Okinawan Drama; Its Ethnicity and Identity Under Assimilation to Japan

Shoko Yonaha

Introduction

Okinawa was reinstated as a prefecture of Japan quite recently, in 1972; excluding the American Military Occupation (1945-1972), she had been one prefecture of Japan since the abolition of the Kingdom of Ryukyu in 1879[1]. Nonetheless, despite the long history of the islands, it would not be an exaggeration to say that Okinawans are still struggling to find their identity as Okinawans, even if their geo-political identity is defined as being Japanese. This is perhaps because Okinawa was once an independent country whose cultural identity was strongly caught between two dominant countries, i.e., China and Japan. The Kingdom of Ryukyus’ independence had flourished for more than four centuries under the sponsorship of China; Chinese investiture envoys were sent to crown the Ryukyu king 24 times, until the last Sho Dynasty. It lasted even after the unfortunate invasion by the domain of Satsuma (currently Kagoshima Prefecture) in 1609. Secretly hiding its submissive socio-economic stance being exploited from Satsuma, but facing China as her patron-the Kingdom of Ryukyu had to take a double standard on the surface of its policy. However, this did not extend to the performing arts, which in many ways kept the independent culture alive. The purpose of this paper is to discuss how a new form of drama, Okinawa shibai, was born and developed. This will be preceded by a short introduction of the Ryukyuan kumi udui. It also focuses on how Okinawan drama functioned as a device to preserve Okinawans’ past memories and express their ethnic identity under assimilation to Japan.

Even while being a colonial country of Satsuma, and eventually of the Tokugawa Shogunate,[2] the Ryukyu kingdom tried to make its system of policy and idea of cultural identity strongly Ryukyuan. Thus, Ryukyuan aesthetics in the performing arts were born and refined in a politically complex milieu. Tamagusuku Chokun (1687-1734)[3] first created a combined drama called kumi udui[4] and presented it to Chinese envoys in 1719. The presentation of those first five works of kumi udui-“Nidou Tekiuchi” (Revenge of the Two Boys), “Shushin Kane Iri” (Passion and the Bell) which is often compared to the noh play “Dojoji”, “Mekaru-shi” (Master Mekarushi), “Onna-mono-gurui” (The Madwoman), and “Koko no Maki” (Filial Piety) was an epoch-making event for all Ryukyuans, and these works are all well-appreciated for their excellence even today. Kumi udui is a kind of multi-faceted crystal of the performing arts; based on Ryukyu’s local celebratory dance form, choja nu ufusu, and taking some ideas of performance techniques from the Japanese noh, kyogen, and kabuki forms, it is built upon plots taken from original Ryukyuan legends or folk tales. Kumi udui is a composite drama in which chanted dialogue, classic music accompanied by a three-stringed musical instrument called sanshin, other musical instruments such as kutu (koto), kuchoh (Chinese fiddle), fansoh (flute), and tehk (drum), and dances are all combined to make one beautiful harmony. In the complexity of its artistic accomplishment, it is comparable to the highest performing arts anywhere. According to Teruo Yano, a Japanese scholar who has published three books about kumi udui, it is a composite art comprised of poems, music, and dances comparable to an opera of Wagner.[5]

The main characteristics of Chokun’s five kumi udui are, first, the beauty of its lyrics both in dialogues and as chanted by musicians (called jiyute). Second, the rhythm of songs and dialogues mostly consist of 30 syllables, in four lines of eight, eight, eight and six, chanted in tones, which are as crucial as the costumes-colorful and very much stylized. Third, the style of acting has some similarity to noh plays, although generally masks are not used. Four, the plot doesn’t look back, but rather moves only forward to its happy conclusions. Fifth, as it was originally called ukanshin udui (court dances) and appreciated by noble classes and Chinese high-ranking diplomats, those who performed were youth chosen from the nobility. Sixth, the words of those dialogues are a mixture of old classical usages of the Ryukyuan language as well as some old Japanese rhetorical words. Last, kumi udui includes some classical Ryukyu dances, both beautiful and entertaining to audience’s eyes.

Those essential qualities of kumi udui simply symbolize the ethnicity of a very Ryukuan sense with which the kingdom’s ideologies and morals were viewed. For instance, although Confucian ethics (loyalty, filial piety and chastity) form its backbone, folk customs and indigenous beliefs such as Okinawan animism and shamanism, ancestor worship and very strong maternal bonds are also merged into the whole. Above all, ritualistic songs (called omoro) and ryuka (eight-eight-eight-and-six-syllable short poems like Japanese waka or haiku) are taken into the form of kumi udui. To sum up, the birth of kumi udui was significant for the people of Ryukyu, as it has crystallized the core of Ryukyuan ethnicity and identity. Furthermore, it was its performances by the Ryukyu national theatre, which in many ways kept the culture alive.

The birth and development of Okinawan drama (shibai) from 1879 to 1945 under assimilation

When the Kingdom of Ryukyu existed, people of Ryukyus were called Ryukyuan, but after the kingdom was overthrown, Ryukyu-han was changed to Okinawa Prefecture, and the people came to be called Okinawan (or uchinanchu, as opposed to yamatonchu for the Japanese). Since that time, Okinawans have created a Japanese ‘other’ against which to identify themselves.

Sociologist Milton Gordon’s definition[6] of ‘behavioral assimilation’ (also known as ‘acculturation’) fits in the case of Okinawa from 1879 to the Second World War. During this period, Okinawans were obliged to absorb the-supposedly superior-Japanese cultural norms, beliefs, and behavior patterns, and to adapt to them in order to become more Japanese. The process was forceful and it appeared to some extent like a colonization process; Japanese policy didn’t mind eradicating Okinawan culture, languages and beliefs. Japan’s colonial implementation was immediately implemented; the first governor of the newly created Okinawan prefecture successfully spearheaded a new educational system that would plant the Japanese identity into all Okinawans. Language played the main role for achieving this purpose. The Ryukyu languages were looked down upon; students who spoke in Ryukyuan were punished by having a dialect placard (fogen-fuda) hung around their necks in schools.

Later, as we see in many Okinawa plays,[7] which depict subject matters taken from the period of haihan chiken (the abolition of Ryukyu-han and the establishment of Okinawa Prefecture), this historical incident was a difficult change for many Okinawans. Many had to find alternate means of living, especially government officials and others of the samurai-class who served the kingdom. Some of them moved to the villages and taught their songs and dances as well as kumi udui to the villagers. Ironically then, some ‘court’ performing arts were passed down and preserved by the efforts of local villagers; many of them began to be performed in the open-air theaters (ashibina) in the villages.[8] On the other hand, there were some others who stayed in the cities-Shuri and Naha-and held their performances in small open playhouses to earn a living for the first time in the history of Okinawa.

The first performance presented in 1882 was the beginning of commercial theatre in Okinawa. Among those performers, Tamagusuku Seijuu (1868-1945), Tokashiki Shuryo (1880-1953) and Arakaki Shogan (1880-1937) are well known. Though they were showing the court performing arts at first, as time passed by, audiences started to demand new dances and songs, and kyougen or Chogin (a short drama in Okinawan dialect). Audiences wanted their own tastes reflected on the stage. A short time later, Okinawan drama (Okinawa shibai or uchina-shibai) was born. New styles of dances called zou udui (miscellaneous dance) were created, and many commoners became fascinated with the new form of theatre in which they were the main characters along with samurai-class. The first significant opera, which was a 35-minute-long form of shibai, was “Uyanma”(Concubine); it is composed of one scene, in which a zaiban (a samurai sent to Yaeyama Island as its chief bureaucrat), leaves his concubine who served him for two or three years with a child. A boatman takes an initiative and the zaiban accepts the ritual of separation and the couple and the child dance with each other. It is a transitional form between kumi udui and Ryukyu kageki (an opera sung in Ryukyuan language with folk music, adding some classical songs) and called hougen serifu-geki (spoken drama in Ryukyuan, in which subjects are taken from history, legends and real incidents). The way the characters spoke was similar to those of kumi udui but with slight variation, and the dances were accompanied by songs (local folk songs from Yaeyama) and sanshin. The first appearance of “Uyanma”[9] is not recorded, but it is estimated at around 1893.

Later, a large permanent theatre was built and several performing companies in mainland Japan visited Okinawa and performed kabuki and soshi shibai (kiwamono, a form of drama based on real stories). Also, Okinawan actors traveled to Tokyo and Osaka to practice their sense of performance. Cultural exchanges began to take place and Okinawan actors absorbed the essence of both old and modern Japanese style of theatre. Even adapted versions of Shakespeare’s plays, including “Othello”, “Hamlet”, and “The Merchant of Venice” were performed in Okinawan dialect in 1906.[10]

All this happened scarcely 30 years after the Ryukyuan annexation to Japan. Okinawa was even taking in western culture through Japan, and thus Japanese assimilation meant also a sort of westernization. Okinawans performing artists and their art form, Okinawa shibai, were in the process of learning and creating through cultural contact, and it was in this period, in 1907, that the first marvelous Ryukyu kageki (opera) debuted. The three authentic kageki (also called the three greatest Okinawan tragedies) were created from the late Meiji era to Taisyo era and many audiences, especially women, rushed into the theatre. These kageki were “Tumaiaka”(a tragic love story) in 1907, “Okuyama no botan”(a tragic story of a low-caste woman who bore a boy to a samurai, and eventually commits suicide for the sake of her son’s happiness) in 1914, and “Iejima Handuugwa” (about a girl who falls in love with a married man she saves, but who is forsaken and commits suicide) in 1924. These kageki’s lines, songs, and dances cast a spell on the minds of Okinawans, and even now they are repeatedly performed every year. Hougen serifu-geki was also at its peak in 1907; “Nakijin Yuraiki” (a story of a prince of the castle of Nakijin), “Ufu Aragusuku Chyuuden” (a story of one high-ranking samurai’s loyalty and filial piety in the Taisyo era) were also performed around this time. Obviously those kageki and hogen serifu- geki were greatly influenced by kumi udui. Without kumi udui, those great masterpieces of Okinwan shibai wouldn’t have been produced. The details of kumi udui and Okinawa shibai are beyond the scope of this paper, so a lengthy discussion is not needed.

The popularity of Okinawa shibai among the common people was a new phenomenon of this period; accordingly, theatre became the center of media and cultural dissemination. People gathered at the theatre to get a new sense of the era as well as to remind themselves of the history of the kingdom of Ryukyus. Through these drama forms, audiences were unconsciously re-enforcing their cultural identity as Ryukyuans, despite the severe Japanese assimilation policy. Nevertheless, it appears that even among the population, the general trend was toward being Japanese, which, combined with the strict education policy, made great progress towards the termination the Ryukyuan language and the discrediting of Ryukyuan customs.

Because of assimilation policies, it was also true that those who engaged in theatre performance were discriminated against by some establishments and those who highly appreciate Japanization, even if they were welcomed by many audiences. As already noted above, the Rykyuan languages (also referred to as ‘the Okinawan dialects’) were pushed aside as accommodation to Japan was institutionalized through education. However, Okinawa shibai was spoken in Ryukyuan, using a mixture of Shuri and Naha dialects, and had a specific tone of speaking (shibai-kucho) For instance, samurai and commoners’ way of speaking was strictly distinguished. Many plays were colloquially created; for example, there was a style called kuchidate in which a plot was first created and lines were added impromptu by each actor, to the accompaniment of folk music and dances.

What was going on in the society was so complicated that Okinawan performing artists and their audiences were trying, at the same time, to seek and sustain their old cultural memories, and to soak up the new influences of the era. It meant they simultaneously tried to reproduce the heritage their predecessors left behind and recreate new ones; this was done not strictly to sustain the communal cultural memories and assets, but rather to struggle with the big wave of assimilation itself.

In the 1930’s, after a half-century had passed since the abolition of the Kingdom of Ryukyus, Okinawa shibai entered its real golden age; Okinawans came to face-to-face with the tragic history of their country, in a history play written by Yamazato Eikichi (1902-1989). This was a story of the last struggle of the last king and his high- ranking officers. The moment of the fall of the kingdom was presented on stage. Each character’s inner conflict and vision were articulated plainly for all to see. It is said that for one month many Okinawans thronged to see the theater and shed tears. In addition to the newly written history plays, Sangoza (a theater troupe) was established; it was led by Majikina Yuko (1888-1982) and five other actors, Oyadomari Kosyo (1897-1986), Higa Seigi (1893-1976), Hachimine Kiji (1890-1971), Miyagi Nozo (1893-1987), and Shimabukuro Koyu (1893-1987), all highly-valued for their skill. It is said that more than a thousand kageki and quite a few hogen serifu-geki were performed by that time. However, the glory of Sangoza only lasted for 12 years, ending with the destruction of the theatre itself by a U.S air raid in 1944.

It appears likely that, had the pacific war never occured, Okinawan drama and its history would have been far more well-developed and known today. Nevertheless, history shows that the unfortunate results of assimilation to Japan seemed to have been headed to eventual success, despite rampant and cruel discrimination against the Okinawans. This discrimination was made abundantly clear through the actions of Japanese troops stationed there; some Okinawans were killed because of allegations of being foreign spies due to speaking in their Okinawan dialect, and all were treated like secondary Japanese. Okinawans’ identity crisis is perhaps most tragically exemplified by the mass-suicides during the US-Japanese land battles. Countless Okinawans were victimized by the war, and as many as 150.000-one out of every three-Okinawans were killed.

Okinawan shibai from 1945 to the present under assimilation

After the pacific war, Okinawa was occupied by the U.S. military and remained under its control for twenty- seven years. The Japanese emperor’s declaration that he wished Okinawa to be occupied by the U.S. in 1947 became yet another bitter memory for the population. Surprisingly, U.S. General MacArthur declared that the Okinawans are not Japanese and are discriminated against.[11] In effect, MacArthur determined Okinawa’s fate, as it developed into a keystone of the U.S. presence in the Pacific, and remains so to this day. The U.S occupation period was not a detrimental influence on Okinawa shibai, however The U.S. military policy tried to encourage Okinawa traditional values and even supported its development in order to entertain those devastated by the war; shibai troupes were urgently organized and given some official support. Within one year, there existed around forty commercial shibai troupes. Nevertheless, within a decade, Okinawans began to prefer new forms of entertainment like movies and TV shows. Furthermore, political demonstrations asking for a reversion and the reclamation of Japanese citizenship to overcome an unstable political-social status under the U.S. occupation led to the decline of the performance of domestic shibai; being Japanese and having Japanese values were highly appreciated again.

Several Okinawa shibai troupes experienced difficulties and most of them had to cease their theatre activities. Ironically, however, after reversion to Japan in 1972, Okinawans again tried to find their own cultural identity in the performing arts, as can be seen in the Ryukyu dances that have prevailed among women (these were forbidden before the war). Shibai was less accepted but has survived even though not many Okinawans speak Ryukyuan anymore. Nevertheless, the designation of kumi udui as a National Intangible Cultural Treasure in 1972, has preserved the form. Shibai actors had been the main unofficial custodians of kumi udui in the period prior to the war, but this ended when the Okinawan performing arts were divided into five categories: Ryukyu dance, Ryukyu classical music, Ryukyu folk music, Okinawa shibai, and kumi udui. The masters of Okinawa shibai, such as Majikina Yuko, Oyadomari Kosyo, and Miyagi Nozo, stopped practicing shibai performance, and instead opened their private Ryukyu dance kenkyujo (schools).

Ogimi Kotaro (1918-1994) and Makishi Kochu (1903-) are superb Okinawa shibai actors and playwrights who represent the post-World War II era in Okinawa, while Chinen Seishin emerged from the field of shingeki (new theatre). He created a striking play “Jinruikan”(Mad House), and won the 22nd Kishida Drama Award in 1977. The play is about Okinawa and Okinawans in modern history, and discrimination and assimilation in the name of the emperor are cynically observed with a sense of comedy.

Now looking back at more than a century of Okinawa Shibai history, it seems that the fate of kumi udui and Okinawa shibai will be decided in relation to the survival of the Ryukuan language in which they are performed. Today, fortunately, there are a number of young people who not only belong to kumi udui and kageki preservation organizations, but who also make their own theater groups and are interested in performing Okinawa shibai; they are proud to perform as advocates of Okinawan culture.[12] It is certain that they recognize Okinawa shibai as centered in their communal cultural memory.

In 2004, the fourth national theatre “Kokuritu Gekijyo Okinawa” will open in Okinawa. It’s expected that the new national theatre, mainly focused on kumi udui, will bring Okinawans some new aspects for the future of traditional Okinawan performing arts.

Nevertheless, Okinawans as a whole don’t appear to be overly excited about the project. The reason is not clear, but it could be that the theatre is overshadowed by Okinawa’s geopolitical position between Japan and the U.S.; after 27 years of U.S occupation, the reversion to Japan in 1972, and the current continued presence of bases, the role of being the U.S.’s military keystone in the Pacific has never changed, and the Japanese government continues to dominate and influence Okinawa with large amounts of money to keep the bilateral security treaty with the U.S. As some say, for Japan’s dependence on U.S. defense, Okinawa’s self-autonomy and economic independence have been hindered ever since. Obviously, the U.S and Japan are exercising political and economic control and they take advantage by keeping the present situation of Okinawa as it is.

In this socio-political climate, what the national theater can bring to Okinawans is not very clear. The national theatre could be used as a symbol of Japan’s dominant power over Okinawans, or could be used as the strategic center as a measure to win Asians over to Japan’s side; or, as some Okinawans genuinely wished to have a specific theatre for preserving their traditional performing arts, it might serve as they wished as a place for their minds to reside.

Identity crisis and the new sphere of assimilation & possibility of the Okinawan drama

Tatsuhiro Oshiro, a well-known writer and playwright from Okinawa, has created new Okinawan shibai scripts, and recently published a collection of opera plays called “Madama-michi” (2001), and which consist of five new works of kumi udui and a new kageki-certainly a valiant effort to keep Okinawan culture alive. Oshiro, a winner of Japan’s highest literary honor, the Akutagawa prize, for his 1969 novel “Cocktail Party”, was quoted in 2002 in an interview with the Asahi Shimbun newspaper as saying that “Okinawa was once an independent kingdom and now is an internal colony of Japan, and unless some changes occur in both the U.S. and Japan, Okinawa won’t be given any opportunity to change.” He stressed that it is the Japanese government’s policy toward the U.S that should be urgently changed.[13]

Oshiro’s remark is pessimistic regarding the present situation of Okinawa. Yet, in creating five new works of Kumi-Udui, he has worked to maintain Okinawa’s cultural identity. This identity, however, is ambiguous; as Johan Michael Purves points out, “Assimilation to Japan, which had previously been welcomed by the Okinawans themselves, has slowed since the later part of the 1980’s and into the 1990’s, and is now seen to be eroding the foundations of traditional Okinawan culture of ‘Okinawa-ness’.”[14] Shun Medoruma, a 41-year-old writer who won the Akutagawa prize in 1997 says, “Now, we’re neither completely Okinawan nor completely Japanese. We have to find out who we are.”[15]

As is represented by the notions of Oshiro and Medoruma, Okinawans continue to struggle in their quest to find their true identity. Problems such as war, U.S military occupation and Japan’s assimilation have made this difficult over the past century. The future of Okinawa’s identity will also be affected further by globalization, although it remains to be seen whether this influence will be good or bad.

In fact, Okinawa’s socio-political climate could be said to have been very much global from the beginning of the U.S. military occupation in 1945, since Okinawans were completely under the influence of the U.S.’ strategic decisions during this period. Inevitably, Okinawans have had to face America, Japan, and other Asian countries while struggling herself to find her own direction. The best choice in the past was to return to Japan again. Okinawans wished to be protected by Japan’s peaceful constitution. However, since the reversion to Japan, many Okinawans have come to question their decision. One of reasons stemmed from the disillusionment that, even after the occupation, the U.S. military presence has remained essentially the same. As well, as John Purves notes, the idea of assimilation itself has undergone a revision. Okinawans have begun to build their self-confidence and their inferiority complex has decreased. The background of this change in perspectives has several reasons; one of these is the rigidity of the Japanese national identity; another is a gradual economic improvement over the years in Okinawa-although Okinawa’s per capita income levels remain the lowest in Japan. Finally, there is the concept of, as Milton Gordon defines it, cultural pluralism;[16] Okinawans have begun to recognize that Okinawa’s unique cultural norms, traditions and behaviors are not always in conflict with shared common national values, goals and institutions.

Cultural pluralism is occurring in Okinawa. As Okinawans’ cultural differences are seen to be an asset rather than a defect, and as “Okinawa-ness” has begun to gain acceptance throughout the world, Okinawan ethnic music has become very popular in Japan. Certainly, this is one bright side to Okinawa in the beginning of the 21st century. As for Japan, which is supposed to be known as a homogeneous country, it could be a good exercise to take a deeper look at Okinawa’s different cultures and customs in order to meet the requirements of globalization and the multicultural trends of this century.

Not many Okinawans speak in Okinawan dialect anymore. Nonetheless, almost all Okinawan performing arts are written and performed in Ryukyuan; it is in these dialects, and the rhythm of ryuka, that the true sense of ‘Okinawa-ness’ is implanted. No matter what changes time will bring, it is certain that the classic Okinawan performing arts, especially Okinawan kumi udui and shibai, will remain center-stage for Okinawa’s ethnic identity.

References:

[1] King Satto is known for establishing tributary relationships with China in 1372, but the first Sho Dynasty (1406-1469) achieved the political unification of Okinawa in 1422. The second Sho Dynasty (1470-1879) lasted longer than any dynasty and those two Sho Dynasties represent the kingdom of Ryukyu.

[2] The Tokugawa Shogunate was the government of the Tokugawa families who were shoguns, and dominated Japan during the Edo period (1603-1868).

[3] Tamagusuku Chokun was the magistrate in charge of entertainments for the most important events in the Rykyuan royal court, the banquets for the Chinese envoys. He visited Satsuma and Edo several times as a represent of the national mission. It is said that he absorbed Japan’s traditional theatre forms, noh and kabuki, on that occasion.

[4] Now, 75 Kumi Udui(Odori) scripts are found, but not all of them have been performed yet. Along with Tamagusuku Chokun, Heshikiya Chobin (1700-1734), and Tasato Cyocyoku (1714-1775) are well known Kumi Udui writers.

[5] Yano, Teruo, kumiodori wo kiku, Mizuki-shobou, 2003. p.4.

[6] Milton Gordon is an author of Assimilation in American Life: The Role of Race, Religion and National Origins, Oxford Univ. Pr on Demond, 1964. His definition of assimilation is viewed in the web site such as Douglas Massey “What is Assimilation and has it a Spatial Dimension?” (1985) Essay Bank Co.UK. http://www.essaybank.co.uk/free_coursework/290.html

[7] For instance, Shuri Jyo Akewatashi (surrender of shuri castle), Naha-Yumachi-Mukashi-Katagi (old fashioned gentlemen in Naha), Giwan Cyoho no Shi (a death of Giwan Cyoho) by Yamazato Eikichi, Haihan no Ayaame (a wife of samurai in the abolition of the kingdom of Ryukyus) by Ogimi Kotaro, Chinsagu nu Hana (a love story of an outlaw), Aku wo Moteasobumono (a wicked man) by Makishi Kochu, and Yogawariya Yogawariya (a change of the time) by Oshiro Tatsuhiro.

[8] Even today, the village festival called Mura-Udui, or Mura-Shibai is occasionally performed during the harvest season, and usually Kumi-Udui is performed at the end of the programs. Hachigatu-Udui in Tarama island (village) is well known for its specific forms of dances and Kumi-Udui, held for three days every year.

[9] Its way of chanting is called Wandon-Tari-Cho: Wan means I, and it is a style of giving one’s name at the opening of the show.

[10] Most of those Shakespearean plays were adaptation from the production done by Kawakami Otojiro in Japanese in Tokyo or Osaka. Those days, Okinawa theatre, and Kyu-yo theatre had a competition of performing new adapted plays from mainland Japan.

[11] Nomura Hiroya, “Okinawa and Post-colonialism.” P156-158 in Post-Colonialism, ed., by Kan Sanjun, sakuhin-sya, 2001.

[12] Shochiku-kageki-Dan led by Tamaki Mituru, and Gekidan 58 gou sen led by Fukuhara Akira are the main of those theatre groups.

[13] From an interview of Oshiro Tatsuhiro reported in MY TOWN OKINAWA, asahi. com. <http://mytown.asahi.com/okinawa/news01.asp?c=18&kiji=99>

[14] John M.Purves, “Postwar Okinawan Politics and Political culture”, Contemporary Okinawa Website 1955-2002. < > [15] From an interview of Medoruma Shun reported by Tim Larimer, “Identity Crisis,” TIME ASIA July 24.2000 VOL 156 NO.3.

<http://www.niraikanai.wwma.net/pages/base/chap3-1.html>

[15] From an interview of Medoruma Shun reported by Tim Larimer, “Identity Crisis,” TIME ASIA July 24.2000 VOL 156 NO.3. http://www.time.com.time/asia/magazine/2000/0724/japan/okinawa.html.

[16] Milton Gordon, see the web site “Assimilation & Ethic Identity”, Egoldwish.

<http://www.egoldwish.com/aboutus.htm>

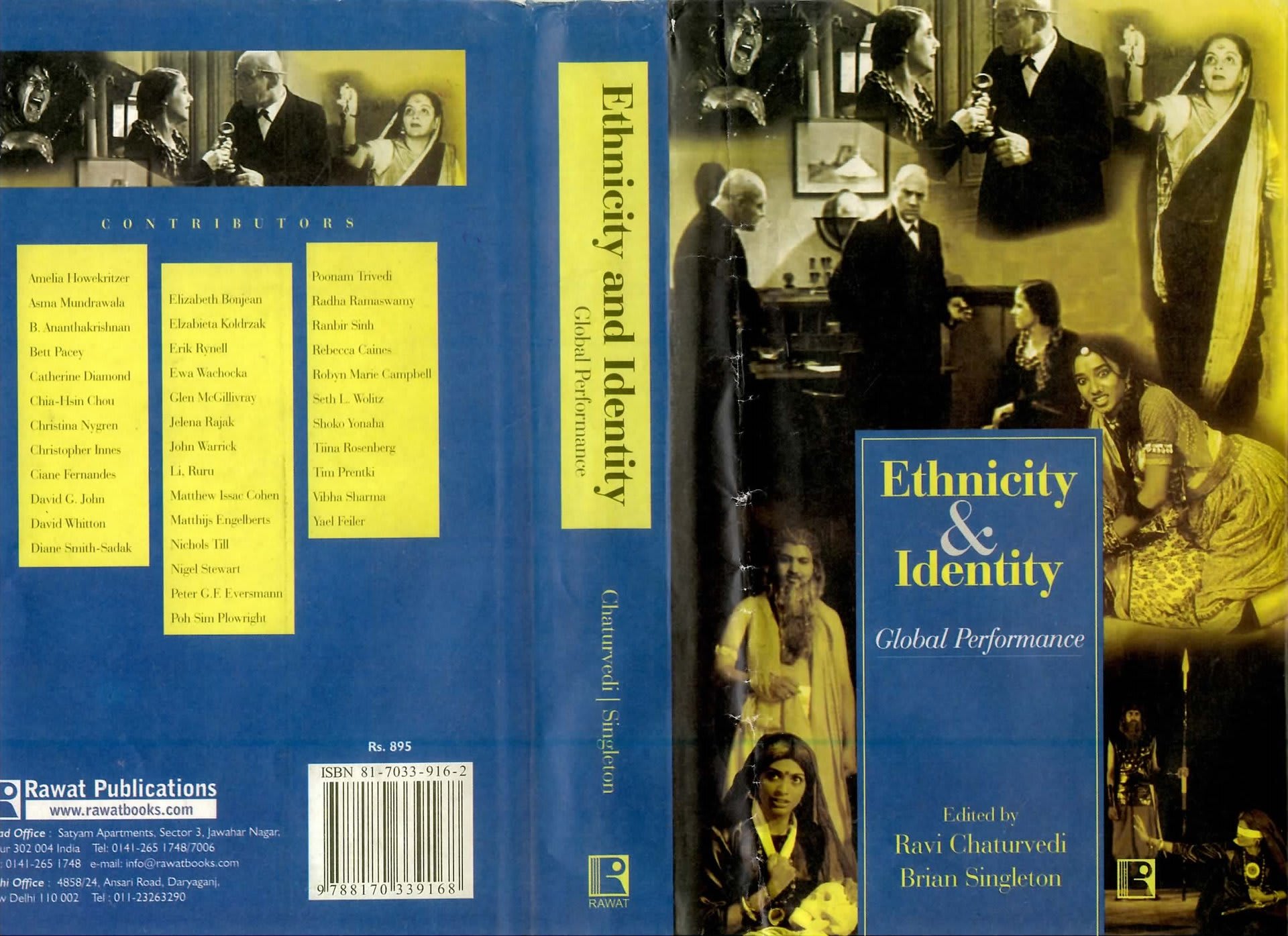

”Ethnicity and Identity Global Performance”

Edited by Ravi Chanturvedi & Brian Singleton , Rawat Publications, 2005

この論稿の中では沖縄方言=Okinawan dialectと使っていますが、それを全部Okinawan languageに訂正する予定ですが、以前の論稿をそのままここに転載します。なぜがHPに掲載しているのですが、一部文字化けして読めないのでこのブログにもってきました。本の方に収録されていますので、もし引用されるのでしたら書物の方を優先されてください!