この福島市民家園には、展示館が別に建てられていて、古民家での暮らしぶりや、その民俗のありようについてのさまざまなビジュアル説明が開示されていた。古民家と民俗は当然ながら建築と人間のくらしの関係性、その淡い領域を浮かび上がらせてくれる。わたしたちの先人は古民家での暮らしの中でどのような精神生活を送っていたのか、が見えてくる。

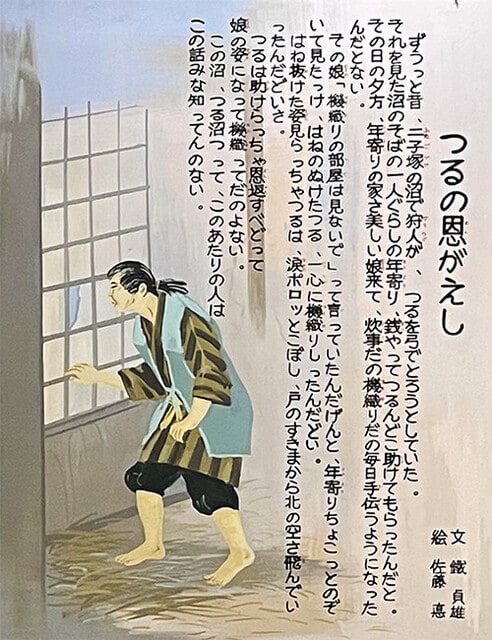

展示で見入っていたのはこの素晴らしい民話譚。内容は方言の話し言葉で読み下していただきたいのだけれど、日本全国どこにもある。Wikiでは以下の要約。

〜一般に「翁が罠にかかった鶴を助け、その鶴が人間の女性に姿を変えて翁とその妻に恩を返す」という筋立てが知られている。類似する話は日本全国で報告されており、文献・伝承によって細部で差違が見られる。 〜

この福島県福島市の郊外・10kmほど離れた地域に「鶴沼」や「二子塚」という地名は具体的に存在しているので、この地域にリアリティを持って語り伝えられてきた伝承と思える。北海道人としては、こういう神代にまで遡るような説話を具体的な地名まで含めて語られると、クラクラとせざるを得ない。

そして古民家での寝物語で、親から子へ連綿と語り継がれてきたのだと想像すると、そのひとびとがリスペクトしていたなにごとかに心を動かされる。地域がこういう説話を共有していることに深く打たれる。とくに方言がそこにメロディとして共鳴までされるとまったく圧倒されてしまう。

この民家園では養蚕文化を伝える古民家も見た。〜【桑の木の中の養蚕民家、湧き上がる暮らしパワー】

この養蚕文化とツルの恩返し伝承は重なるのだろうと容易に想像できる。

個人的な妄想だけれど、養蚕によって蚕というイキモノが農村に貴重な現金収入をもたらす希少な生産手段であり、そこから生産される織物が都市の上流女性を美しく彩ったという生産−流通−消費のプロセスを考えれば、そこにツルという日本列島の自然の中でわかりやすく美を象徴する存在が、物語的に仮託されたことには平仄が合うと感じられる。

寝物語を聞いた女の子たちは、ツルの美しさを想像しながら自分もきっとそういう存在にと、憧れの心理を持ったかも知れないし、男の子たちは「焦がれる」ということの始原をそこに見ていたのではないだろうか。その物語とともに寝に着いただろうたくさんの世代の積層を思わされる。

柳田國男の民俗学からも、柳宗悦の民藝からも、こうした文化を認められなかった北海道人としては、足許を見つめて「あらたな気付き」を探究するしかない、と思う。

English version⬇

The Crane's Benevolence “Local Folklore” Edition / Fukushima City Minka-en - 5

This is a bedtime story of a tale that exists throughout Japan, with the exception of Hokkaido, and gives the specific names of local places. The profundity of the culture is deeply moving. ...

The Fukushima City Minka-en has a separate exhibition hall, which provides a variety of visual explanations of how people lived in old private houses and their folk customs. Naturally, the relationship between old private houses and folklore reveals the faint realm of the relationship between architecture and human life. We can see how our ancestors lived their spiritual lives in old folk houses.

I was fascinated by this wonderful folk tale in the exhibition. The following is a summary from Wiki.

〜The story is generally known as “The old man rescues a crane from a trap, and the crane transforms into a human woman and repays the favor to the old man and his wife. Similar stories have been reported throughout Japan, with differences in details depending on the literature and folklore. 〜The story is told in the suburbs of Fukushima City, Fukushima Prefecture, Japan.

The names “Tsurunuma” and “Futakozuka” exist in the suburbs of Fukushima City, Fukushima Prefecture, about 10 km away, so it seems that this story has been passed down with reality in this area. As a Hokkaido native, I cannot help but feel a little nervous when I hear such tales that date back to the divine era, including the names of specific places.

And when I imagine that these tales were passed down from parents to children in old houses, I am moved by something that these people respected. I am deeply moved by the fact that the local community shares these tales. Especially when the dialect is used as a melody, it is overwhelming.

In this minka garden, I also saw an old house that conveys the culture of sericulture.

It is easy to imagine that this sericultural culture and the tradition of repaying cranes for their kindness overlap.

It is my personal fantasy, but if we consider the production-distribution-consumption process, in which silkworms were a rare means of production that brought valuable cash income to rural villages through sericulture, and the textiles produced from these silkworms beautified urban upper-class women, then it makes sense that the cranes which symbolizes beauty in the natural environment of the Japanese archipelago, was narratively entrusted to the cranes.

The girls who heard the bedtime story may have imagined the beauty of cranes and longed to be one of them, while the boys may have seen the origin of their “longing” in the story. The story reminds us of the layering of many generations who would have arrived at bedtime with the story.

As a Hokkaider who could not recognize this culture from the folklore of Kunio Yanagida or the folk art of Muneyoshi Yanagi, I have no choice but to look at my own feet and search for “new insights”.

※コメント投稿者のブログIDはブログ作成者のみに通知されます