日本の首相は中国、韓国、そしてアメリカとすら、その外交関係をゼロの位置まで押し戻すもり?

http://kobajun.chips.jp/?p=11857←このサイトです!≪転載≫

エコノミスト 6月3日

何だか生臭い血の匂いが、5月末の東京の外国特派員記者クラブに漂っていました。

将来の日本の首相候補として、これまで名前を売って来た政治界のスターは、歴史的にも政治的にも論議の的となる数々の妄言を放った挙句、厳しい視線を向ける外国特派員たちと向き合わされる羽目に陥りました。

中でも論議の的になったのは、日本維新の会の実質的な党首である橋下徹大阪市長が行った、第二次世界大戦中日本が組織的に行った性的奴隷である従軍慰安婦について、『必要悪』だったとする発言でした。

彼はさらに現代の問題についても言及し、沖縄には日本の米軍基地の75%が集中していますが、そこにいる「熱くなりやすい」兵士たちは、金銭による性欲の処理を行うべきだとも発言したのです。

これまの日本の政治家の常として、橋下氏は頭を下げて自らの発言について謝罪し、その上で外国人特派員との会見に臨むものと予想されていました。

しかし彼はそんなことはしませんでした。

長時間に渡った外国人記者たちとの会見において、橋下氏はアジア各地から200,000人の女性– 一部の研究者たちの試算によれば - を強制的に連行し、従軍慰安婦、つまり性的奴隷として使役したことに、当時の日本政府が関与したという証拠は無いという彼の持論を繰り返しました。

橋下氏は従軍慰安婦となった女性たちに対し一定の配慮を示す一方で、第二次世界大戦に関わった他の国々も、自分たちの過去についても正面から見直す必要があると語っています。

「戦時中の性的問題行動は、何も日本軍に限ったものではありません。」

彼はこう述べ、むしろイギリス軍、アメリカ軍、フランス軍、そしてソ連軍の方が戦場における性的問題行動は多かったと国名を列挙しました。

加えて沖縄の問題に触れた真意は、暴行などの問題を起こした米軍兵士は『心無い少数の例外』であることを強調したかった、その点にあったと語りました。

そして当然ながら、日米の軍事的関係を強化する狙いもあったと語りました。

橋下氏に対する大阪市議会の不信任決議は否決されました。

しかしそれによって、これまでの発言に対する決着がついたと言えるでしょうか?

政治評論家や報道解説者の多くが、橋下氏は自らその政治的経歴を破壊してしまったと見ています。

昨年12月の衆議員議員選挙で1,200万票を獲得し、選挙前の政権与党であった民主党をも上回る得票により、維新の会が国内の第2党に躍り出たことを考えると、今回の橋下氏の一連の発言には改めて驚きを禁じ得ません。

今回の一連の騒ぎは、その正体が何であれ、7月21日の参議院議員総選挙を控えた、安倍信三首相率いる現政権にも重要な教訓をもたらしました。

安倍首相は橋下氏が発言する以前に従軍慰安婦について言及したことがありますが、その見解は橋下氏と同じ立場をとり、関係各国にとってはより一層耳障りなものです。

安倍政権のほとんどの閣僚は、橋下氏よりもさらに強硬な首相と同じ見解を有しています。

例えば橋下氏は慎重に言葉を選びながらも、日本が第二次世界大戦において、植民地獲得のための侵略戦争を行った点については、日本の政治家は認める必要があると語っています。

これに対し安倍政権の閣僚の実に13人が、従軍慰安婦という女性に対する虐待その他の戦争犯罪について、外交上謝罪を行う事を拒絶しているのです。

昨年12月に政権復帰を果たして以来、保守政党の自民党を率いる安倍首相は、橋下氏がはまった罠、すなわち過去の歴史認識に関わる問題には触れないよう、助言を与えられてきました。

しかし安倍首相にはこの問題に距離を置き続けることは無理だったようです。

今年4月、安倍首相は第二次世界大戦当時の日本の問題の中、戦争被害者に対する姿勢に疑問を呈され、『侵略』の定義について問われたことがありました。

安倍首相は根拠のあいまいな言辞を弄したあげく、1995年に当時の村山内閣が示した「日本が植民地支配と侵略によって、多くの国々、とりわけアジア諸国の人々に対して多大の損害と苦痛を与えた」見解を覆す可能性を示唆しました。

5月12日には、自民党の高市早苗政調会長が数百万人のテレビ視聴者に対し、安倍首相が軍国主義当時の日本とその指導者たちの戦争責任を断罪した極東軍事裁判(東京裁判)の判決を認めていないことを明らかにしました。

同じ月には記録的な数の自民党議員団が靖国神社に公式参拝を行いました。

靖国神社には東京裁判によって絞首刑となった戦争犯罪者が合祀されています。

靖国神社への参拝は、軍国主義当時の日本の指導者たちと、その目的に対する無言の支持を表すものです。

極東軍事裁判の判決すら否定するという事になれば、日本は中国、韓国、そしてアメリカとすらその外交関係をゼロの位置まで押し戻すことになります。

その影響は計り知れません。

こうした理由から、安倍政権はその実際の見解を曖昧なままにしておくことに腐心してきました。

政治姿勢を実際とは異なる中立的なものに見せなければならないという計算と、本来の右翼的・国権的立場を露わにしたいとの衝動のはざまで、首相自身が身もだえするような状況が続き、菅官房長官がその都度火消を行うという日々が続きました。

首相が日本は戦争犯罪など犯していないと言えば、官房長官はそんなことは言ってはいないと否定し、首相が戦争犯罪に対する謝罪を撤回すると言えば、これまで通り政府として謝罪するという立場に変わりは無く、1993年の従軍慰安婦の問題の存在を認めた河野談話を撤回するつもりもないと弁明しました。

その安倍首相に今年の始め、政策協力を求められた橋下氏は記者会見で、日本の歴史認識の問題が行き詰ってしまったことを嘆いていました。

「私たちの世代の人間は国民のため、より良い未来を築くためにも、前を向いて進まなければなりません。」

橋下氏はそれまで3時間を費やして20世紀半ばの出来事についての見解を明らかにしたことなど、まるで無かったかのようにこう語ったのです。

http://www.economist.com/blogs/banyan/2013/06/japans-right-wing-politicians

+ – + – + – + – + – + – + – + – + – + – + – + – +

この人たちの発言を聞いていると、どうしても思い出すものがあります。

ナチス・ドイツが行った『絶滅政策』です。

塩野七生さんの『ローマ史』を読むと、ユダヤ人という人々は頑固に自分たち民族のライフスタイルを固守し、その点ではほとんど譲ることが無い人々だということが解ります。

その『異質』さこそが、ナチス・ドイツの『絶滅政策』の原因の一つになったのであろうことは容易に想像がつきます。

他と違う、あるいは多数と異なる意見を持っている、それが攻撃の対象になるのが全体主義の社会です。

ナチス・ドイツの『絶滅政策』の対象になった人々には、ユダヤ人の他、知的障害者、そしてリベラリストや社会主義者などがいました。

日本では『非国民』という言葉が多用されました。

権力構造の最下層に居る人間たちが、些細な落ち度を見つけ、この言葉を浴びせ威嚇する。

威嚇してもひるまないと、特高警察、つまり和製ゲシュタポに密告したり、けしかけたりといった行動に出る。

歴史の針を逆に回し、日本を再びそのような暗い、冷酷な社会に戻す真の目的は何なのか?

その事から決して目を逸らさないようにしないと、この先国民はどんな危険な目に遭わされるか…

杞憂だとお考えですか?

+ – + – + – + – + – + – + – + – + – + – + – + – +

【 英仏海峡の海底から『バトル・オブ・ブリテン』の爆撃機を回収 】

アメリカNBCニュース 6月11日

(写真をクリックして、大きな画像をご覧ください)

大英博物館は、第二次世界大戦中イギリス海峡上で撃墜されたドイツの爆撃機の回収に10日月曜日成功しました。

航空機(その細い胴体のため、「空飛ぶ鉛筆」とあだ名をつけられたドイツ空軍の爆撃機は、70年前の『バトル・オブ・ブリテン』の戦いで、ケント沖で撃墜されました。

回収された機体は錆びてボロボロの状態ですが、これまでに見つかったドイツのドルニエDo 17爆撃機の中では最も状態が良いと見られています。

ひとりのダイバーが、2008年に深さ15メートルの海底に沈んでいたこの機体を発見しました。

機体周辺に遺体の痕跡などはありませんでした。

英国空軍博物館ウェブサイトのブログへの投稿によれば、この爆撃機には4人が乗り組んでいましたが、内2名は捕虜となり、カナダで終戦を迎えました。

爆撃手のハインツ・フーンは墜落時に死亡、通信士のヘルムート・ラインハルトは墜落時の負傷により、後に死亡しました。

Japan's right-wing politicians

http://www.economist.com/blogs/banyan/2013/06/japans-right-wing-politicians←ここから転載です!

Making a hash of history

Jun 3rd 2013, 4:30 by D.M. | TOKYO

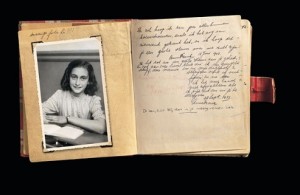

THE scent of blood was in the air at the Tokyo Foreign Correspondents’ Club last week. A rising political star tipped as a candidate for prime minister was facing a hostile crowd of reporters after having uttered a series of controversial bon mots. Most strikingly, Toru Hashimoto (pictured above), the mayor of Osaka and a leader of the right-wing Japan Restoration Party (JRP), said Japan’s organised rape of wartime sex slaves was a necessary evil. Turning to the present day, he also said that “hot-blooded” American soldiers should themselves be using prostitutes more often in Okinawa, which is today home to 75% of the American bases in Japan. In the great tradition of Japanese politics, Mr Hashimoto was expected to bow before his media inquisitors, apologise and move on. He did no such thing.

In that marathon presser, Mr Hashimoto repeated his claim that there is no evidence of the wartime Japanese state’s involvement in herding what some scholars estimate to have been 200,000 Asian women into military brothels. He was aware of the pain suffered by the so-called comfort women, he assured, but said other countries should look squarely at their past too. “Sexual violation in wartime was not unique to the Japanese army,” he said, citing Britain, America, France and Russia for indulging in what he called, rather jarringly, “sex on the battlefield”. His remarks on Okinawa were merely intended to draw attention to the misdeeds of a “heartless minority” of American soldiers, he insisted. And to strengthen Japan’s military alliance with America, naturally.

Mr Hashimoto survived a vote of no-confidence in the Osaka assembly, but the full verdict on the whole performance has yet to emerge—many commentators suspect that Mr Hashimoto has torpedoed his political career. This would be especially extraordinary given his party’s having won a stunning 12m votes in the elections of December 2012, a share that put them ahead of the party of the previous government, the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) as the country’s second-largest. The lessons, whatever they may be, will be of great import to the government of Shinzo Abe, the prime minister, ahead of general elections on July 21st. Mr Abe has previously expressed views on the comfort women that were similar to Mr Hashimoto’s, and even more abrasive. A majority of his government agrees with him and press the point even further than Mr Hashimoto did. Mr Hashimoto was careful to say Japanese politicians should accept that the nation waged colonial wars of aggression in Asia, for instance, while 13 of the lawmakers in Mr Abe’s cabinet reject Japan’s “apology diplomacy” for the abuse of the comfort women and other war crimes.

Since leading the conservative Liberal Democrats (LDP) back to power in December, Mr Abe has been advised to avoid the terrain that ensnared Mr Hashimoto, but it never seemed likely that he could keep himself entirely free of it. In April, he queried the definition of “aggression” in relation to Japan’s colonial wars in Asia—in effect undermining the basis of Tokyo’s relations with its former victims. His semantic quibble had the effect of corroding Japan’s gold-standard apology for its imperial warmongering and atrocities, the 1995 Murayama statement. Indeed, Mr Abe has hinted that he may retract it.

On May 12th, the LDP’s policy chief, Sanae Takaichi, revealed to millions of television viewers that Mr Abe rejects the verdict of the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, which blamed Japan for the war and sentenced its leaders to hang. Then a record number of LDP lawmakers visited the Yasukuni shrine last month, where those hanged leaders were enshrined clandestinely. A pilgrimage to the shrine is taken to imply a tacit endorsement of the wartime leaders and their aims. To reject the verdict of the war trials themselves would mean setting back to zero Japan’s modern relations with China, Korea and even America. The consequences would be profound.

For this reason, Mr Abe’s government has struggled to keep its actual positions opaque. As the prime minister twists and turns, pulled between his political id and the dreadful reality of making them plain, his spokesman, Yoshihide Suga, has spent the month putting out fires. For example: No, says Mr Suga, the prime minister does not deny war crimes; but, Yes, Japan stands by its war apologies. No, Mr Abe does not want to retract the 1993 Kono statement, in which Japan acknowledged its role in rounding up sex slaves.

Mr Hashimoto, who was wooed by Mr Abe earlier this year as a possible political partner, lamented at his press conference that Japan is once again getting bogged down in discussion about the past. “My generation should look ahead and create a better future for our people,” he said. He said this as if he were unaware that he had just spent almost three hours straight talking about the middle of the 20th century.