The following is from Yoshiko Sakurai's official website: https://en.yoshikosakurai.jp/2023/02/02/10408.

JAPAN MUST NOT BE LURED INTO UNWISE COMPROMISE WITH SOUTH KOREA

Relations between Japan and South Korea have long been strained over a host of seemingly endless historical issues. At the forefront now is potential compensation for wartime conscripted Korean workers. On October 30, 2018, the South Korean Supreme Court ordered two Japanese corporations to compensate South Koreans who claim to have been conscripted workers forced to work in Japan during World War II. Needless to say, the corporations refused to comply. On January 12, the South Korean side proposed a possible solution: a South Korean public interest corporation—the Korea-based Foundation for Victims of Forced Mobilization by Imperial Japan (hereafter, the Foundation)—would compensate the plaintiffs as a surrogate for the Japanese corporations.

This proposal is hardly acceptable to Japan, but there are some quarters in Japan centering on the bipartisan Japan-South Korea Parliamentarians' Association that assert that Japan should respond positively to the good faith South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol has shown. The South Korean side is looking forward to "corresponding measures."

What the Korean side has proposed is a legal procedure known as "concurrent debt assumption," which calls for a debtor and an underwriter to "incur a debt jointly and severally without losing the identity of the debt," with a specific financial obligation officially transferred from one party to another. It reflects a notion that the nature of a debt payment remains unchanged no matter who may undertake it. The Korean Supreme Court explains the supposedly "immutable nature of the identity of a debt" in its ruling:

"The plaintiffs' claims for damages are based on the right of the victims of Japan's forced mobilization to claim solatium for the inhumane and unlawful conduct against them on the part of the Japanese corporations that were directly linked to the illegal colonization of the Korean Peninsula and the conduct of the war of invasion by the Japanese government. "The plaintiffs are not claiming a payment of unpaid wages or compensation. Instead, they are claiming solatium for their pain and suffering."

The South Korean Supreme Court judgment, defining Japan's annexation 1910-45 and its subsequent control of the Peninsula as unlawful, is based on the so-called lawless rule theory. The court also defines the treatment of Korean workers by Japanese corporations as inhumane as it characterizes the requested payment as solatium, not unpaid wages. Theoretically, the plaintiffs' claim is valid, because it is a form of payment aimed at atoning for alleged wartime pain and suffering.

Japan implemented the annexation of the Korean Peninsula in accordance with international law. If the Korean Supreme Court wishes to challenge it more than a century later, it must definitely present unequivocal evidence. But the court completely skips that point.

Koreans as Migrant Workers in Japan

Korean plaintiffs who have actually filed lawsuits in South Korea have previously filed similar suits and been dismissed by Japanese courts. The South Korean Supreme Court had this to say about these rulings:

"Accepting the rulings by the Supreme Court of Japan as they are runs counter to the good morals and social order of the Republic of Korea. Therefore, this court has decided that it cannot recognize the validity of the Japanese rulings."

So the South Korean Supreme Court does not recognize the validity of the rulings by its Japanese counterpart because they run "counter to the good morals of the Republic of Korea." This boils down to a battle over the legal systems of Japan and South Korea, and Japan absolutely can not compromise even a little over this matter.

In 1965, Japan and South Korea signed the Japan-Korea Basic Agreement and the "Claims Agreement" (formally, the Agreement Between Japan and the Republic of Korea Concerning the Settlement of Problems in Regard to Property and Claims and Economic Cooperation), winding up 14 years of difficult negotiations. If the South Korean side wishes to deny all the diplomatic efforts both sides made and claim that Japan must pay solatium because Japanese rule over Korea was unlawful and ran counter to the good morals of Korea, then it must give concrete evidence to substantiate its claim. But the ruling by the South Korean Supreme Court makes absolutely no mention of this point.

In the first place, the four former "conscripted workers" for whom the South Korean top court passed the judgment in 2018 were actually not conscripted by the Japanese government but voluntarily came to work in Japan by responding to job offers from Japanese corporations.

In light of the norms of the international community, including Japan, I would think the South Korean court rulings must be seen as invalid because they are based on mistaken facts. But the South Korean side obviously does not care about this crucial matter. They criticize Japan for "coercive wartime mobilization" of all Korean workers in Japan, which actually included a huge number of Koreans who voluntarily found jobs in Japan.

Lee Woo-yeon, a researcher at the Naksungdae Institute of Economic Research in Seoul, has conducted a study on how many Koreans came to work in Japan at the time. The results of his findings must be truly disappointing to those who assert that all Korean workers were coercively mobilized for labor in Japan.

Between 1942 and1944, when recruitment through 'government placement' and mobilization were simultaneously implemented, roughly 1.31 million Koreans came to work in Japan. Of the total, mobilized workers numbered 480,000 (36.4%) and migrant workers 830,000 (63.4%). The total number of Koreans who came to work in Japan was about 2.38 million, including those recruited through government placement and others who had come to Japan before mobilization began. There were 606,000 mobilized workers (25.4%) and 1,774,000 migrant workers (74.6%).

Citing these numbers, Lee points out that Koreans who numbered 2.9 times more than mobilized wartime workers came to work in Japan of their own volition as migrant workers. In other words, more than 1 million Koreans were free to come to Japan to find work. To assert that all of the Koreans who worked in wartime Japan were conscripted workers is a far-fetched argument.

No Time for Compromise

Matters relating to wartime Korean workers in Japan were taken up during the 14-year diplomatic negotiations between Japan and South Korea after the war. While the Japanese government offered to compensate former conscripted workers individually, the South Korean government objected by maintaining that identifying the workers would be impossible. The Japanese side explained that Japanese corporations had kept detailed records concerning the Korean workers they had employed, and proposed that individual compensation be made by the Japanese government on the basis of those lists of names that were available. The South Korean side then requested that Japan pay a lump sum instead, which would include the fund for individual compensation, as the South Korean government considered it its responsibility to settle the matter with the former workers. This is stipulated in Article 1 of the Claims Agreement exchanged with President Park Chung-hee in 1965, which states that Japan is "required to provide South Korea with $300 million in grants and $200 million in loans."

Clause 2 of Article II of the Claims Agreement confirms that issues concerning property and compensation claims for the South Korean people (individuals as well as corporations) "have been settled completely and finally."

Japan's foreign currency reserves at the time stood at barely US$1.8 billion, so it paid South Korea the US$500 million in 10-year installments. It was a heavy financial burden for Tokyo.

Let me return to the South Korean proposal discussed earlier—concurrent debt assumption. On the surface, the Foundation would compensate the plaintiffs. But the proposed settlement would call for Japanese corporations involved in the lawsuits to sign a contract as debtors, stipulating that their debts would be assumed by the Foundation. Japan can hardly accept such an arrangement: signing a document that defines Japanese corporations as real debtors implies legally that Japan, contrary to its assertions, would recognize the South Korean Supreme Court ruling.

In Japan there is a strong opinion among some that Tokyo should make some comprises through "corresponding measures" because President Yoon heads a decent administration whose posture toward

Japan differs widely from the previous left-wing administration of former President Moon Jae-in. These people feel that it is important to not push Yoon into a corner.

But would such a response truly resolve this long-standing issue? Should another left-wing administration like Moon's be born in South Korea going forward, we would be right back where we started. Japan should never give up the fruits of its 14-year diplomatic negotiations with South Korea. We should never give an inch in this legal battle between the Supreme Courts of Japan and South Korea.

The final solution of compensation for conscription workers has been in the hands of the South Korean government since the signing of the 1965 Claims Agreement. Japan's role is simply to stand back and keep a calm eye on developments.

(Translated from "Renaissance Japan" column 1,034 in the February 2, 2023 issue of The Weekly Shincho)

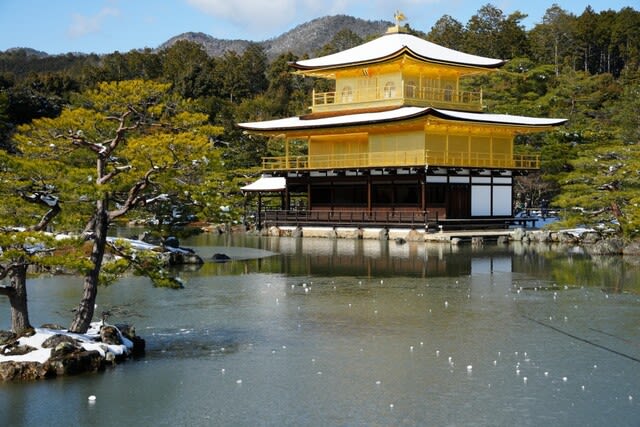

2023/1/26, in Kyoto