western empire—lasted from 800, when Charlemagne was crowned emperor of the Romans, until Napoleon ended it in 1806. The “average” Roman empire therefore lasted 829 years.

Such calculations, though crude, allow us to compare the life spans of different empires. The three Roman empires were uncharacteristically long lived. By comparison, the average Near Eastern empire (including the Assyrian, Abassid, and Ottoman) lasted a little more than 400 years; the average Egyptian and East European empires around 350 years; the average Chinese empire (subdividing by the principal dynasties) ruled for more than three centuries. The various Indian, Persian, and West European empires generally survived for between 200 and 300 years.

After the sack of Constantinople, the longest-lived empire was clearly the Ottoman at 469 years. The East European empires of the Habsburgs and the Romanovs each existed for more than three centuries. The Mughals ruled a substantial part of what is now India for 235 years. Of an almost identical duration was the reign of the Safavids in Persia.

It is trickier to give precise dates to the maritime empires of the West European states, because these had multiple points of origin and duration. But the British, Dutch, French, and Spanish empires can all be said to have endured for roughly 300 years. The life span of the Portuguese empire was closer to 500.

The empires created in the 20th century, by contrast, were comparatively short. The Bolsheviks’ Soviet Union (1922–91) lasted less than 70 years, a meager record indeed, though one not yet equaled by the People’s Republic of China. Japan’s colonial empire, which can be dated from the acquisition of Taiwan in 1895, lasted barely 50 years. Most fleeting of all modern empires was Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich, which did not extend beyond its predecessor’s borders before 1938 and had retreated within them by early 1945. Technically, the Third Reich lasted 12 years; as an empire in the true sense of the word, exerting power over foreign peoples, it lasted barely half that time. Only Benito Mussolini was a less effective imperialist than Hitler.

Why did the new empires of the 20th century prove so ephemeral? The answer lies partly in the unprecedented degrees of centralized power, economic control, and social homogeneity to which they aspired.

The new empires that arose in the wake of the First World War were not content with the successful but haphazard administrative arrangements that had characterized the old empires, including the messy mixtures of imperial and local law and the delegation of powers and status to certain indigenous groups. They inherited from the 19th-century nation-builders an insatiable appetite for uniformity; these were more like “empire states” than traditional empires. The new empires repudiated traditional religious and legal constraints on the use of force. They insisted on the creation of new hierarchies in place of existing social structures. They delighted in sweeping away old political institutions. Above all, they made a virtue of ruthlessness. In pursuit of their objectives, they were willing to make war on whole categories of people, at home and abroad, rather than merely the armed and trained representatives of an identified enemy state. It was entirely typical of the new generation of would-be emperors that Hitler accused the British of excessive softness in their treatment of Indian nationalists.

The empire states of the mid-20th century were to a considerable extent the architects of their own downfalls. In particular, the Germans and Japanese imposed their authority on other peoples with such ferocity that they undermined local collaboration and laid the foundations for indigenous resistance. That was foolish, as many people who were “liberated” from their old rulers (Stalin in Eastern Europe, the European empires in Asia) by the Axis powers initially welcomed their new masters. At the same time, the territorial ambitions of these empire states were so limitless—and their combined grand strategy so unrealistic—that they swiftly called into being an unbeatable coalition of imperial rivals in the form of the British Empire, the Soviet Union, and the United States.

Page 2

※コメント投稿者のブログIDはブログ作成者のみに通知されます