日本の高級住宅建築という文化は北海道では、明治初期からの建物で、たとえば清華亭や豊平館のような明治天皇の「御座所」として建てられた建築があるけれど、最初期から寒冷地域の建築として、その「与条件」に対して日本の住文化はどう対応するか、ということが中心軸戦、背骨になっていると思う。

そこでの空間体験がネイティブな人間からすると、この姫路の高級数寄屋建築とは、庭の景観、その先の「借景」環境との内外部の視覚的芸術性が究極的な、きわめる対象だったのだと思える。その日本建築的伝統価値感との根源的相違をいつも感じさせられる。

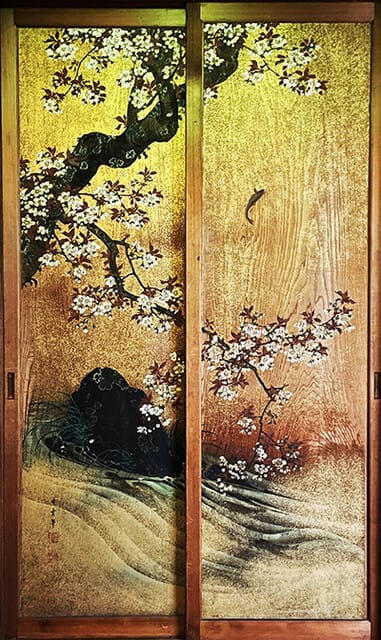

その建築の感受性的な興味対象はつねにそういった視覚的芸術性が最優先されているのだと。それに対して北海道建築は、凶暴なブリザードが室内を暴走し、いたたまれない厳しい冬期自然環境から、室内を保護し、人間居住性を優先させてきた住文化なのだといつも思わされる。この姫路の高級数寄屋住宅での内観空間には、「望景」というわかりやすい眺望最優先の建築動機から、室内装飾障壁画でも風景画一択となっていた。

こうした空間構成の動機からは、四季折々の自然のうつろいが最大関心事として画面が構成されていった。ごく自然に「花鳥風月」がその主要領域とされたのでしょう。「もののあわれ」みたいな心情交流が、最大関心事に昇華されていったものでしょう。

北海道という「異界」で過ごしてきているとはいえ、血族としてはそのルーツを本州以南地域に持っている人間としては、こういった数寄屋の住文化、精神性もいわば血脈としては腑に落ちている。「わかるよなぁ」とは思って受容しているのだけれど、こういった精神世界はいわば「浮ついた世界観」だとも根底的には思い続けている。北海道でこういう花鳥風月を描くとすれば、本州以南地域の建築ではほとんど描かれていない冬の猛吹雪をどう描くか、となる。どうしてもその表現は「箱庭」的な空間性をはるかに超えてしまう。

日本画の後藤純男の作品を富良野の画廊で見ていると、建築自体が正面に雄大な北海道的な山並みに向かって建てられていて、箱庭に自然を写し撮るというような心象ではない。言ってみれば「ポスト花鳥風月」というような表現意欲を感じさせられる。やはりどちらかといえば西洋画のような額縁で囲まれた作品として受け止めることになる。家の中でそうした絵画を鑑賞するとしても、やはり「額縁画」となって壁面に展示される。

この「望景亭」のように建具自体に装画している空間性に、違和感は感じつつも「ああ、いいなぁ」とも本然的には「同期」したいとも感じておりました。見果てぬ夢。

English version⬇

Himeji, Sukiya-style architecture “Bokkei-tei” and wall paintings.

The “Kacho-fu-getsu” worldview is expressed in every place and fixture of the sukiya-style architecture. This is the world of the highest Japanese sensitivity and value. There is no blizzard in winter as the theme of the paintings. ・・・・.

In Hokkaido, the culture of high-class residential architecture dates back to the early Meiji period (1868-1912), with buildings such as the Seikatei and the Toyohirakan, which were built for the Emperor Meiji as his “throne room,” but I think that from the beginning, the central axis and backbone of Japanese residential culture was how to respond to the “given conditions” as architecture in a cold region. The experience of space there is the backbone of the Japanese residential culture.

From the perspective of someone who is a native of Himeji and experienced the space there, it seems to me that the high-class sukiya architecture of Himeji was ultimately about the visual artistry of the garden landscape and the “borrowed landscape” environment inside and out. I am always reminded of the fundamental difference between the traditional values of Japanese architecture and these traditional values.

The sensibility of the architectural interest is always focused on the visual artistry of the building. In contrast, the architecture of Hokkaido has always given priority to human habitability, protecting the interior from the harsh natural environment of winter, when violent blizzards run rampant through the interior and make it unbearable to live in. In the interior space of this high-class sukiya house in Himeji, the motive of the architecture was to give the highest priority to the view, which is easy to understand: “望景”, which means “to look out over the landscape”.

From this motive for spatial composition, the changing nature of the four seasons became the primary concern in the composition of the paintings. The main area of interest was naturally “flowers, birds, wind, and the moon. Emotional exchanges like “the mercy of things” must have been sublimated to the greatest concern.

Although I have spent my life in the “other world” of Hokkaido, as a person whose family roots are in the southern part of Honshu, I understand the culture and spirituality of the sukiya as a bloodline, so to speak. I can understand it and accept it, but at the same time, I continue to think that this kind of spiritual world is a “floating worldview. If I were to depict this kind of flower, bird, wind, and moon in Hokkaido, I would have to find a way to depict the blizzard in winter, which is rarely depicted in architecture in the southern part of Honshu. Inevitably, this expression goes far beyond the “box garden” spatiality.

When I saw the works of Japanese-style painter Sumio Goto at a gallery in Furano, the architecture itself was built facing the majestic Hokkaido-like mountain range in front of it, not the mental image of capturing nature in a box garden. In other words, it is a “post-Kacho-fu-getsu” style of expression. If anything, the works are more like Western-style paintings framed in a frame. When we appreciate such paintings in our homes, they are displayed on the wall as “framed paintings.

I felt a sense of discomfort with the spatiality of the fittings themselves, as in this “Bokkeitei,” but I also felt a sense of “ah, I like it” and naturally wanted to “synchronize” with it. A dream that will never be fulfilled.

※コメント投稿者のブログIDはブログ作成者のみに通知されます