Page 1

Why We Fight

Empires do not survive for long if they cannot establish and sustain local consent and if they allow more powerful coalitions of rival empires to unite against them. The crucial question is whether or not today’s global powers behave in a different way than their imperial forebears.

Publicly, the leaders of the American and Chinese republics deny that they harbor imperial designs. Both states are the product of revolutions and have long traditions of anti-imperialism. Yet there are moments when the mask slips. U.S. Vice President Dick Cheney’s 2003 Christmas card asked, “And if a sparrow cannot fall to the ground without His notice, is it probable that an empire can rise without His aid?” In 2004 a senior advisor to President Bush confided to journalist Ron Suskind, “We’re an empire now and when we act, we create our own reality.… We’re history’s actors.” Similar thoughts may cross the minds of China’s leaders. Even if they do not, it is still perfectly possible for a republic to behave like an empire in practice, while remaining in denial about its loss of republican virtue.

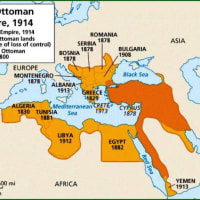

The American empire is young by historical standards. Its continental expansion in the 19th century was unabashedly imperialistic. Yet the comparative ease with which sparsely settled territory was absorbed into the original federal structure militated against the development of an authentically imperial mentality and put minimal strain on the political institutions of the republic. By contrast, America’s era of overseas expansion, which can be marked from the Spanish-American War of 1898, has been a good deal more difficult and, precisely for this reason, has repeatedly conjured up the specter of an imperial presidency. Leaving aside American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, which remain American dependencies, U.S. interventions abroad have typically been brief.

During the course of the 20th century, the United States occupied Panama for 74 years, the Philippines for 48, Palau for 47, Micronesia and the Marshall Islands for 39, Haiti for 19, and the Dominican Republic for 8. The formal postwar occupations of West Germany and Japan continued for, respectively, 10 and 7 years, though U.S. forces still remain in those countries, as well as in South Korea. Troops were also deployed in large numbers in South Vietnam from 1965, though by 1973 they were gone.

This pattern supports the widespread assumption that the U.S. military presence in Afghanistan and Iraq will not last far beyond President George W. Bush’s term in office. Empire—especially unstated empire—is ephemeral in a way that makes our own age quite distinct from previous ages.

In the American case, however, the principal cause of its ephemeral empire is not the alienation of conquered peoples or the threat posed by rival empires (the principal solvents of other 20th-century empires) but domestic constraints. These take three distinct forms. The first can be characterized as a troop deficit. In 1920, when it successfully quelled a major Iraqi insurgency, Britain had one soldier in Iraq for every 23 locals. Today, the United States has just one soldier for every 210 Iraqis.

The problem is not strictly demographic, as is sometimes assumed. For the United States is not short of young people. (It has many times more males aged 15 to 24 than Iraq or Afghanistan.) It is just that the United States prefers to maintain a relatively small proportion of its population in the armed forces, at 0.5 percent. Moreover, only a small and highly trained part of this military is available for combat duties overseas.

Members of this elite group are not easy to sacrifice. Nor are they easy to replace. Each time the newspaper reports the tragedy of another death in action, I am reminded of the lines of Rudyard Kipling, the greatest of the British imperial poets:

A scrimmage in a Border Station

A canter down some dark defile

Two thousand pounds of education

Drops to a ten-rupee jezail

The Crammer’s boast, the Squadron’s pride,

Shot like a rabbit in a ride!

The second constraint on America’s unstated empire is the U.S. budget deficit. The costs of the war in Iraq are proving significantly higher than the administration forecast: $290 billion since the invasion in 2003. That figure is not much in relation to the size of the U.S. economy—less than 2.5 percent of gross domestic product—but it has clearly proved insufficient to achieve the swift postwar reconstruction that might have averted today’s incipient civil war. Other spending priorities, such as the ballooning unfunded liabilities of the Medicare system, have precluded the Marshall Plan for the Middle East that some Iraqis had hoped for.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, there is the American attention deficit. Past empires had little difficulty in sustaining public support for protracted conflicts. The United States, by contrast, has become markedly worse at this. It took less than 18 months for a majority of American voters to start telling pollsters at Gallup that they regarded the invasion of Iraq as a mistake. Comparable levels of disillusionment with the Vietnam War did not set in until August 1968, three years after U.S. forces had arrived en masse, by which time the total number of Americans killed in action was approaching 30,000.

All kinds of pat theories exist to explain the diminished durability of empires in our time. Some say that the reach of the 24-hour news media makes it too hard for would-be imperialists to conceal abuses of power. Others insist that military technology has ceased to confer an unassailable advantage on the United States; improvised explosive devices are the ten-rupee jezails of our time, negating at a stroke the superiority of American weaponry by rendering most of it superfluous.

Yet the real reasons why today’s empires are both ephemeral and undeclared lie elsewhere. Whether we acknowledge them or not, empires repeatedly emerge as history’s actors because of the economies of scale that they make possible. There is a demographic limit to the number of people most nation-states can put under arms. An empire, however, is far less constrained; among its core functions are to mobilize and equip large military forces recruited from multiple peoples and to levy the taxes or raise the loans to pay for them, again drawing on the resources of more than one nationality.

But why fight wars? Again, the answer must be economic. The self-interested objectives of imperial expansion range from the fundamental need to ensure the security of the metropolis by defeating enemies beyond its borders, to the collection of rents and taxation from subject peoples—to say nothing of the more obvious prizes of new land for settlement, raw materials, and treasure. As a general rule, an empire needs to procure these things at lower prices than they would cost in free exchange with independent peoples or with another empire if the costs of conquest and colonization are to be justified.

At the same time, however, an empire may provide “public goods”—that is, benefits of imperial rule that flow not only to the rulers but also to the ruled and, indeed, to third parties. These can include peace in the sense of a Pax Romana, increased trade or investment, improved justice or governance, better education (which may or may not be associated with religious conversion), or improved material conditions.

Imperial rule is not just about boots on the ground. Not only soldiers but also civil servants, settlers, voluntary associations, firms, and local elites can all, in their different ways, serve to impose the will of the center on the periphery. Nor must the benefits of empire flow exclusively to the empire’s rulers and their clients. Colonists drawn from lower income groups in the metropolis may also share in the fruits of empire. Those who stay at home may derive emotional gratification from the victories of distant legions. Local elites may also figure among the winners.

An empire, then, will come into existence and endure so long as the benefits of exerting power over foreign peoples exceed the costs of doing so in the eyes of the imperialists; and so long as the benefits of accepting dominance by a foreign people exceed the costs of resistance in the eyes of the subjects. Such calculations implicitly take into account the potential costs of relinquishing power to another empire.

At the moment, in these terms, the costs of running countries like Iraq and Afghanistan look too high to most Americans; the benefits of doing so seem at best nebulous; and no rival empire seems able or willing to do a better job. With its republican institutions battered but still intact, the United States does not have the air of a new Rome. Although the current president has striven to empower the executive, he is no Octavian.

But all these things could change. In our ever more populous world, where certain natural resources are destined to become more scarce, the old mainsprings of imperial rivalry remain. Look only at China’s recent vigorous pursuit of privileged relationships with major commodity producers in Africa and elsewhere. Or ask how long a neoisolationist America would remain disengaged from the Muslim world in the face of new Islamist terrorist attacks.

Empire today, it is true, is both unstated and unwanted. But history suggests that the calculus of power could swing back in its favor tomorrow.

<END>

Niall Ferguson is Laurence A. Tisch professor of history at Harvard University and senior fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. His latest book is The War of the World: Twentieth Century Conflict and the Descent of the West (New York: Penguin Press, 2006).

Why We Fight

Empires do not survive for long if they cannot establish and sustain local consent and if they allow more powerful coalitions of rival empires to unite against them. The crucial question is whether or not today’s global powers behave in a different way than their imperial forebears.

Publicly, the leaders of the American and Chinese republics deny that they harbor imperial designs. Both states are the product of revolutions and have long traditions of anti-imperialism. Yet there are moments when the mask slips. U.S. Vice President Dick Cheney’s 2003 Christmas card asked, “And if a sparrow cannot fall to the ground without His notice, is it probable that an empire can rise without His aid?” In 2004 a senior advisor to President Bush confided to journalist Ron Suskind, “We’re an empire now and when we act, we create our own reality.… We’re history’s actors.” Similar thoughts may cross the minds of China’s leaders. Even if they do not, it is still perfectly possible for a republic to behave like an empire in practice, while remaining in denial about its loss of republican virtue.

The American empire is young by historical standards. Its continental expansion in the 19th century was unabashedly imperialistic. Yet the comparative ease with which sparsely settled territory was absorbed into the original federal structure militated against the development of an authentically imperial mentality and put minimal strain on the political institutions of the republic. By contrast, America’s era of overseas expansion, which can be marked from the Spanish-American War of 1898, has been a good deal more difficult and, precisely for this reason, has repeatedly conjured up the specter of an imperial presidency. Leaving aside American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, which remain American dependencies, U.S. interventions abroad have typically been brief.

During the course of the 20th century, the United States occupied Panama for 74 years, the Philippines for 48, Palau for 47, Micronesia and the Marshall Islands for 39, Haiti for 19, and the Dominican Republic for 8. The formal postwar occupations of West Germany and Japan continued for, respectively, 10 and 7 years, though U.S. forces still remain in those countries, as well as in South Korea. Troops were also deployed in large numbers in South Vietnam from 1965, though by 1973 they were gone.

This pattern supports the widespread assumption that the U.S. military presence in Afghanistan and Iraq will not last far beyond President George W. Bush’s term in office. Empire—especially unstated empire—is ephemeral in a way that makes our own age quite distinct from previous ages.

In the American case, however, the principal cause of its ephemeral empire is not the alienation of conquered peoples or the threat posed by rival empires (the principal solvents of other 20th-century empires) but domestic constraints. These take three distinct forms. The first can be characterized as a troop deficit. In 1920, when it successfully quelled a major Iraqi insurgency, Britain had one soldier in Iraq for every 23 locals. Today, the United States has just one soldier for every 210 Iraqis.

The problem is not strictly demographic, as is sometimes assumed. For the United States is not short of young people. (It has many times more males aged 15 to 24 than Iraq or Afghanistan.) It is just that the United States prefers to maintain a relatively small proportion of its population in the armed forces, at 0.5 percent. Moreover, only a small and highly trained part of this military is available for combat duties overseas.

Members of this elite group are not easy to sacrifice. Nor are they easy to replace. Each time the newspaper reports the tragedy of another death in action, I am reminded of the lines of Rudyard Kipling, the greatest of the British imperial poets:

A scrimmage in a Border Station

A canter down some dark defile

Two thousand pounds of education

Drops to a ten-rupee jezail

The Crammer’s boast, the Squadron’s pride,

Shot like a rabbit in a ride!

The second constraint on America’s unstated empire is the U.S. budget deficit. The costs of the war in Iraq are proving significantly higher than the administration forecast: $290 billion since the invasion in 2003. That figure is not much in relation to the size of the U.S. economy—less than 2.5 percent of gross domestic product—but it has clearly proved insufficient to achieve the swift postwar reconstruction that might have averted today’s incipient civil war. Other spending priorities, such as the ballooning unfunded liabilities of the Medicare system, have precluded the Marshall Plan for the Middle East that some Iraqis had hoped for.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, there is the American attention deficit. Past empires had little difficulty in sustaining public support for protracted conflicts. The United States, by contrast, has become markedly worse at this. It took less than 18 months for a majority of American voters to start telling pollsters at Gallup that they regarded the invasion of Iraq as a mistake. Comparable levels of disillusionment with the Vietnam War did not set in until August 1968, three years after U.S. forces had arrived en masse, by which time the total number of Americans killed in action was approaching 30,000.

All kinds of pat theories exist to explain the diminished durability of empires in our time. Some say that the reach of the 24-hour news media makes it too hard for would-be imperialists to conceal abuses of power. Others insist that military technology has ceased to confer an unassailable advantage on the United States; improvised explosive devices are the ten-rupee jezails of our time, negating at a stroke the superiority of American weaponry by rendering most of it superfluous.

Yet the real reasons why today’s empires are both ephemeral and undeclared lie elsewhere. Whether we acknowledge them or not, empires repeatedly emerge as history’s actors because of the economies of scale that they make possible. There is a demographic limit to the number of people most nation-states can put under arms. An empire, however, is far less constrained; among its core functions are to mobilize and equip large military forces recruited from multiple peoples and to levy the taxes or raise the loans to pay for them, again drawing on the resources of more than one nationality.

But why fight wars? Again, the answer must be economic. The self-interested objectives of imperial expansion range from the fundamental need to ensure the security of the metropolis by defeating enemies beyond its borders, to the collection of rents and taxation from subject peoples—to say nothing of the more obvious prizes of new land for settlement, raw materials, and treasure. As a general rule, an empire needs to procure these things at lower prices than they would cost in free exchange with independent peoples or with another empire if the costs of conquest and colonization are to be justified.

At the same time, however, an empire may provide “public goods”—that is, benefits of imperial rule that flow not only to the rulers but also to the ruled and, indeed, to third parties. These can include peace in the sense of a Pax Romana, increased trade or investment, improved justice or governance, better education (which may or may not be associated with religious conversion), or improved material conditions.

Imperial rule is not just about boots on the ground. Not only soldiers but also civil servants, settlers, voluntary associations, firms, and local elites can all, in their different ways, serve to impose the will of the center on the periphery. Nor must the benefits of empire flow exclusively to the empire’s rulers and their clients. Colonists drawn from lower income groups in the metropolis may also share in the fruits of empire. Those who stay at home may derive emotional gratification from the victories of distant legions. Local elites may also figure among the winners.

An empire, then, will come into existence and endure so long as the benefits of exerting power over foreign peoples exceed the costs of doing so in the eyes of the imperialists; and so long as the benefits of accepting dominance by a foreign people exceed the costs of resistance in the eyes of the subjects. Such calculations implicitly take into account the potential costs of relinquishing power to another empire.

At the moment, in these terms, the costs of running countries like Iraq and Afghanistan look too high to most Americans; the benefits of doing so seem at best nebulous; and no rival empire seems able or willing to do a better job. With its republican institutions battered but still intact, the United States does not have the air of a new Rome. Although the current president has striven to empower the executive, he is no Octavian.

But all these things could change. In our ever more populous world, where certain natural resources are destined to become more scarce, the old mainsprings of imperial rivalry remain. Look only at China’s recent vigorous pursuit of privileged relationships with major commodity producers in Africa and elsewhere. Or ask how long a neoisolationist America would remain disengaged from the Muslim world in the face of new Islamist terrorist attacks.

Empire today, it is true, is both unstated and unwanted. But history suggests that the calculus of power could swing back in its favor tomorrow.

<END>

Niall Ferguson is Laurence A. Tisch professor of history at Harvard University and senior fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. His latest book is The War of the World: Twentieth Century Conflict and the Descent of the West (New York: Penguin Press, 2006).

※コメント投稿者のブログIDはブログ作成者のみに通知されます